如何在数字时代更好地学习

简悦花园How to Learn Better in the Digital Age

如何在数字时代更好地学习

Before I got into productivity and performance, I used to spend many hours online ingesting vast troves of digital content. My information diet ranged from inspirational TED talks to specialized podcasts, from blog posts found on Hacker News to ebooks shared on Twitter.\ 在我开始研究工作效率和工作表现之前,我经常花很多时间上网获取大量的数字内容。我的信息饮食范围很广,从鼓舞人心的 TED 演讲到专业播客,从 Hacker News 上的博文到 Twitter 上分享的电子书。

I’m deeply curious, and I gave in to new content as much as I could. What could be the harm?—I thought. I loved spending my time this way. It felt useful, it was fun, and it nurtured my self-image as a “smart guy” — all at the same time. Truly, a learning hack.\ 我深感好奇,于是尽可能地接受新内容。我想,这又何妨呢?我喜欢这样打发时间。我觉得这样做很有用,很有趣,同时还培养了我 "聪明人" 的自我形象。真正的学习黑客。

Turns out I wasn't hacking anything: The learning wasn’t real.\ 事实证明,我并没有黑进任何东西:学习并不真实。

A few months ago, doubts began to creep into my mind about the effectiveness of my habits.\ 几个月前,我开始怀疑自己的习惯是否有效。

While I’d amped up my information consumption, I wasn’t retaining most of it. My memory was behaving like a leaky bucket. Sure, I was spending tens of hours listening to politics on the radio. But when I tried to use any of those points in a conversation, I found that I didn't actually know enough to make a coherent argument. I knew the surrounding context, but the moment I needed to get specific my argument would crumble. Same for many other topics: the more technical they were, the less retention I had.\ 虽然我加大了信息消费的力度,但我并没有保留大部分信息。我的记忆就像一个漏桶。当然,我花了几十个小时听收音机里的政治节目。但当我试图在谈话中使用其中任何一点时,我发现自己实际上并不了解足够的知识来进行连贯的论证。我知道周围的环境,但一旦需要具体说明,我的论点就会崩溃。其他许多话题也是如此:技术性越强,我的记忆力就越差。

Where did all that information go?\ 这些信息都去哪儿了?

The problem lied in how I was seeing learning, and therefore how I was approaching it.\ 问题在于我是如何看待学习的,因此我也是如何对待学习的。

Learning is what turns information consumption into long-lasting knowledge. The two things are different: while information is ephemeral, true knowledge is foundational. If knowledge were a person, information would be its picture.\ 学习是将信息消费转化为持久知识的过程。这两者是不同的:信息是短暂的,而真正的知识是基础性的。如果知识是一个人,那么信息就是它的画像。

It’s easy to think of learning in accretive, cumulative terms: if I stack up enough information, it will eventually turn into knowledge. We tend to judge the world in material terms, and if data were tangible, an indefinitely growing memory might be reasonable to assume. The more information I consume, the more information I store, the information data I can later retrieve. The more business newsletters I’ll read, the more I’ll know business.\ 我们很容易从增量、累积的角度来看待学习:如果我积累了足够多的信息,这些信息最终就会变成知识。我们倾向于用物质来判断世界,如果数据是有形的,那么无限增长的记忆可能是合理的假设。我消费的信息越多,存储的信息就越多,日后能够检索到的信息数据也就越多。我读的商业通讯越多,我对商业的了解就越多。

However, this line of thinking wasn’t really applicable to my case: I was undoubtedly consuming many business newsletters each week, but that wasn’t translating into long-term business knowledge.\ 然而,这种思路并不适用于我的情况:毫无疑问,我每周都会阅读很多商业通讯,但这并没有转化为长期的商业知识。

I spent the last eight months trying to find an answer to this riddle. It took me deep into the topic of meta-learning: How do humans learn? And how can we learn better in the digital information age?\ 在过去的八个月里,我一直在努力寻找这个谜题的答案。这让我深入研究了元学习这一课题:人类是如何学习的?在数字信息时代,我们又该如何更好地学习?

