The Wall Street Journal - The Cold War’s Tragic Hero

nopaywall

2 сентября 2017 г. Max Boot.

A definitive biography shows a Soviet leader changing his mind. Max Boot reviews ‘Gorbachev’ by William Taubman.

Few figures in the post-1945 world have had as much success in transforming the world as Mikhail Gorbachev —or been as frustrated with the consequences.

He took over as the leader of the Soviet Union in 1985, inheriting the anachronistic title of general secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party along with the creaky infrastructure of a totalitarian state. Private property did not exist. Dissent was outlawed. The Cold War was raging. Eastern Europe was ruled by Soviet satraps. Soviet troops were fighting in Afghanistan.

By the time he left office, at the end of 1991, the Berlin Wall had fallen, the Cold War was over, the Communist Party was no longer in control and the Soviet Union had ceased to exist. Russia, its largest republic, was embarked on an experiment in free-market democracy. By then Mr. Gorbachev had won the Nobel Peace Prize and the adulation of the world. But he was widely reviled at home for leading his country to chaos. Although he fended off a hard-line coup in 1991, he was forced to cede power to his hated rival, Boris Yeltsin, and then watch as Yeltsin’s successor, Vladimir Putin, destroyed the vestiges of Russian democracy.

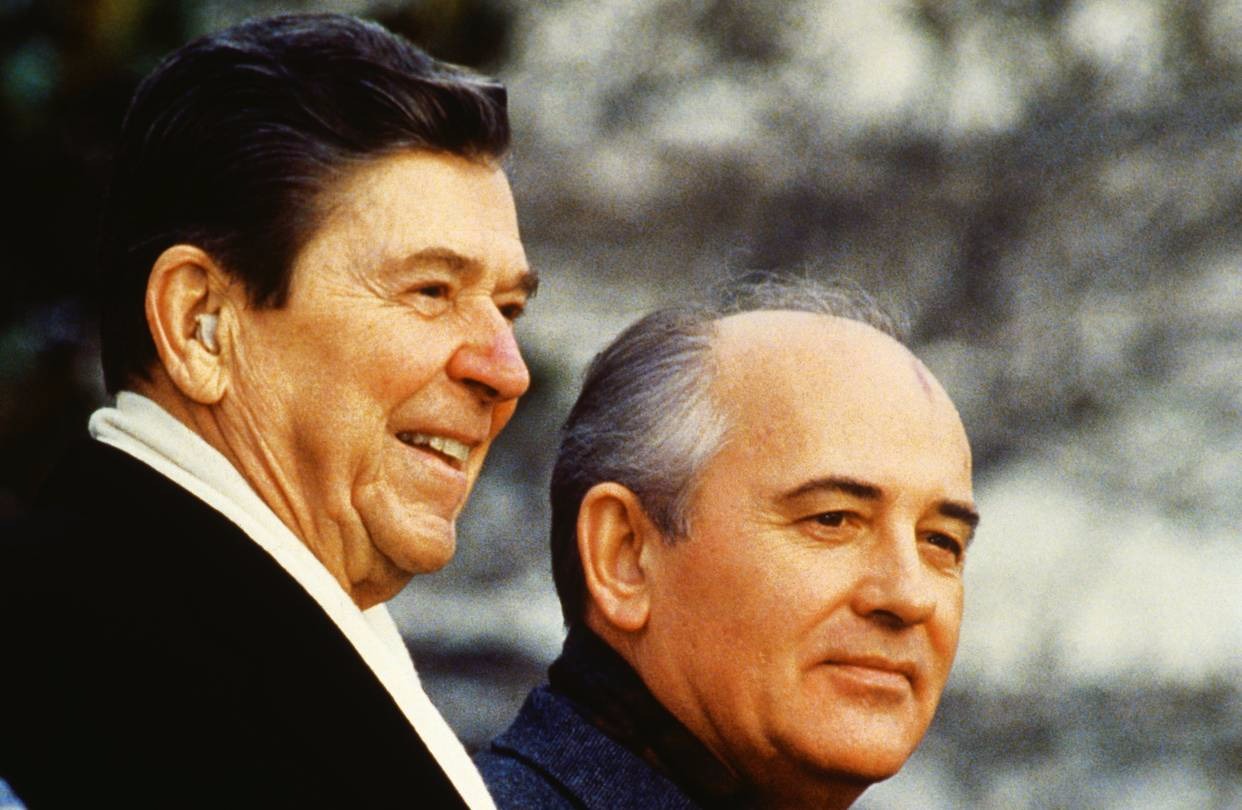

What makes this odyssey all the more stunning is that it had not been forced on Mr. Gorbachev. True, the U.S.S.R. was rundown and impoverished when he took over. It was losing a high-tech arms race, struggling to feed its own people and facing greater pressure from a more assertive America led by Ronald Reagan. But as the examples of North Korea and Cuba demonstrate, even decrepit dictatorships can survive for decades. Continuing repression was a real option but one that Gorbachev never seriously entertained, because by the time he took power he was no longer a Communist true believer but, rather, a European-style social democrat.

