Ukraine

Ukraine ([Ukrainian]: Україна, Ukraina; Ukrainian pronunciation: [ukrɑˈjinɑ]), [sometimes called the Ukraine],[9] is a [sovereign state] in [Eastern Europe],[10] [bordered] by [Russia] to the east and northeast; [Belarus] to the northwest; [Poland], [Hungary], and [Slovakia] to the west; [Romania] and [Moldova] to the southwest; and the [Black Sea] and [Sea of Azov] to the south and southeast, respectively. Ukraine is currently in a [territorial dispute] with Russia over the [Crimean Peninsula], which [Russia annexed in 2014][11] but which Ukraine and most of the international community recognise as Ukrainian. Including Crimea, Ukraine has an area of 603,628 km2 (233,062 sq mi),[12] making it the largest country entirely within [Europe] and the [46th] largest country in the world. Excluding Crimea, Ukraine has a population of about 42.5 million, making it the [32nd] most populous country in the world.[13]

The territory of modern Ukraine has been inhabited since 32,000 BC. During the [Middle Ages], the area was a key centre of East Slavic culture, with the powerful state of [Kievan Rus'] forming the basis of Ukrainian identity. Following its fragmentation in the 13th century, the territory was contested, ruled and divided by a variety of powers, including [Lithuania], [Poland], [Austria-Hungary], the [Ottoman Empire] and [Russia]. A [Cossack republic] emerged and prospered during the 17th and 18th centuries, but its territory was eventually split between [Poland] and the [Russian Empire], and finally merged fully into the Russian-dominated Soviet Union in the late 1940s.

During the 20th century three periods of independence occurred. The first of these periods occurred briefly during and immediately after the German occupation near the end of [World War I] and the second occurred, also briefly, and also during German occupation, during [World War II]. However, both of these first two earlier periods would eventually see Ukraine's territories consolidated back into a [Soviet republic] within the [USSR]. The third period of independence began in 1991, when Ukraine gained its independence from the Soviet Union in the aftermath of [its dissolution] at the end of the [Cold War]. Ukraine has maintained its independence as a sovereign state ever since. Before its independence, Ukraine was typically referred to in English as "The Ukraine", but sources since then have moved to drop "the" from the name of Ukraine in all uses.[14]

Following its independence, Ukraine declared itself a [neutral state].[15] Nonetheless it formed a limited military partnership with the Russian Federation and other [CIS countries] and a [partnership with NATO] in 1994. In the 2000s, the government began leaning towards NATO, and a deeper cooperation with the alliance was set by the NATO-Ukraine Action Plan signed in 2002. It was later agreed that the question of joining NATO should be answered by a national referendum at some point in the future.[16] Former [President] [Viktor Yanukovych] considered the current level of co-operation between [Ukraine and NATO] sufficient,[17] and was against Ukraine joining NATO.[18] In 2013, after the government of President Yanukovych had decided to suspend the [Ukraine-European Union Association Agreement] and seek closer economic ties with Russia, a several-months-long wave of demonstrations and protests known as the [Euromaidan] began, which later escalated into the [2014 Ukrainian revolution] that led to the overthrow of President Yanukovych and his cabinet and the establishment of a new government. These events formed the background for the [annexation of Crimea by Russia] in March 2014, and the [War in Donbass] in April 2014. On 1 January 2016, Ukraine applied the economic part of the [Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area] with the European Union.[19]

Ukraine has long been a global [breadbasket] because of its extensive, fertile farmlands and is one of the world's largest [grain exporters].[20][21] The diversified [economy of Ukraine] includes a large [heavy industry] sector, particularly in aerospace and industrial equipment.

Ukraine is a [unitary republic] under a [semi-presidential system] with [separate powers]: [legislative], [executive] and [judicial] branches. Its capital and largest city is [Kiev]. Taking into account reserves and paramilitary personnel,[22] Ukraine maintains the second-largest [military] in Europe after that of Russia. The country is home to 42.5 million people (excluding [Crimea]),[13] 77.8 percent of whom are [Ukrainians] "by ethnicity", followed by a sizeable minority of [Russians] (17.3 percent) as well as [Georgians], [Romanians]/[Moldovans], [Belarusians], [Crimean Tatars], [Bulgarians] and [Hungarians]. [Ukrainian] is the [official language] and its alphabet is [Cyrillic]. The dominant religions in the country are [Eastern Orthodoxy] and [Greek Catholicism], which have strongly influenced [Ukrainian architecture], [literature] and [music]. It is a member of the [United Nations] since its founding, the [Council of Europe], [OSCE], [GUAM], and one of the founding states of the [Commonwealth of Independent States] (CIS).

