Wikipedia

en.wikipedia.org

Jump to navigation Jump to search

For other uses, see PH (disambiguation).

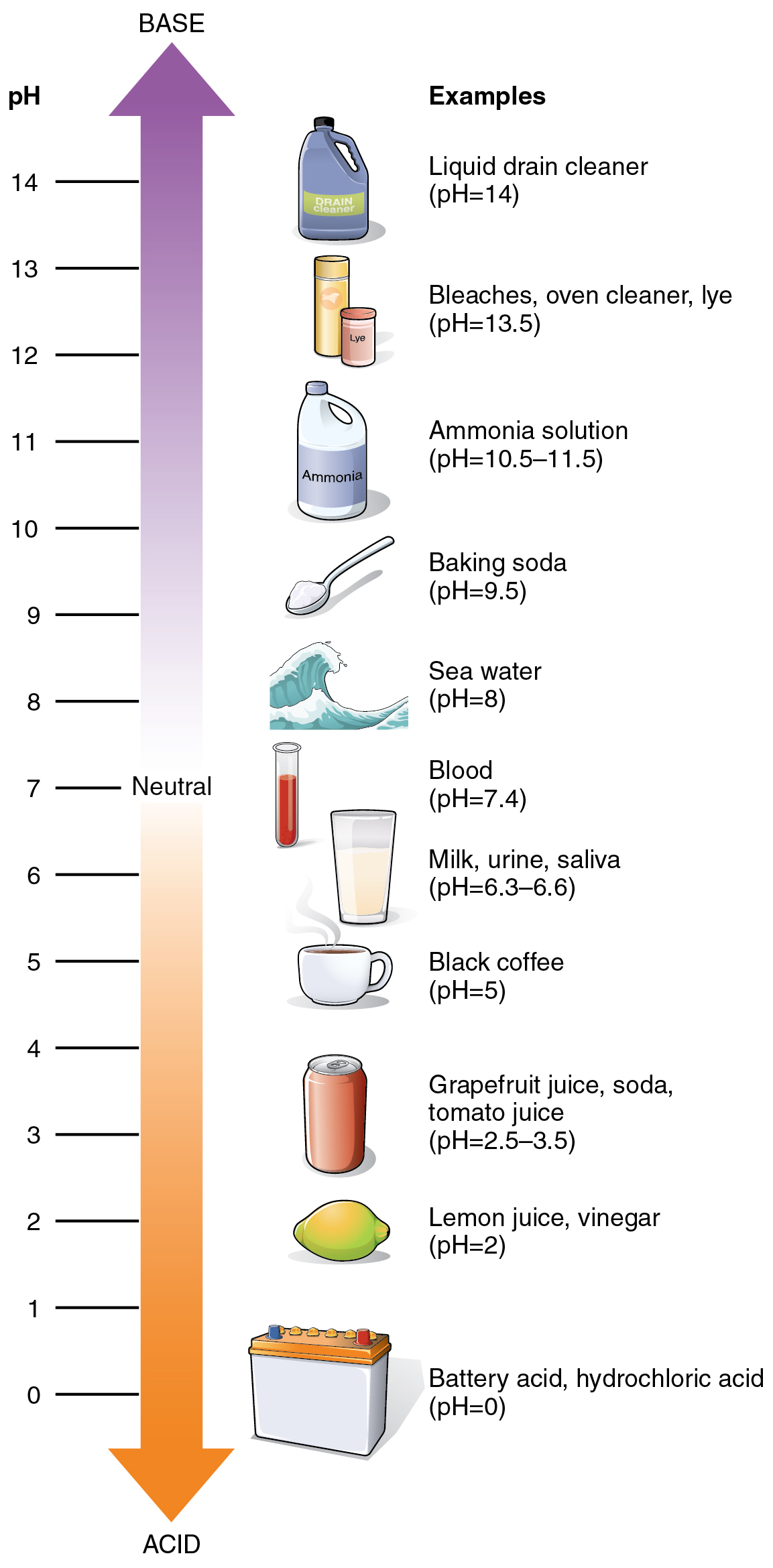

In chemistry, pH () is a logarithmic scale used to specify the acidity or basicity of an aqueous solution. It is approximately the negative of the base 10 logarithm of the molar concentration, measured in units of moles per liter, of hydrogen ions. More precisely it is the negative of the base 10 logarithm of the activity of the hydrogen ion.[1] Solutions with a pH less than 7 are acidic and solutions with a pH greater than 7 are basic. Pure water is neutral, at pH 7 (25 °C), being neither an acid nor a base. Contrary to popular belief, the pH value can be less than 0 or greater than 14 for very strong acids and bases respectively.[2]

Measurements of pH are important in agronomy, medicine, chemistry, water treatment, and many other applications.

The pH scale is traceable to a set of standard solutions whose pH is established by international agreement.[3] Primary pH standard values are determined using a concentration cell with transference, by measuring the potential difference between a hydrogen electrode and a standard electrode such as the silver chloride electrode. The pH of aqueous solutions can be measured with a glass electrode and a pH meter, or an indicator.

There are three current theories used to describe acid–base reactions: Arrhenius, Bronsted-Lowry and Lewis when determining pH.

Contents

History

The concept of pH was first introduced by the Danish chemist Søren Peder Lauritz Sørensen at the Carlsberg Laboratory in 1909[4] and revised to the modern pH in 1924 to accommodate definitions and measurements in terms of electrochemical cells. In the first papers, the notation had the "H" as a subscript to the lowercase "p", as so: pH.

The exact meaning of the "p" in "pH" is disputed, but according to the Carlsberg Foundation, pH stands for "power of hydrogen".[5] It has also been suggested that the "p" stands for the German Potenz[not in citation given] (meaning "power"), others refer to French puissance (also meaning "power", based on the fact that the Carlsberg Laboratory was French-speaking). Another suggestion is that the "p" stands for the Latin terms pondus hydrogenii (quantity of hydrogen), potentia hydrogenii (capacity of hydrogen), or potential hydrogen. It is also suggested that Sørensen used the letters "p" and "q" (commonly paired letters in mathematics) simply to label the test solution (p) and the reference solution (q).[6] Currently in chemistry, the p stands for "decimal cologarithm of", and is also used in the term pKa, used for acid dissociation constants.[7]