Learning must be effortful

学习必须付出努力

Unfortunately for us, human memory does not resemble storage, and “passive accumulation” isn’t how learning happens.\ 不幸的是,人类的记忆并不像存储,"被动积累" 也不是学习的方式。

The truth is that we retain information only when we put serious effort into the process of learning. The intrinsic effortfulness of learning is not just a byproduct of the core activity, like shortness of breath during running. On the contrary: it’s what actually enables it. The relationship is causal.\ 事实上,我们只有在认真努力学习的过程中才能保留住信息。学习的内在努力并不仅仅是核心活动的副产品,就像跑步时呼吸急促一样。恰恰相反,它才是学习的真正动力。两者之间存在因果关系。

I didn’t find a learning hack to avoid effort because there’s no such thing as easy learning: learning must be effortful in order for it to happen.\ 我没有找到避免付出努力的学习秘诀,因为没有轻松的学习:学习必须付出努力才能实现。

What surprised me the most is that learning is far more grounded in the physical world than I was comfortable admitting.\ 最让我惊讶的是,学习在物理世界中的基础远比我承认的要深厚得多。

The most literal meaning of effort is physical effort (think of weight lifting at the gym). The same holds true with information retention: it works best when the process of assimilating it is physically effortful. Our memory shines when our learning is physical, visceral, and obvious, like the aching in your hands after a morning spent hand-writing.\ 努力的最直观含义就是体力上的付出(想想在健身房举重)。信息保持也是如此:当吸收信息的过程需要付出体力时,效果最好。当我们的学习是身体力行的、直观的和明显的,就像你花了一上午时间手写之后手部的酸痛感一样,我们的记忆力就会大放异彩。

Since they’re passive, easy, and exclusively digital, after this realization all my podcasts, e-books, audiobooks, newsletters, blog posts, videos, live webinars were suddenly deprived of their “learning status”. Instead, they assumed their proper place in my schedule as pure entertainment activities.\ 由于它们是被动的、简单的,而且完全是数字化的,在意识到这一点之后,我的所有播客、电子书、有声读物、新闻通讯、博客文章、视频、网络直播研讨会突然都失去了 "学习地位"。相反,它们在我的日程表中占据了应有的位置,成为纯粹的娱乐活动。

The fact of the matter is that digital products make it uniquely easy to trick yourself into thinking that you’re learning when you are actually being entertained.\ 事实上,数字产品能让人轻而易举地欺骗自己,以为自己在学习,其实是在娱乐。

What I still didn’t know was why our mind works like this. Is this just the current state of digital learning and teaching, or there’s actually a margin for easy learning to be found somewhere?\ 我仍然不知道的是,我们的思维为什么会这样。这仅仅是数字化学习和教学的现状,还是在某个地方确实存在轻松学习的余地?

The neurology of learning

学习神经学

I’m no expert in medicine, let alone neurology, but I did want to roughly understand what happens when we — as humans — create knowledge. Luckily I didn’t need profound medical expertise to get the gist of the matter.\ 我不是医学专家,更不是神经病学专家,但我确实想大致了解我们人类创造知识时会发生什么。幸运的是,我并不需要高深的医学知识就能了解事情的要点。

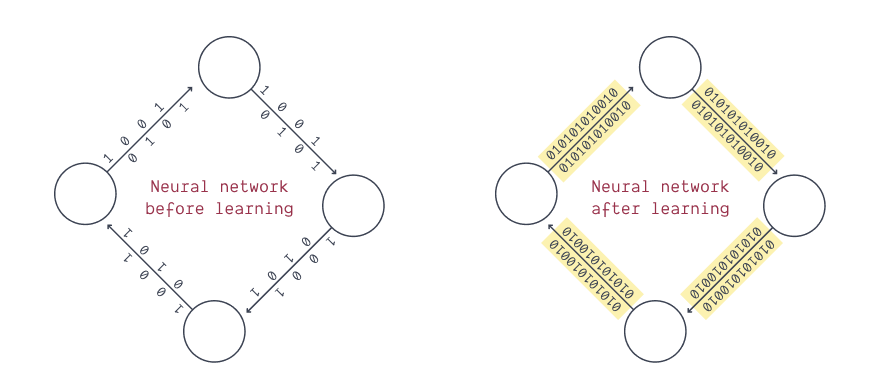

Our brain is made of a web of interconnected neurons. The links between these neurons are called axons: long, slender projections of nerve fibers that transmit electrical impulses.\ 我们的大脑由相互连接的神经元组成。这些神经元之间的联系被称为轴突:细长的神经纤维突起,可以传递电脉冲。