Etymology

There are different hypotheses as to the etymology of the [name Ukraine]. According to the older and most widespread hypothesis, it means "borderland",[23] while more recently some linguistic studies claim a different meaning: "homeland" or "region, country".[24]

"The Ukraine" was once the usual form in English,[25] but since the [Declaration of Independence of Ukraine], "the Ukraine" has become much less common in the [English-speaking world], and style-guides largely recommend not using the definite [article].[14][26] "The Ukraine" now implies disregard for the country's sovereignty, according to U.S. ambassador [William Taylor].[27] The Ukrainian position is that the usage of "'The Ukraine' is incorrect both grammatically and politically."[9]

History

Early history

[Neanderthal] settlement in Ukraine is seen in the Molodova archaeological sites (43,000–45,000 BC) which include a mammoth bone dwelling.[28][29] The territory is also considered to be the likely location for the human [domestication of the horse].[30][31][32][33]

Modern human settlement in Ukraine and its vicinity dates back to 32,000 BC, with evidence of the [Gravettian culture] in the [Crimean Mountains].[34][35] By 4,500 BC, the [Neolithic] [Cucuteni-Trypillian Culture] flourished in a wide area that included parts of modern Ukraine including [Trypillia] and the entire [Dnieper]-[Dniester] region. During the [Iron Age], the land was inhabited by [Cimmerians], [Scythians], and [Sarmatians].[36] Between 700 BC and 200 BC it was part of the Scythian Kingdom, or [Scythia].[37]

Beginning in the sixth century BC, colonies of [Ancient Greece], [Ancient Rome] and the [Byzantine Empire], such as [Tyras], [Olbia] and [Chersonesus], were founded on the northeastern shore of the [Black Sea]. These colonies thrived well into the 6th century AD. The [Goths] stayed in the area but came under the sway of the [Huns] from the 370s AD. In the 7th century AD, the territory of eastern Ukraine was the centre of [Old Great Bulgaria]. At the end of the century, the majority of Bulgar tribes migrated in different directions, and the [Khazars] took over much of the land.[citation needed]

Antes people

In the 5th and 6th centuries, the [Antes] were located in the territory of what is now Ukraine. The Antes were the ancestors of [Ukrainians]: [White Croats], [Severians], [Polans], [Drevlyans], [Dulebes], [Ulichians], and [Tiverians]. Migrations from Ukraine throughout the [Balkans] established many [Southern Slavic] nations. Northern migrations, reaching almost to the [Ilmen Lakes], led to the emergence of the [Ilmen Slavs], [Krivichs], and [Radimichs], the groups ancestral to the [Russians]. After an Avar raid in 602 and the collapse of the Antes Union, most of these peoples survived as separate tribes until the beginning of the second millennium.[citation needed]

Golden Age of Kiev

Kievan Rus' was founded by the [Rus' people], who came from Scandinavia across [Ladoga] and settled in Kiev around 880 AD. Kievan Rus' included the central, western and northern part of modern Ukraine, [Belarus], far eastern strip of Poland and the western part of present-day Russia. According to the Primary Chronicle the Rus' elite initially consisted of [Varangians] from [Scandinavia].[citation needed]

During the 10th and 11th centuries, it became the largest and most powerful state in Europe.[38] It laid the foundation for the national identity of Ukrainians and Russians.[39] [Kiev], the capital of modern Ukraine, became the most important city of the Rus'.

The Varangians later assimilated into the Slavic population and became part of the first Rus' dynasty, the [Rurik Dynasty].[39] Kievan Rus' was composed of several [principalities] ruled by the interrelated Rurikid knyazes ("princes"), who often fought each other for possession of Kiev.[citation needed]

The Golden Age of Kievan Rus' began with the reign of [Vladimir the Great] (980–1015), who [turned Rus' toward Byzantine Christianity]. During the reign of his son, [Yaroslav the Wise] (1019–1054), Kievan Rus' reached the zenith of its cultural development and military power.[39] The state soon fragmented as the relative importance of regional powers rose again. After a final resurgence under the rule of [Vladimir II Monomakh] (1113–1125) and his son [Mstislav] (1125–1132), Kievan Rus' finally disintegrated into separate principalities following Mstislav's death.[citation needed]