How did a closet liberal rise to supreme power in a state created by Lenin and Stalin ? William Taubman, an emeritus professor at Amherst and the author of a Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of Khrushchev, is superbly qualified to answer that question. With “Gorbachev: His Life and Times,” he delivers a meticulously researched, clear-eyed volume that will undoubtedly stand for years as the definitive account of the Soviet Union’s last ruler. His biography is not a thing of literary beauty, but it is reliable and judicious, admiring but never hagiographical.

Mr. Gorbachev was born in 1931 in the village of Privolnoe in Russia’s North Caucasus region. His childhood was hardly placid. As Mr. Taubman notes: “Stalin’s Great Terror of the 1930s swept up both of Gorbachev’s grandfathers: his mother’s father arrested in 1934, his other grandfather in 1937. Then on June 22, 1941, the Nazis invaded the USSR, occupying Gorbachev’s village for four and a half months in 1942. Famine struck again in 1944 and 1946. And following the war, when the Soviet people hoped for a better life at long last, Stalin cracked down again, forcing them to sacrifice once more for the glorious future that Communism promised but never delivered.”

The horrors of Stalinism and World War II left a profound mark on young Mikhail, fostering a lifelong aversion to political repression and military conflict. Yet somehow he emerged from his seemingly horrific upbringing as a happy, optimistic, self-confident fellow. He was lucky that his grandfathers survived the Gulag and that his father survived his military service during the war, even if a false report, in the summer of 1944, announced that he had been killed in action.

Mr. Gorbachev was smart and diligent, and he was blessed with a good education denied to his peasant parents. He became a star pupil at his local schools and then later at the Soviet Union’s premier college, Moscow State University. His path was smoothed by his coming from the perfect Bolshevik background. One of his grandfathers chaired a collective farm, and Mikhail himself became a leader in the Komsomol, the Communist youth organization, and won the Red Labor Banner in 1949 “for helping his combine-driver father break harvesting records.”

At Moscow State, which he entered in 1950, Mr. Gorbachev became close friends with Zdenek Mlynar, a Czech student who would go on to become the chief ideologist of the Prague Spring in 1968. The two men influenced each other as they lost faith in Stalinism and adopted a more humane creed that later became known as “socialism with a human face.”

Mr. Gorbachev was a serious undergraduate with little time for frivolity or dating, but he was smitten by a comely and intelligent fellow student named Raisa Titarenko. His future wife (they married in 1953) thought of herself as an intellectual and went on to do graduate work in sociology. Their romance would be as contented and fulfilling as that of Nancy and Ronald Reagan, even though the insecure Nancy and the know-it-all Raisa could not stand each other.

After graduation, Raisa gave up hopes of an academic career to follow Mikhail back to his home region of Stavropol, where he rose rapidly within the ranks of the Communist Party. Mr. Gorbachev was smarter and harder-working, soberer and more honest than the other apparatchiks, and by 1970 he was party boss of the region. Ten years later, he became a full member of the Politburo, the senior decision-making body within the Soviet Union. Leonid Brezhnev was on his last legs; he died in 1982. His sickly successors, Yuri Andropov and Konstantin Chernenko, also died in short order. Younger and more energetic, Mr. Gorbachev was the natural next-in-line.

And so in 1985 he took absolute power and launched his twin initiatives of perestroika (restructuring) and glasnost (openness). The latter succeeded better than the former. Mr. Gorbachev could not make the Communist system more efficient, and he hesitated to introduce radical free-market reforms that would be opposed by hard-liners. But he had no hesitation about introducing free speech, releasing political prisoners and eventually holding free elections.

At the same time, Mr. Gorbachev pulled out of Afghanistan and cultivated Western leaders such as Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan in a successful attempt to end the Cold War. His most crucial decision occurred in 1989, when he refused to use force to preserve the Communist regimes in Eastern Europe. His forbearance made it possible for Germany to be reunited and its neighbors to join the European Union and NATO.

Like many other revolutionaries, Mr. Gorbachev lost control of the changes he begat. His attempts to reform the Communist system destroyed it, and he ultimately proved better at back-room maneuvering within the Politburo than at winning support from the masses. (Running against Yeltsin, he received 0.5% of the vote in the 1996 presidential election.) But, Mr. Taubman argues, that does not make Mr. Gorbachev a failure: “By introducing free elections and creating parliamentary institutions, he laid the groundwork for democracy. It is more the fault of the raw material he worked with than of his own real shortcomings and mistakes that Russian democracy will take much longer to build than he thought.”

That is a generous judgment—maybe overly generous, given that Russia has returned to autocracy under the former KGB agent Vladimir Putin. Perhaps Russia’s dire straits, with an imploding economy overseen by a corrupt oligarchy, could have been avoided if Mr. Gorbachev had engineered a smoother transition from dictatorship to democracy, from communism to capitalism. But the dissolution of every great empire has been a messy, bloody business. By the standards of the Romans, Mongols, Manchus, Ottomans and Habsburgs, or even the more liberal French and British empires (whose ends caused bloodletting from India to Algeria), Mr. Gorbachev didn’t do so badly. Mr. Taubman is persuasive in calling him “a tragic hero who deserves our understanding and admiration,” even if it is a judgment that few of his countrymen share.

Читайте ещё больше платных статей бесплатно: https://t.me/nopaywall