Bacteriologist Alice C. Evans, famed for her work's influence on dairying and food safety, credited William Mansfield Clark and colleagues (of whom she was one) with developing pH measuring methods in the 1910s, which had a wide influence on laboratory and industrial use thereafter. In her memoir, she does not mention how much, or how little, Clark and colleagues knew about Sørensen's work a few years prior.[8]:10 She said:

In these studies [of bacterial metabolism] Dr. Clark's attention was directed to the effect of acid on the growth of bacteria. He found that it is the intensity of the acid in terms of hydrogen-ion concentration that affects their growth. But existing methods of measuring acidity determined the quantity, not the intensity, of the acid. Next, with his collaborators, Dr. Clark developed accurate methods for measuring hydrogen-ion concentration. These methods replaced the inaccurate titration method of determining acid content in use in biologic laboratories throughout the world. Also they were found to be applicable in many industrial and other processes in which they came into wide usage.[8]:10

The first electronic method for measuring pH was invented by Arnold Orville Beckman, a professor at California Institute of Technology in 1934.[9] It was in response to local citrus grower Sunkist that wanted a better method for quickly testing the pH of lemons they were picking from their nearby orchards.[10]

Definition and measurement

pH

pH is defined as the decimal logarithm of the reciprocal of the hydrogen ion activity, aH+, in a solution.[3]

pH = − log 10 ( a H + ) = log 10 ( 1 a H + ) {\displaystyle {\ce {pH}}=-\log _{10}(a_{{\ce {H+}}})=\log _{10}\left({\frac {1}{a_{{\ce {H+}}}}}\right)}

For example, a solution with a hydrogen ion activity of 5×10−6 = 1/(2×105) (at that level essentially the number of moles of hydrogen ions per liter of solution) has a pH of log10(2×105) = 5.3. For a commonplace example based on the facts that the masses of a mole of water, a mole of hydrogen ions, and a mole of hydroxide ions are respectively 18 g, 1 g, and 17 g, a quantity of 107 moles of pure (pH 7) water, or 180 tonnes (18×107 g), contains close to 1 g of dissociated hydrogen ions (or rather 19 g of H3O+ hydronium ions) and 17 g of hydroxide ions.

