Quran

SourceThe Quran (, kor-AHN;[i] Arabic: القرآن, romanized: al-Qurʼān, lit. 'the recitation', Arabic pronunciation: [alqurˈʔaːn][ii]) (also romanized Qur'an or Koran,[iii]) is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God (Allah).[11] It is widely regarded as the finest work in classical Arabic literature.[12][13][iv][v] It is organized in 114 chapters (surah (سور; singular: سورة, sūrah)), which consist of verses (āyāt (آيات; singular: آية, āyah)).

Muslims believe that the Quran was orally revealed by God to the final prophet, Muhammad, through the archangel Gabriel (Jibril),[16][17] incrementally over a period of some 23 years, beginning in the month of Ramadan,[18] when Muhammad was 40; and concluding in 632, the year of his death.[11][19][20] Muslims regard the Quran as Muhammad's most important miracle; a proof of his prophethood;[21] and the culmination of a series of divine messages starting with those revealed to Adam, including the Tawrah (Torah), the Zabur ("Psalms") and the Injil ("Gospel"). The word Quran occurs some 70 times in the text itself, and other names and words are also said to refer to the Quran.[22]

The Quran is thought by Muslims to be not simply divinely inspired, but the literal word of God.[23] Muhammad did not write it as he did not know how to write. According to tradition, several of Muhammad's companions served as scribes, recording the revelations.[24] Shortly after the prophet's death, the Quran was compiled by the companions, who had written down or memorized parts of it.[25] Caliph Uthman established a standard version, now known as the Uthmanic codex, which is generally considered the archetype of the Quran known today. There are, however, variant readings, with mostly minor differences in meaning.[24]

The Quran assumes familiarity with major narratives recounted in the Biblical and apocryphal scriptures. It summarizes some, dwells at length on others and, in some cases, presents alternative accounts and interpretations of events.[26][27] The Quran describes itself as a book of guidance for mankind (2:185). It sometimes offers detailed accounts of specific historical events, and it often emphasizes the moral significance of an event over its narrative sequence.[28] Supplementing the Quran with explanations for some cryptic Quranic narratives, and rulings that also provide the basis for sharia (Islamic law) in most denominations of Islam,[29][vi] are hadiths—oral and written traditions believed to describe words and actions of Muhammad.[vii][29] During prayers, the Quran is recited only in Arabic.[30]

Someone who has memorized the entire Quran is called a hafiz ('memorizer'). An ayah (Quranic verse) is sometimes recited with a special kind of elocution reserved for this purpose, called tajwid. During the month of Ramadan, Muslims typically complete the recitation of the whole Quran during tarawih prayers. In order to extrapolate the meaning of a particular Quranic verse, Muslims rely on exegesis, or commentary (tafsir), rather than a direct translation of the text.[31]

The word qurʼān appears about 70 times in the Quran itself, assuming various meanings. It is a verbal noun (maṣdar) of the Arabic verb qaraʼa (قرأ) meaning 'he read' or 'he recited'. The Syriac equivalent is qeryānā (ܩܪܝܢܐ), which refers to 'scripture reading' or 'lesson'.[32] While some Western scholars consider the word to be derived from the Syriac, the majority of Muslim authorities hold the origin of the word is qaraʼa itself.[11] Regardless, it had become an Arabic term by Muhammad's lifetime.[11] An important meaning of the word is the 'act of reciting', as reflected in an early Quranic passage: "It is for Us to collect it and to recite it (qurʼānahu)."[33]

In other verses, the word refers to 'an individual passage recited [by Muhammad]'. Its liturgical context is seen in a number of passages, for example: "So when al-qurʼān is recited, listen to it and keep silent."[34] The word may also assume the meaning of a codified scripture when mentioned with other scriptures such as the Torah and Gospel.[35]

The term also has closely related synonyms that are employed throughout the Quran. Each synonym possesses its own distinct meaning, but its use may converge with that of qurʼān in certain contexts. Such terms include kitāb ('book'), āyah ('sign'), and sūrah ('scripture'); the latter two terms also denote units of revelation. In the large majority of contexts, usually with a definite article (al-), the word is referred to as the waḥy ('revelation'), that which has been "sent down" (tanzīl) at intervals.[36][37] Other related words include: dhikr ('remembrance'), used to refer to the Quran in the sense of a reminder and warning; and ḥikmah ('wisdom'), sometimes referring to the revelation or part of it.[11][viii]

The Quran describes itself as "the discernment" (al-furqān), "the mother book" (umm al-kitāb), "the guide" (huda), "the wisdom" (hikmah), "the remembrance" (dhikr), and "the revelation" (tanzīl; something sent down, signifying the descent of an object from a higher place to lower place).[38] Another term is al-kitāb ('The Book'), though it is also used in the Arabic language for other scriptures, such as the Torah and the Gospels. The term mus'haf ('written work') is often used to refer to particular Quranic manuscripts but is also used in the Quran to identify earlier revealed books.[11]