The 13th century [Mongol invasion] devastated Kievan Rus'. Kiev was totally [destroyed in 1240].[40] On today's Ukrainian territory, the principalities of [Halych] and [Volodymyr-Volynskyi] arose, and were merged into the state of [Galicia-Volhynia].[41]

[Danylo Romanovych] (Daniel I of Galicia or Danylo Halytskyi) son of [Roman Mstyslavych], re-united all of south-western Rus', including Volhynia, Galicia and Rus' ancient capital of Kiev. Danylo was crowned by the [papal] [archbishop] in [Dorohychyn] 1253 as the first [King] of all Rus'. Under Danylo's reign, the [Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia] was one of the most powerful states in east central Europe.[42]

Foreign domination

In the mid-14th century, upon the death of [Bolesław Jerzy II of Mazovia], king [Casimir III of Poland] initiated campaigns (1340–1366) to take Galicia-Volhynia. Meanwhile, the heartland of Rus', including Kiev, became the territory of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, ruled by [Gediminas] and his successors, after the [Battle on the Irpen' River]. Following the 1386 [Union of Krewo], a [dynastic union] between Poland and Lithuania, much of what became northern Ukraine was ruled by the increasingly Slavicised local Lithuanian nobles as part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. By 1392 the so-called [Galicia–Volhynia Wars] ended. Polish colonisers of depopulated lands in northern and central Ukraine founded or re-founded many towns. In 1430 [Podolia] was incorporated under the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland as [Podolian Voivodeship]. In 1441, in the southern Ukraine, especially Crimea and surrounding steppes, [Genghisid] prince [Haci I Giray] founded the Crimean Khanate.[citation needed]

In 1569 the [Union of Lublin] established the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, and much Ukrainian territory was transferred from Lithuania to the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, becoming Polish territory de jure. Under the demographic, cultural and political pressure of [Polonisation], which began in the late 14th century, many landed gentry of Polish [Ruthenia] (another name for the land of Rus) converted to Catholicism and became indistinguishable from the [Polish nobility].[43] Deprived of native protectors among Rus nobility, the commoners (peasants and townspeople) began turning for protection to the emerging [Zaporozhian Cossacks], who by the 17th century became devoutly [Orthodox]. The Cossacks did not shy from taking up arms against those they perceived as enemies, including the Polish state and its local representatives.[44]

Formed from [Golden Horde] territory conquered after the [Mongol invasion] the [Crimean Khanate] was one of the strongest powers in Eastern Europe until the 18th century; in 1571 it even [captured and devastated Moscow].[45] The borderlands suffered annual [Tatar invasions]. From the beginning of the 16th century until the end of the 17th century, Crimean Tatar [slave raiding] bands[46] exported about two million slaves from Russia and Ukraine.[47] According to [Orest Subtelny], "from 1450 to 1586, eighty-six [Tatar raids] were recorded, and from 1600 to 1647, seventy."[48] In 1688, Tatars captured a record number of 60,000 Ukrainians.[49] The Tatar raids took a heavy toll, discouraging settlement in more southerly regions where the soil was better and the growing season was longer. The last remnant of the Crimean Khanate was finally conquered by the Russian Empire in 1783.[50] The [Taurida Governorate] was formed to govern this territory.[citation needed]

In the mid-17th century, a Cossack military quasi-state, the [Zaporozhian Host], was formed by [Dnieper Cossacks] and by Ruthenian peasants who had fled Polish [serfdom].[51] Poland exercised little real control over this population, but found the Cossacks to be a useful opposing force to the [Turks] and [Tatars],[52] and at times the two were allies in [military campaigns].[53] However the continued harsh [enserfment] of peasantry by Polish nobility and especially the suppression of the Orthodox Church alienated the Cossacks.[52]

The Cossacks sought representation in the Polish [Sejm], recognition of Orthodox traditions, and the gradual expansion of the [Cossack Registry]. These were rejected by the Polish nobility, who dominated the Sejm.[54]

Cossack Hetmanate

In 1648, [Bohdan Khmelnytsky] and [Petro Doroshenko] led the [largest of the Cossack uprisings] against the Commonwealth and the Polish king [John II Casimir].[55] After Khmelnytsky made an entry into Kiev in 1648, where he was hailed liberator of the people from Polish captivity, he founded the [Cossack Hetmanate] which existed until 1764 (some sources claim until 1782).