Note that pH depends on temperature. For instance at 0 °C the pH of pure water is 7.47. At 25 °C it's 7.00, and at 100 °C it's 6.14.

This definition was adopted because ion-selective electrodes, which are used to measure pH, respond to activity. Ideally, electrode potential, E, follows the Nernst equation, which, for the hydrogen ion can be written as

E = E 0 + R T F ln ( a H + ) = E 0 − 2.303 R T F pH {\displaystyle E=E^{0}+{\frac {RT}{F}}\ln(a_{{\ce {H+}}})=E^{0}-{\frac {2.303RT}{F}}{\ce {pH}}}

where E is a measured potential, E0 is the standard electrode potential, R is the gas constant, T is the temperature in kelvins, F is the Faraday constant. For H+ number of electrons transferred is one. It follows that electrode potential is proportional to pH when pH is defined in terms of activity. Precise measurement of pH is presented in International Standard ISO 31-8 as follows:[11] A galvanic cell is set up to measure the electromotive force (e.m.f.) between a reference electrode and an electrode sensitive to the hydrogen ion activity when they are both immersed in the same aqueous solution. The reference electrode may be a silver chloride electrode or a calomel electrode. The hydrogen-ion selective electrode is a standard hydrogen electrode.

Reference electrode | concentrated solution of KCl || test solution | H2 | Pt[

Firstly, the cell is filled with a solution of known hydrogen ion activity and the emf, ES, is measured. Then the emf, EX, of the same cell containing the solution of unknown pH is measured.

pH ( X ) = pH ( S ) + E S − E X z {\displaystyle {\ce {pH(X)}}={\ce {pH(S)}}+{\frac {E_{{\ce {S}}}-E_{{\ce {X}}}}{z}}}

The difference between the two measured emf values is proportional to pH. This method of calibration avoids the need to know the standard electrode potential. The proportionality constant, 1/z is ideally equal to 1 2.303 R T / F {\displaystyle {\frac {1}{2.303RT/F}}\ }

the "Nernstian slope".

To apply this process in practice, a glass electrode is used rather than the cumbersome hydrogen electrode. A combined glass electrode has an in-built reference electrode. It is calibrated against buffer solutions of known hydrogen ion activity. IUPAC has proposed the use of a set of buffer solutions of known H+ activity.[3] Two or more buffer solutions are used in order to accommodate the fact that the "slope" may differ slightly from ideal. To implement this approach to calibration, the electrode is first immersed in a standard solution and the reading on a pH meter is adjusted to be equal to the standard buffer's value. The reading from a second standard buffer solution is then adjusted, using the "slope" control, to be equal to the pH for that solution. Further details, are given in the IUPAC recommendations.[3] When more than two buffer solutions are used the electrode is calibrated by fitting observed pH values to a straight line with respect to standard buffer values. Commercial standard buffer solutions usually come with information on the value at 25 °C and a correction factor to be applied for other temperatures.