Around these axons, there’s an insulating membrane called myelin. It covers many neuronal axons and facilitates the propagation of electrical signals along neuronal circuits. The more myelin around an axon, the stronger and more connected the signal transmission will be.\ 在这些轴突周围,有一层叫做髓鞘的绝缘膜。它覆盖着许多神经元轴突,有助于电信号沿着神经元回路传播。轴突周围的髓鞘越多,信号传输的强度和连接性就越强。

Myelin is to neural transmissions as oxygen is to fire. It allows rapid information transfer over long distances, and it greatly increases the speed of propagation of electric signals in our brain.\ 髓鞘之于神经传输,就像氧气之于火焰。它能使信息长距离快速传递,并大大提高电信号在大脑中的传播速度。

See it as water flowing through a pipe with dynamic, changing capacity. Pipes with greater capacity can move more water, more quickly than a small pipe or a slow drip. The more myelin supporting a neural connection, the easier it is to use that connection — and thus to use the skill or remember the topic associated with that connection\ 将其视为水流通过容量动态变化的管道。容量大的管道能比小管道或缓慢滴水的管道流出更多的水,速度更快。支持神经连接的髓鞘越多,就越容易使用该连接,从而使用技能或记住与该连接相关的主题

A key aspect of myelin is that it’s highly dynamic. It’s an integral component of our brain plasticity. So the question becomes: how is myelin generated, and why?\ 髓鞘的一个重要方面是它具有高度动态性。它是大脑可塑性不可或缺的组成部分。那么问题来了:髓鞘是如何生成的?

When we come across a new topic, new regions of the brain start activating. The more we use those new regions, the more myelin is synthesized, the easier that topic (or activity) gets.\ 当我们遇到一个新话题时,大脑的新区域就会开始激活。我们越多地使用这些新区域,髓鞘的合成就越多,该主题(或活动)就越容易。

We all know the old saying practice makes perfect. The more we use a certain region of our brain, the more our brain "prioritizes"and"hones" it. That is what leads to myelin: activity induces myelination, which leads to increased strength of connectivity and efficiency along those very neurons. It’s a self-reinforcing process.\ 我们都知道 "熟能生巧" 这句老话。我们使用大脑的某个区域越多,大脑就会越 "优先" 和 "磨练" 它。这就是形成髓鞘的原因:活动诱导髓鞘化,从而提高这些神经元的连接强度和效率。这是一个自我强化的过程。

In other words, it compounds.\ 换句话说,它是一种化合物。

See now why it’s so hard to learn? To learn anything we must make active use of unexplored regions of our brain before they're ready. It's, quite literally, getting out of the comfort zone. The more we use them, the more they get better. Learning is structurally hard.\ 现在明白为什么学习如此困难了吧?要学习任何知识,我们必须在大脑尚未准备好之前,积极利用大脑中尚未开发的区域。从字面上看,这就是走出舒适区。我们使用得越多,它们就会变得越好。学习在结构上是困难的。

The truly mesmerizing thing about myelination is that it is correlated with active use of motor neurons. It looks like human cognition is fundamentally grounded in sensory-motor processes: we retain information better when we associate some physical activity to it. The general intuition is that movement provides additional cues we can use to retrieve knowledge.\ 髓鞘化的真正迷人之处在于,它与运动神经元的积极使用相关。看起来,人类的认知从根本上是建立在感官运动过程的基础上的:当我们将一些身体活动与信息联系起来时,我们就能更好地保留信息。一般的直觉是,运动提供了额外的线索,我们可以利用它来检索知识。

We can see this effect happening when we take notes. A larger corpus of research is suggesting that taking notes physically — that is, by hand-writing them — is far more effective than using a laptop. Keyboarding does not provide tactile feedback to the brain that the contact between pencil and paper does: this contact, this raw feedback, is the key to creating the neurocircuitry in the hand-brain complex, that evidence shows supports memory and retention.\ 我们在记笔记时就能看到这种效果。更多的研究表明,用手写的方式记笔记要比用笔记本电脑有效得多。键盘输入无法向大脑提供触觉反馈,而铅笔和纸张之间的接触却能提供触觉反馈:这种接触,这种原始的反馈,是在手脑复合体中建立神经回路的关键,有证据表明,这种神经回路有助于记忆和保持。