[Khmelnytsky], deserted by his Tatar allies, suffered a crushing [defeat at Berestechko] in 1651, and turned to the Russian tsar for help. In 1654, Khmelnytsky signed the [Treaty of Pereyaslav], forming a military and political alliance with Russia that acknowledged loyalty to the Russian tsar.

In 1657–1686 came "[The Ruin]", a devastating 30-year war amongst Russia, Poland, Turks and Cossacks for control of Ukraine, which occurred at about the same time as the [Deluge] of Poland. The wars escalated in intensity with hundreds of thousands of deaths. Defeat came in 1686 as the "[Eternal Peace]" between Russia and Poland divided the Ukrainian lands between them.

In 1709, Cossack Hetman [Ivan Mazepa] (1639–1709) defected to [Sweden] against Russia in the [Great Northern War] (1700–1721). Eventually Peter recognized that to consolidate and modernize Russia's political and economic power it was necessary to do away with the [hetmanate] and Ukrainian and Cossack aspirations to autonomy. Mazepa died in exile after fleeing from the [Battle of Poltava] (1709), where the Swedes and their Cossack allies suffered a catastrophic defeat.

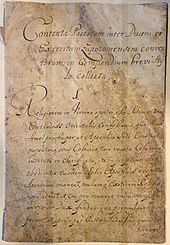

The [Constitution of Pylyp Orlyk] or Pacts and Constitutions of Rights and Freedoms of the Zaporizhian Host was a 1710 constitutional document written by [Hetman] [Pylyp Orlyk], a [Cossack] of Ukraine, then within the [Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth].[56] It established a standard for the [separation of powers] in government between the legislative, executive, and judiciary branches, well before the publication of [Montesquieu]'s [Spirit of the Laws]. The Constitution limited the executive authority of the hetman, and established a democratically elected [Cossack] parliament called the General Council. Pylyp Orlyk's [Constitution] was unique for its historic period, and was one of the first state constitutions in Europe.[citation needed]

The hetmanate was abolished in 1764; the [Zaporizhska Sich] abolished in 1775, as Russia centralised control over its lands. As part of the [partitioning of Poland] in 1772, 1793 and 1795, the Ukrainian lands west of the Dnieper were divided between Russia and Austria. From 1737 to 1834, expansion into the northern Black Sea littoral and the eastern [Danube] valley was a cornerstone of Russian foreign policy.[citation needed]

Lithuanians and Poles controlled vast estates in Ukraine, and were a law unto themselves. Judicial rulings from [Cracow] were routinely flouted, while peasants were heavily taxed and practically tied to the land as [serfs]. Occasionally the landowners battled each other using armies of Ukrainian peasants. The Poles and Lithuanians were Roman Catholics and tried with some success to convert the Orthodox lesser nobility. In 1596, they set up the "Greek-Catholic" or [Uniate Church]; it dominates western Ukraine to this day. Religious differentiation left the Ukrainian Orthodox peasants leaderless, as they were reluctant to follow the Ukrainian nobles.[57]

Cossacks led an uprising, called [Koliivshchyna], starting in the Ukrainian borderlands of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1768. Ethnicity was one root cause of this revolt, which included Ukrainian [violence] that killed tens of thousands of Poles and Jews. Religious warfare also broke out among Ukrainian groups. Increasing conflict between Uniate and Orthodox parishes along the newly reinforced Polish-Russian border on the [Dnieper River] in the time of [Catherine II] set the stage for the uprising. As Uniate religious practices had become more Latinized, Orthodoxy in this region drew even closer into dependence on the Russian Orthodox Church. Confessional tensions also reflected opposing Polish and Russian political allegiances.[58]

After the [Annexation of Crimea by the Russian Empire] in 1783, [New Russia] was settled by Ukrainians and Russians.[59] Despite promises in the Treaty of Pereyaslav, the Ukrainian elite and the Cossacks never received the freedoms and the autonomy they were expecting. However, within the Empire, Ukrainians rose to the highest Russian state and [church] offices.[a] At a later period, [tsarists] established a policy of [Russification], suppressing the use of the Ukrainian language in print and in public.[60]

19th century, World War I and revolution

In the 19th century, Ukraine was a rural area largely ignored by Russia and Austria. With growing urbanization and modernization, and a cultural trend toward [romantic nationalism], a Ukrainian [intelligentsia] committed to national rebirth and social justice emerged. The serf-turned-national-poet [Taras Shevchenko] (1814–1861) and the political theorist [Mykhailo Drahomanov] (1841–1895) led the growing nationalist movement.[citation needed][61]