The pH scale is logarithmic and therefore pH is a dimensionless quantity.

p[H]

This was the original definition of Sørensen,[5] which was superseded in favor of pH in 1909. However, it is possible to measure the concentration of hydrogen ions directly, if the electrode is calibrated in terms of hydrogen ion concentrations. One way to do this, which has been used extensively, is to titrate a solution of known concentration of a strong acid with a solution of known concentration of strong alkaline in the presence of a relatively high concentration of background electrolyte. Since the concentrations of acid and alkaline are known, it is easy to calculate the concentration of hydrogen ions so that the measured potential can be correlated with concentrations. The calibration is usually carried out using a Gran plot.[12] The calibration yields a value for the standard electrode potential, E0, and a slope factor, f, so that the Nernst equation in the form

E = E 0 + f 2.303 R T F log [ H + ] {\displaystyle E=E^{0}+f{\frac {2.303RT}{F}}\log[{\ce {H+}}]}

can be used to derive hydrogen ion concentrations from experimental measurements of E. The slope factor, f, is usually slightly less than one. A slope factor of less than 0.95 indicates that the electrode is not functioning correctly. The presence of background electrolyte ensures that the hydrogen ion activity coefficient is effectively constant during the titration. As it is constant, its value can be set to one by defining the standard state as being the solution containing the background electrolyte. Thus, the effect of using this procedure is to make activity equal to the numerical value of concentration.

The glass electrode (and other ion selective electrodes) should be calibrated in a medium similar to the one being investigated. For instance, if one wishes to measure the pH of a seawater sample, the electrode should be calibrated in a solution resembling seawater in its chemical composition, as detailed below.

The difference between p[H] and pH is quite small. It has been stated[13] that pH = p[H] + 0.04. It is common practice to use the term "pH" for both types of measurement.

pH indicators

Main article: Universal indicator

Indicators may be used to measure pH, by making use of the fact that their color changes with pH. Visual comparison of the color of a test solution with a standard color chart provides a means to measure pH accurate to the nearest whole number. More precise measurements are possible if the color is measured spectrophotometrically, using a colorimeter or spectrophotometer. Universal indicator consists of a mixture of indicators such that there is a continuous color change from about pH 2 to pH 10. Universal indicator paper is made from absorbent paper that has been impregnated with universal indicator. Another method of measuring pH is using an electronic pH meter.

pOH

pOH is sometimes used as a measure of the concentration of hydroxide ions. OH−. pOH values are derived from pH measurements. The concentration of hydroxide ions in water is related to the concentration of hydrogen ions by

[ OH − ] = K W [ H + ] {\displaystyle [{\ce {OH^-}}]={\frac {K_{{\ce {W}}}}{[{\ce {H^+}}]}}}

where KW is the self-ionisation constant of water. Taking logarithms

pOH = p K W − pH {\displaystyle {\ce {pOH}}={\ce {p}}K_{{\ce {W}}}-{\ce {pH}}}

So, at room temperature, pOH ≈ 14 − pH. However this relationship is not strictly valid in other circumstances, such as in measurements of soil alkalinity.

Extremes of pH

Measurement of pH below about 2.5 (ca. 0.003 mol dm−3 acid) and above about 10.5 (ca. 0.0003 mol dm−3 alkaline) requires special procedures because, when using the glass electrode, the Nernst law breaks down under those conditions. Various factors contribute to this. It cannot be assumed that liquid junction potentials are independent of pH.[14] Also, extreme pH implies that the solution is concentrated, so electrode potentials are affected by ionic strength variation. At high pH the glass electrode may be affected by "alkaline error", because the electrode becomes sensitive to the concentration of cations such as Na+ and K+ in the solution.[15] Specially constructed electrodes are available which partly overcome these problems.

Runoff from mines or mine tailings can produce some very low pH values.[16]

Non-aqueous solutions

Hydrogen ion concentrations (activities) can be measured in non-aqueous solvents. pH values based on these measurements belong to a different scale from aqueous pH values, because activities relate to different standard states. Hydrogen ion activity, aH+, can be defined[17][18] as:

a H + = exp ( μ H + − μ H + ⊖ R T ) {\displaystyle a_{{\ce {H+}}}=\exp \left({\frac {\mu _{{\ce {H+}}}-\mu _{{\ce {H+}}}^{\ominus }}{RT}}\right)}

where μH+ is the chemical potential of the hydrogen ion, μ H + ⊖ {\displaystyle \mu _{{\ce {H+}}}^{\ominus }}

is its chemical potential in the chosen standard state, R is the gas constant and T is the thermodynamic temperature. Therefore, pH values on the different scales cannot be compared directly due to different solvated proton ions such as lyonium ions, requiring an intersolvent scale which involves the transfer activity coefficient of hydronium/lyonium ion.

pH is an example of an acidity function. Other acidity functions can be defined. For example, the Hammett acidity function, H0, has been developed in connection with superacids.