All of this means we need to radically reassess digital learning. We haven’t evolved to store information by passively watching Masterclass videos: that’s just not how our minds work.\ 所有这些都意味着我们需要从根本上重新评估数字化学习。我们并没有进化到通过被动观看大师班视频来存储信息的地步:这不是我们的思维方式。

However, the other side of this coin is that we’re living in times of unprecedented information surplus. This is an opportunity that we should learn to seize.\ 然而,硬币的另一面是,我们正生活在一个前所未有的信息过剩时代。我们应该学会抓住这个机遇。

Creative learning in a digital world

数字世界中的创造性学习

The best way to describe my information diet before discovering that effort is instrumental to learning would be edutainment.\ 用寓教于乐来形容我在发现努力有助于学习之前的信息饮食最恰当不过了。

Edutainment mixes education topics with entertainment methodologies. Even if edutainment optimizes for passive attention instead of effortful engagement (the opposite of learning), it’s not just “mere fun.” Deleting Twitter and unsubscribing from newsletters, as suggested by Deep Work advocates like Cal Newport, can actually end up preventing learning.\ 寓教于乐将教育主题与娱乐方法相结合。即使寓教于乐优化的是被动的注意力而不是努力的参与(学习的反面),它也不仅仅是 "单纯的娱乐"。正如卡尔 - 纽波特(Cal Newport)等 "深度工作" 倡导者所建议的那样,删除推特和取消订阅新闻邮件实际上会阻碍学习。

I see edutainment as preparation for learning: it’s a powerful explorative tool that can provide ideas and motivation to learn. And yet, it’s also not learning itself, in the same way as buying running shoes is not running.\ 我认为寓教于乐是为学习做准备:它是一种强大的探索工具,可以提供学习的思路和动力。然而,它本身也不是学习,就像买跑鞋不是跑步一样。

Within this framework, “mindless” browsing online can be transformed into scouting for learning opportunities. It’s yet another searching problem where it’s key to balance the exploration of new opportunities with the commitment to the existing ones — a topic I wrote about at length in another essay. It’s about balancing the time spent “scouting” for interesting topics online with the offline effort needed for long-term retention and integration.\ 在这个框架内,"漫不经心" 的网上浏览可以转变为寻找学习机会。这是另一个搜索问题,关键是要在探索新机会与坚持现有机会之间取得平衡 -- 我在另一篇文章中详细论述过这个话题。这涉及到如何平衡在线 "搜寻" 有趣主题所花费的时间与长期保留和整合所需的线下努力。

Pragmatically, I solved this trade-off with a powerful tool: a learning inbox.\ 务实地说,我用一个强大的工具解决了这一权衡问题:学习收件箱。

A learning inbox is a to-do list for stuff I’d like to actually learn. I picked up the idea from Andy Matuschak — legendary ed-tech expert —, who used a similar concept as a tool for capturing possibly-useful references. The learning inbox is a system that forces me to be mindful about what content is learning, and what is at the end of the day just entertainment.\ 学习收件箱是我想真正学习的东西的待办事项列表。我从安迪 - 马图沙克(Andy Matuschak)-- 传奇的教育技术专家 -- 那里学到了这个想法,他用类似的概念作为一种工具来捕捉可能有用的参考资料。学习收件箱是一个系统,它迫使我注意哪些内容是学习,哪些内容最终只是娱乐。

Everything interesting I find on my way is sent to my learning inbox and from there gets triaged, be it a paper, an online essay, a blog post, a YouTube video, or a podcast. When an item ends up in there, there are three things that can happen: I either decide to actively engage with it, to file for future interest, or just trash it. Active engagement is exactly what it sounds like: I need to take effortful action to consume the content in the list, otherwise I automatically bucket it as entertainment.\ 无论是论文、在线论文、博文、YouTube 视频还是播客,我在路上发现的所有有趣的东西都会被发送到我的学习收件箱,并在那里进行分拣。当一项内容出现在收件箱中时,会有三种情况发生:我要么决定积极处理它,要么将它归档以备后用,要么直接将它扔掉。积极处理就是听起来的样子:我需要采取努力的行动来消费列表中的内容,否则我就会自动把它当作娱乐来处理。