After the [Russo-Turkish War (1768–1774)], [Catherine the Great] and her immediate successors encouraged German immigration into Ukraine and especially [into Crimea], to thin the previously dominant Turk population and encourage agriculture.[citation needed]

Beginning in the 19th century, there was migration from Ukraine to distant areas of the Russian Empire. According to the 1897 census, there were 223,000 ethnic Ukrainians in [Siberia] and 102,000 in [Central Asia].[62] An additional 1.6 million emigrated to the east in the ten years after the opening of the [Trans-Siberian Railway] in 1906.[63] [Far Eastern] areas with an ethnic Ukrainian population became known as [Green Ukraine].[64]

Nationalist and socialist parties developed in the late 19th century. Austrian [Galicia], under the relatively lenient rule of the [Habsburgs], became the centre of the nationalist movement.[citation needed]

Ukrainians entered [World War I] on the side of both the [Central Powers], under Austria, and the [Triple Entente], under Russia. 3.5 million Ukrainians fought with the [Imperial Russian Army], while 250,000 fought for the [Austro-Hungarian Army].[65] [Austro-Hungarian] authorities established the Ukrainian Legion to fight against the Russian Empire. This became the [Ukrainian Galician Army] that fought against the Bolsheviks and Poles in the post-World War I period (1919–23). Those suspected of Russophile sentiments in Austria were treated harshly.[66]

World War I destroyed both empires. The [Russian Revolution of 1917] led to the founding of the Soviet Union under the [Bolsheviks], and subsequent [civil war in Russia]. A Ukrainian national movement for self-determination re-emerged, with heavy Communist and Socialist influence. Several Ukrainian states briefly emerged: the internationally recognized [Ukrainian People's Republic] (UNR, the predecessor of modern Ukraine, was declared on 23 June 1917 proclaimed at first as a part of the Russian Republic; after the [Bolshevik Revolution], the Ukrainian People's Republic proclaimed its independence on 25 January 1918), the [Hetmanate], the [Directorate] and the pro-Bolshevik [Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic] (or Soviet Ukraine) successively established territories in the former Russian Empire; while the [West Ukrainian People's Republic] and the [Hutsul Republic] emerged briefly in the Ukrainian lands of former Austro-Hungarian territory.[citation needed]

[Act Zluky] (Unification Act) was an agreement signed on January 22, 1919 by the [Ukrainian People's Republic] and the [West Ukrainian People's Republic] on the [St. Sophia Square] in [Kiev].[citation needed]

This led to civil war, and an [anarchist] movement called the [Black Army] or later [The Revolutionary Insurrectionary Army of Ukraine] developed in Southern Ukraine under the command of the anarchist [Nestor Makhno] during the [Russian Civil War].[67] They protected the operation of "[free soviets]" and [libertarian] [communes] in the [Free Territory], an attempt to form a [stateless] [anarchist] society from 1918 to 1921 during the [Ukrainian Revolution], fighting both the tsarist [White Army] under [Denikin] and later the [Red Army] under [Trotsky], before being defeated by the latter in August 1921.

Poland defeated Western Ukraine in the [Polish-Ukrainian War], but failed against the Bolsheviks in [an offensive against Kiev]. According to the [Peace of Riga], western Ukraine was incorporated into Poland, which in turn recognised the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic in March 1919. With establishment of the Soviet power, Ukraine lost half of its territory to Poland, Belarus and Russia, while on the left bank of [Dniester] River was created Moldavian autonomy.[citation needed] Ukraine became a founding member of the [Union of Soviet Socialist Republics] in December 1922.[68]

Western Ukraine, Carpathian Ruthenia and Bukovina

The war in Ukraine continued for another two years; by 1921, however, most of Ukraine had been taken over by the Soviet Union, while Galicia and Volhynia (West Ukraine) were incorporated into independent Poland. [Bukovina] was annexed by Romania and [Carpathian Ruthenia] was admitted to the [Czechoslovak Republic] as an autonomy.[citation needed]

A powerful underground Ukrainian nationalist movement arose in Poland in the 1920s and 1930s because of Polish national policies, which was led by the Ukrainian Military Organization and the [Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN)]. The movement attracted a militant following among students. Hostilities between Polish state authorities and the popular movement led to a substantial number of fatalities, and the autonomy which had been promised was never implemented. A number of Ukrainian parties, the Ukrainian Catholic Church, an active press, and a business sector existed in Poland. Economic conditions improved in the 1920s, but the region suffered from the Great Depression in the 1930s.[citation needed]