Unified absolute pH scale

The concept of "unified pH scale" has been developed on the basis of the absolute chemical potential of the proton. This model uses the Lewis acid–base definition. This scale applies to liquids, gases and even solids.[19] In 2010, a new "unified absolute pH scale" has been proposed that would allow various pH ranges across different solutions to use a common proton reference standard.[20]

Applications

Pure water is neutral. When an acid is dissolved in water, the pH will be less than 7 (25 °C). When a base, or alkali, is dissolved in water, the pH will be greater than 7. A solution of a strong acid, such as hydrochloric acid, at concentration 1 mol dm−3 has a pH of 0. A solution of a strong alkali, such as sodium hydroxide, at concentration 1 mol dm−3, has a pH of 14. Thus, measured pH values will lie mostly in the range 0 to 14, though negative pH values and values above 14 are entirely possible. Since pH is a logarithmic scale, a difference of one pH unit is equivalent to a tenfold difference in hydrogen ion concentration.

The pH of neutrality is not exactly 7 (25 °C), although this is a good approximation in most cases. Neutrality is defined as the condition where [H+] = [OH−] (or the activities are equal). Since self-ionization of water holds the product of these concentration [H+]×[OH−] = Kw, it can be seen that at neutrality [H+] = [OH−] = √Kw, or pH = pKw/2. pKw is approximately 14 but depends on ionic strength and temperature, and so the pH of neutrality does also. Pure water and a solution of NaCl in pure water are both neutral, since dissociation of water produces equal numbers of both ions. However the pH of the neutral NaCl solution will be slightly different from that of neutral pure water because the hydrogen and hydroxide ions' activity is dependent on ionic strength, so Kw varies with ionic strength.

If pure water is exposed to air it becomes mildly acidic. This is because water absorbs carbon dioxide from the air, which is then slowly converted into bicarbonate and hydrogen ions (essentially creating carbonic acid).

CO 2 + H 2 O ↽ − − ⇀ HCO 3 − + H + {\displaystyle {\ce {CO2 + H2O <=> HCO3^- + H+}}}

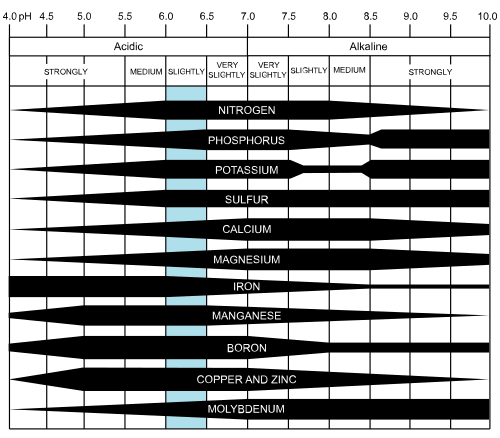

pH in soil

Classification of soil pH ranges

The United States Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service, formerly Soil Conservation Service classifies soil pH ranges as follows: [21]

Denomination pH range Ultra acidic < 3.5 Extremely acidic 3.5–4.4 Very strongly acidic 4.5–5.0 Strongly acidic 5.1–5.5 Moderately acidic 5.6–6.0 Slightly acidic 6.1–6.5 Neutral 6.6–7.3 Slightly alkaline 7.4–7.8 Moderately alkaline 7.9–8.4 Strongly alkaline 8.5–9.0 Very strongly alkaline > 9.0

pH in nature

pH-dependent plant pigments that can be used as pH indicators occur in many plants, including hibiscus, red cabbage (anthocyanin) and red wine. The juice of citrus fruits is acidic mainly because it contains citric acid. Other carboxylic acids occur in many living systems. For example, lactic acid is produced by muscle activity. The state of protonation of phosphate derivatives, such as ATP, is pH-dependent. The functioning of the oxygen-transport enzyme hemoglobin is affected by pH in a process known as the Root effect.