History

Prophetic era

Islamic tradition relates that Muhammad received his first revelation in the Cave of Hira during one of his isolated retreats to the mountains. Thereafter, he received revelations over a period of 23 years. According to hadith and Muslim history, after Muhammad immigrated to Medina and formed an independent Muslim community, he ordered many of his companions to recite the Quran and to learn and teach the laws, which were revealed daily. It is related that some of the Quraysh who were taken prisoners at the Battle of Badr regained their freedom after they had taught some of the Muslims the simple writing of the time. Thus a group of Muslims gradually became literate. As it was initially spoken, the Quran was recorded on tablets, bones, and the wide, flat ends of date palm fronds. Most suras were in use amongst early Muslims since they are mentioned in numerous sayings by both Sunni and Shia sources, relating Muhammad's use of the Quran as a call to Islam, the making of prayer and the manner of recitation. However, the Quran did not exist in book form at the time of Muhammad's death in 632.[39][40][41] There is agreement among scholars that Muhammad himself did not write down the revelation.[42]

Sahih al-Bukhari narrates Muhammad describing the revelations as, "Sometimes it is (revealed) like the ringing of a bell" and Aisha reported, "I saw the Prophet being inspired Divinely on a very cold day and noticed the sweat dropping from his forehead (as the Inspiration was over)."[ix] Muhammad's first revelation, according to the Quran, was accompanied with a vision. The agent of revelation is mentioned as the "one mighty in power,"[44] the one who "grew clear to view when he was on the uppermost horizon. Then he drew nigh and came down till he was (distant) two bows' length or even nearer."[40][45] The Islamic studies scholar Welch states in the Encyclopaedia of Islam that he believes the graphic descriptions of Muhammad's condition at these moments may be regarded as genuine, because he was severely disturbed after these revelations. According to Welch, these seizures would have been seen by those around him as convincing evidence for the superhuman origin of Muhammad's inspirations. However, Muhammad's critics accused him of being a possessed man, a soothsayer or a magician since his experiences were similar to those claimed by such figures well known in ancient Arabia. Welch additionally states that it remains uncertain whether these experiences occurred before or after Muhammad's initial claim of prophethood.[46]

Muhammad's first revelation, Surah Al-Alaq, later placed 96th in the Qur'anic regulations, in current writing style

Muhammad's first revelation, Surah Al-Alaq, later placed 96th in the Qur'anic regulations, in current writing styleThe Quran describes Muhammad as "ummi,"[47] which is traditionally interpreted as 'illiterate', but the meaning is rather more complex. Medieval commentators such as Al-Tabari maintained that the term induced two meanings: first, the inability to read or write in general; second, the inexperience or ignorance of the previous books or scriptures, (but they gave priority to the first meaning). Muhammad's illiteracy was taken as a sign of the genuineness of his prophethood. For example, according to Fakhr al-Din al-Razi, if Muhammad had mastered writing and reading he possibly would have been suspected of having studied the books of the ancestors. Some scholars such as Watt prefer the second meaning of ummi—they take it to indicate unfamiliarity with earlier sacred texts.[40][48]

The final verse of the Quran was revealed on the 18th of the Islamic month of Dhu al-Hijjah in the year 10 A.H., a date that roughly corresponds to February or March 632. The verse was revealed after the Prophet finished delivering his sermon at Ghadir Khumm.

Compilation and preservation

Following Muhammad's death in 632, a number of his companions who knew the Quran by heart were killed in the Battle of Yamama by Musaylimah. The first caliph, Abu Bakr (d. 634), subsequently decided to collect the book in one volume so that it could be preserved. Zayd ibn Thabit (d. 655) was the person to collect the Quran since "he used to write the Divine Inspiration for Allah's Apostle". Thus, a group of scribes, most importantly Zayd, collected the verses and produced a hand-written manuscript of the complete book. The manuscript according to Zayd remained with Abu Bakr until he died. Zayd's reaction to the task and the difficulties in collecting the Quranic material from parchments, palm-leaf stalks, thin stones (collectively known as suhuf)[49] and from men who knew it by heart is recorded in earlier narratives. After Abu Bakr, in 644, Hafsa bint Umar, Muhammad's widow, was entrusted with the manuscript until the third caliph, Uthman ibn Affan, requested the standard copy from Hafsa bint Umar in about 650.[50]

In about 650, the third Caliph Uthman ibn Affan (d. 656) began noticing slight differences in pronunciation of the Quran as Islam expanded beyond the Arabian Peninsula into Persia, the Levant, and North Africa. In order to preserve the sanctity of the text, he ordered a committee headed by Zayd to use Abu Bakr's copy and prepare a standard copy of the Quran.[39][51] Thus, within 20 years of Muhammad's death, the Quran was committed to written form. That text became the model from which copies were made and promulgated throughout the urban centers of the Muslim world, and other versions are believed to have been destroyed.[39][52][53][54] The present form of the Quran text is accepted by Muslim scholars to be the original version compiled by Abu Bakr.[40][41][x]