In other words, I need to do something with it. To create something. Write a blog post about it, use it in a new project, test it on the field, teach it at a meetup. That’s why I speak at many conferences: it’s a learning tool.\ 换句话说,我需要用它做点什么。创造一些东西。写一篇关于它的博文,在新项目中使用它,在现场测试它,在聚会上教授它。这就是我在许多会议上发言的原因:这是一种学习工具。

In GTD fashion, permanence in this list is temporary. It's a release valve, not a procrastination tool.\ 按照 GTD 的方式,这份清单的永久性是暂时的。它是一个释放阀门,而不是拖延工具。

For example, I recently came across a tweet during the last Election day mentioning a video about computational democracy. I’m extremely interested in the intersection between politics and data, so I sent the link to my learning inbox (a task on Things 3) – and then promptly forgot about it.\ 例如,最近在大选日期间,我在推特上看到了一段关于计算民主的视频。我对政治和数据之间的交集非常感兴趣,于是我把链接发到了我的学习收件箱里(这是 "第 3 件事" 中的一项任务),然后很快就忘了这件事。

A few days later, during one of my ritual learning sprints, I took out my notepad and watched the whole video while taking handwritten notes. I then reviewed and transcribed what I had jotted down to an evergreen digital note in my personal knowledge base. The whole process took twice as long as watching the video, and it’s not even a done deal: I would still need some kind of experimentation, tinkering, iteration, application in different contexts, and generally something more hands-on than just note-taking to significantly solidify my knowledge on the topic. That’s what learning takes.\ 几天后,在一次例行的学习冲刺中,我拿出记事本,一边手写笔记,一边观看了整个视频。然后,我复习并将记下的内容转录到个人知识库中的常青数字笔记中。整个过程花的时间是看视频的两倍,而且还没有完成:我还需要做一些实验、修补、迭代、在不同环境中应用,总之需要比记笔记更多的实践,才能大大巩固我对这个主题的认识。这就是学习的过程。

The process takes a lot of time and effort, which means it’s not something I can afford to do with every piece of content I find online. Most of the time I trash the links I find, upon further review. Sometimes they end up in my learning wish list.\ 这个过程需要花费大量的时间和精力,这意味着我不可能对在网上找到的每一条内容都这样做。大多数情况下,我都会在进一步查看后将找到的链接扔掉。有时,它们会出现在我的学习愿望列表中。

The core idea is trying my best to not kid myself: when my engagement with a piece of content is active and effortful then it’s learning, when it’s passive it’s entertainment. When I create I learn. When I consume I just relax.\ 我的核心理念是尽力不自欺欺人:当我积极努力地参与一项内容时,它就是学习;当我被动地参与时,它就是娱乐。当我创作时,我学习。当我消费时,我只是放松。

Bottom line: we need to engage with what we encounter if we wish to absorb it long term. In a smartphone-driven society, real engagement, beyond the share or like or retweet, got fundamentally difficult – or, put another way, not engaging got fundamentally easier. Passive browsing is addictive: the whole information supply chain is optimized for time spent in-app, not for retention and proactivity.\ 一句话:如果我们希望长期吸收我们所遇到的东西,我们就需要参与其中。在智能手机驱动的社会中,除了分享、点赞或转发之外,真正的参与从根本上变得困难,或者换一种说法,不参与从根本上变得更容易。被动浏览会让人上瘾:整个信息供应链都是针对在应用中花费的时间而优化的,而不是针对保留和主动性。

Luckily, the other side of the coin is that finding new topics and new reasons to learn got dramatically easier, with such an abundance of content and stimuli.\ 幸运的是,硬币的另一面是,有了如此丰富的内容和刺激,寻找新的主题和新的学习理由变得更加容易。

We just need to be proactive with how we engage with all of the streams of content available to us. To go out and build, write, talk, teach, explain, create — effortful actions, that lead to meaningful growth.\ 我们只需要积极主动地参与到所有可用的内容流中。去建设、写作、谈话、教学、解释、创造 -- 这些努力的行动会带来有意义的成长。

That's for sure what I’m going to do.\ 我肯定会这么做的。

Generated by RSStT. The copyright belongs to the original author.