Seawater

See also: Ocean acidification

The pH of seawater is typically limited to a range between 7.5 and 8.4.[22] It plays an important role in the ocean's carbon cycle, and there is evidence of ongoing ocean acidification caused by carbon dioxide emissions.[23] However, pH measurement is complicated by the chemical properties of seawater, and several distinct pH scales exist in chemical oceanography.[24]

As part of its operational definition of the pH scale, the IUPAC defines a series of buffer solutions across a range of pH values (often denoted with NBS or NIST designation). These solutions have a relatively low ionic strength (≈0.1) compared to that of seawater (≈0.7), and, as a consequence, are not recommended for use in characterizing the pH of seawater, since the ionic strength differences cause changes in electrode potential. To resolve this problem, an alternative series of buffers based on artificial seawater was developed.[25] This new series resolves the problem of ionic strength differences between samples and the buffers, and the new pH scale is referred to as the 'total scale', often denoted as pHT. The total scale was defined using a medium containing sulfate ions. These ions experience protonation, H+ + SO2−

4 ⇌ HSO−

4, such that the total scale includes the effect of both protons (free hydrogen ions) and hydrogen sulfate ions:

[H+]T = [H+]F + [HSO−

4]

An alternative scale, the 'free scale', often denoted 'pHF', omits this consideration and focuses solely on [H+]F, in principle making it a simpler representation of hydrogen ion concentration. Only [H+]T can be determined,[26] therefore [H+]F must be estimated using the [SO2−

4] and the stability constant of HSO−

4, K*

S:

[H+]F = [H+]T − [HSO−

4] = [H+]T ( 1 + [SO2−

4] / K*

S )−1

However, it is difficult to estimate K*

S in seawater, limiting the utility of the otherwise more straightforward free scale.

Another scale, known as the 'seawater scale', often denoted 'pHSWS', takes account of a further protonation relationship between hydrogen ions and fluoride ions, H+ + F− ⇌ HF. Resulting in the following expression for [H+]SWS:

[H+]SWS = [H+]F + [HSO−

4] + [HF]

However, the advantage of considering this additional complexity is dependent upon the abundance of fluoride in the medium. In seawater, for instance, sulfate ions occur at much greater concentrations (>400 times) than those of fluoride. As a consequence, for most practical purposes, the difference between the total and seawater scales is very small.

The following three equations summarise the three scales of pH:

pHF = − log [H+]F pHT = − log ( [H+]F + [HSO−

4] ) = − log [H+]T pHSWS = − log ( [H+]F + [HSO−

4] + [HF] ) = − log [H+]SWS

In practical terms, the three seawater pH scales differ in their values by up to 0.12 pH units, differences that are much larger than the accuracy of pH measurements typically required, in particular, in relation to the ocean's carbonate system.[24] Since it omits consideration of sulfate and fluoride ions, the free scale is significantly different from both the total and seawater scales. Because of the relative unimportance of the fluoride ion, the total and seawater scales differ only very slightly.

Living systems

The pH of different cellular compartments, body fluids, and organs is usually tightly regulated in a process called acid-base homeostasis. The most common disorder in acid-base homeostasis is acidosis, which means an acid overload in the body, generally defined by pH falling below 7.35. Alkalosis is the opposite condition, with blood pH being excessively high.

The pH of blood is usually slightly basic with a value of pH 7.365. This value is often referred to as physiological pH in biology and medicine. Plaque can create a local acidic environment that can result in tooth decay by demineralization. Enzymes and other proteins have an optimum pH range and can become inactivated or denatured outside this range.