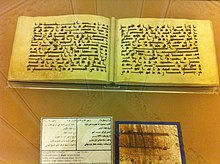

Quran − in Mashhad, Iran − said to be written by Ali

Quran − in Mashhad, Iran − said to be written by AliAccording to Shia, Ali ibn Abi Talib (d. 661) compiled a complete version of the Quran shortly after Muhammad's death. The order of this text differed from that gathered later during Uthman's era in that this version had been collected in chronological order. Despite this, he made no objection against the standardized Quran and accepted the Quran in circulation. Other personal copies of the Quran might have existed including Ibn Mas'ud's and Ubay ibn Ka'b's codex, none of which exist today.[11][39][56]

The Quran most likely existed in scattered written form during Muhammad's lifetime. Several sources indicate that during Muhammad's lifetime a large number of his companions had memorized the revelations. Early commentaries and Islamic historical sources support the above-mentioned understanding of the Quran's early development.[25] University of Chicago professor Fred Donner states that:[57]

[T]here was a very early attempt to establish a uniform consonantal text of the Qurʾān from what was probably a wider and more varied group of related texts in early transmission.… After the creation of this standardized canonical text, earlier authoritative texts were suppressed, and all extant manuscripts—despite their numerous variants—seem to date to a time after this standard consonantal text was established.

Although most variant readings of the text of the Quran have ceased to be transmitted, some still are.[58][59] There has been no critical text produced on which a scholarly reconstruction of the Quranic text could be based.[xi] Historically, controversy over the Quran's content has rarely become an issue, although debates continue on the subject.[61][xii]

The right page of the Stanford '07 binary manuscript. The upper layer is verses 265-271 of the surah Bakara. The double-layer reveals the additions made on the first text of the Quran and the differences with today's Koran.

The right page of the Stanford '07 binary manuscript. The upper layer is verses 265-271 of the surah Bakara. The double-layer reveals the additions made on the first text of the Quran and the differences with today's Koran.In 1972, in a mosque in the city of Sana'a, Yemen, manuscripts were discovered that were later proved to be the most ancient Quranic text known to exist at the time. The Sana'a manuscripts contain palimpsests, a manuscript page from which the text has been washed off to make the parchment reusable again—a practice which was common in ancient times due to scarcity of writing material. However, the faint washed-off underlying text (scriptio inferior) is still barely visible and believed to be "pre-Uthmanic" Quranic content, while the text written on top (scriptio superior) is believed to belong to Uthmanic time.[62] Studies using radiocarbon dating indicate that the parchments are dated to the period before 671 CE with a 99 percent probability.[63][64] The German scholar Gerd R. Puin has been investigating these Quran fragments for years. His research team made 35,000 microfilm photographs of the manuscripts, which he dated to early part of the 8th century. Puin has not published the entirety of his work, but noted unconventional verse orderings, minor textual variations, and rare styles of orthography. He also suggested that some of the parchments were palimpsests which had been reused. Puin believed that this implied an evolving text as opposed to a fixed one.[65]

In 2015, fragments of a very early Quran, dating back to 1370 years earlier, were discovered in the library of the University of Birmingham, England. According to the tests carried out by the Oxford University Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit, "with a probability of more than 95%, the parchment was from between 568 and 645". The manuscript is written in Hijazi script, an early form of written Arabic.[66] This is possibly the earliest extant exemplar of the Quran, but as the tests allow a range of possible dates, it cannot be said with certainty which of the existing versions is the oldest.[66] Saudi scholar Saud al-Sarhan has expressed doubt over the age of the fragments as they contain dots and chapter separators that are believed to have originated later.[67] However Joseph E. B. Lumbard of Brandeis University has written in the Huffington Post in support of the dates proposed by the Birmingham scholars. Lumbard notes that the discovery of a Quranic text that may be confirmed by radiocarbon dating as having been written in the first decades of the Islamic era, while presenting a text substantially in conformity with that traditionally accepted, reinforces a growing academic consensus that many Western skeptical and 'revisionist' theories of Quranic origins are now untenable in the light of empirical findings—whereas, on the other hand, counterpart accounts of Quranic origins within classical Islamic traditions stand up well in the light of ongoing scientific discoveries.[68]

Significance in Islam

Muslims believe the Quran to be God's final revelation to humanity, a work of divine guidance revealed to Muhammad through the angel Gabriel.[19][69]

Revered by pious Muslims as "the holy of holies,"[70] whose sound moves some to "tears and ecstasy",[71] it is the physical symbol of the faith, the text often used as a charm on occasions of birth, death, marriage.[citation needed] Consequently,

It must never rest beneath other books, but always on top of them, one must never drink or smoke when it is being read aloud, and it must be listened to in silence. It is a talisman against disease and disaster.[70][72]

Read Next page