Calculations of pH

The calculation of the pH of a solution containing acids and/or bases is an example of a chemical speciation calculation, that is, a mathematical procedure for calculating the concentrations of all chemical species that are present in the solution. The complexity of the procedure depends on the nature of the solution. For strong acids and bases no calculations are necessary except in extreme situations. The pH of a solution containing a weak acid requires the solution of a quadratic equation. The pH of a solution containing a weak base may require the solution of a cubic equation. The general case requires the solution of a set of non-linear simultaneous equations.

A complicating factor is that water itself is a weak acid and a weak base (see amphoterism). It dissociates according to the equilibrium

2 H 2 O ↽ − − ⇀ H 3 O + ( aq ) + OH − ( aq ) {\displaystyle {\ce {2H2O <=> H3O+ (aq) + OH^-(aq)}}}

with a dissociation constant, Kw defined as

K w = [ H + ] [ OH − ] {\displaystyle K_{w}={\ce {[H+][OH^-]}}}

where [H+] stands for the concentration of the aqueous hydronium ion and [OH−] represents the concentration of the hydroxide ion. This equilibrium needs to be taken into account at high pH and when the solute concentration is extremely low.

Strong acids and bases

Strong acids and bases are compounds that, for practical purposes, are completely dissociated in water. Under normal circumstances this means that the concentration of hydrogen ions in acidic solution can be taken to be equal to the concentration of the acid. The pH is then equal to minus the logarithm of the concentration value. Hydrochloric acid (HCl) is an example of a strong acid. The pH of a 0.01M solution of HCl is equal to −log10(0.01), that is, pH = 2. Sodium hydroxide, NaOH, is an example of a strong base. The p[OH] value of a 0.01M solution of NaOH is equal to −log10(0.01), that is, p[OH] = 2. From the definition of p[OH] above, this means that the pH is equal to about 12. For solutions of sodium hydroxide at higher concentrations the self-ionization equilibrium must be taken into account.

Self-ionization must also be considered when concentrations are extremely low. Consider, for example, a solution of hydrochloric acid at a concentration of 5×10−8M. The simple procedure given above would suggest that it has a pH of 7.3. This is clearly wrong as an acid solution should have a pH of less than 7. Treating the system as a mixture of hydrochloric acid and the amphoteric substance water, a pH of 6.89 results.[30]

Weak acids and bases

A weak acid or the conjugate acid of a weak base can be treated using the same formalism.

{ Acid : HA ↽ − − ⇀ H + + A − Base : HA + ↽ − − ⇀ H + + A {\displaystyle {\begin{cases}{\ce {Acid:}}&{\ce {HA <=> H+ + A^-}}\\{\ce {Base:}}&{\ce {HA+ <=> H+ + A}}\end{cases}}}

First, an acid dissociation constant is defined as follows. Electrical charges are omitted from subsequent equations for the sake of generality

K a = [ H ] [ A ] [ HA ] {\displaystyle K_{a}={\frac {{\ce {[H] [A]}}}{{\ce {[HA]}}}}}

and its value is assumed to have been determined by experiment. This being so, there are three unknown concentrations, [HA], [H+] and [A−] to determine by calculation. Two additional equations are needed. One way to provide them is to apply the law of mass conservation in terms of the two "reagents" H and A.

C A = [ A ] + [ HA ] {\displaystyle C_{{\ce {A}}}={\ce {[A]}}+{\ce {[HA]}}}

C H = [ H ] + [ HA ] {\displaystyle C_{{\ce {H}}}={\ce {[H]}}+{\ce {[HA]}}}

C stands for analytical concentration. In some texts, one mass balance equation is replaced by an equation of charge balance. This is satisfactory for simple cases like this one, but is more difficult to apply to more complicated cases as those below. Together with the equation defining Ka, there are now three equations in three unknowns. When an acid is dissolved in water CA = CH = Ca, the concentration of the acid, so [A] = [H]. After some further algebraic manipulation an equation in the hydrogen ion concentration may be obtained.

[ H ] 2 + K a [ H ] − K a C a = 0 {\displaystyle [{\ce {H}}]^{2}+K_{a}[{\ce {H}}]-K_{a}C_{a}=0}

Solution of this quadratic equation gives the hydrogen ion concentration and hence p[H] or, more loosely, pH. This procedure is illustrated in an ICE table which can also be used to calculate the pH when some additional (strong) acid or alkaline has been added to the system, that is, when CA ≠ CH.

For example, what is the pH of a 0.01M solution of benzoic acid, pKa = 4.19?

- Step 1: K a = 10 − 4.19 = 6.46 × 10 − 5 {\displaystyle K_{a}=10^{-4.19}=6.46\times 10^{-5}}

- Step 2: Set up the quadratic equation. [ H ] 2 + 6.46 × 10 − 5 [ H ] − 6.46 × 10 − 7 = 0 {\displaystyle [{\ce {H}}]^{2}+6.46\times 10^{-5}[{\ce {H}}]-6.46\times 10^{-7}=0}

- Step 3: Solve the quadratic equation. [ H + ] = 7.74 × 10 − 4 ; p H = 3.11 {\displaystyle [{\ce {H+}}]=7.74\times 10^{-4};\quad \mathrm {pH} =3.11}

For alkaline solutions an additional term is added to the mass-balance equation for hydrogen. Since addition of hydroxide reduces the hydrogen ion concentration, and the hydroxide ion concentration is constrained by the self-ionization equilibrium to be equal to K w [ H + ] {\displaystyle {\frac {K_{w}}{{\ce {[H+]}}}}}

C H = [ H ] + [ HA ] − K w [ H ] {\displaystyle C_{\ce {H}}={\frac {[{\ce {H}}]+[{\ce {HA}}]-K_{w}}{\ce {[H]}}}}

In this case the resulting equation in [H] is a cubic equation.

General method

Some systems, such as with polyprotic acids, are amenable to spreadsheet calculations.[31] With three or more reagents or when many complexes are formed with general formulae such as ApBqHr,the following general method can be used to calculate the pH of a solution. For example, with three reagents, each equilibrium is characterized by an equilibrium constant, β.

[ A p B q H r ] = β p q r [ A ] p [ B ] q [ H ] r {\displaystyle [{\ce {A}}_{p}{\ce {B}}_{q}{\ce {H}}_{r}]=\beta _{pqr}[{\ce {A}}]^{p}[{\ce {B}}]^{q}[{\ce {H}}]^{r}}

Next, write down the mass-balance equations for each reagent:

C A = [ A ] + Σ p β p q r [ A ] p [ B ] q [ H ] r C B = [ B ] + Σ q β p q r [ A ] p [ B ] q [ H ] r C H = [ H ] + Σ r β p q r [ A ] p [ B ] q [ H ] r − K w [ H ] − 1 {\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}C_{\ce {A}}&=[{\ce {A}}]+\Sigma p\beta _{pqr}[{\ce {A}}]^{p}[{\ce {B}}]^{q}[{\ce {H}}]^{r}\\C_{\ce {B}}&=[{\ce {B}}]+\Sigma q\beta _{pqr}[{\ce {A}}]^{p}[{\ce {B}}]^{q}[{\ce {H}}]^{r}\\C_{\ce {H}}&=[{\ce {H}}]+\Sigma r\beta _{pqr}[{\ce {A}}]^{p}[{\ce {B}}]^{q}[{\ce {H}}]^{r}-K_{w}[{\ce {H}}]^{-1}\end{aligned}}}

Note that there are no approximations involved in these equations, except that each stability constant is defined as a quotient of concentrations, not activities. Much more complicated expressions are required if activities are to be used.

There are 3 non-linear simultaneous equations in the three unknowns, [A], [B] and [H]. Because the equations are non-linear, and because concentrations may range over many powers of 10, the solution of these equations is not straightforward. However, many computer programs are available which can be used to perform these calculations. There may be more than three reagents. The calculation of hydrogen ion concentrations, using this formalism, is a key element in the determination of equilibrium constants by potentiometric titration.

See also

References

Source en.wikipedia.org