Odessa

Odessa ([Ukrainian]: Оде́са [ɔˈdɛsɐ]; [Russian]: Оде́сса [ɐˈdʲesə]; [Yiddish]: אַדעס) is the third most populous city of [Ukraine] and a major tourism center, seaport and transportation hub located on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. It is also the [administrative center] of the [Odessa Oblast] and a multiethnic cultural center. Odessa is sometimes called the "pearl of the Black Sea",[2] the "South Capital" (under the [Russian Empire] and [Soviet Union]), and "Southern Palmyra".[3]

Before the establishment of Odessa, an [ancient Greek] settlement existed at its location. A relatively more recent [Tatar] settlement was also founded at the location by [Hacı I Giray], the [Khan] of [Crimea] in 1440 that was named after him as "Hacıbey".[4][citation needed] After a period of [Lithuanian Grand Duchy] control, Hacibey and surroundings became part of the domain of the [Ottomans] in 1529 and remained there until the empire's defeat in the [Russo-Turkish War] of 1792.

In 1794, the city of Odessa was founded by a decree of the [Russian empress] [Catherine the Great]. From 1819 to 1858, Odessa was a [free port]. During the Soviet period it was the most important port of trade in the [Soviet Union] and a Soviet [naval base]. On 1 January 2000, the Quarantine Pier at Odessa Commercial Sea Port was declared a free port and [free economic zone] for a period of 25 years.

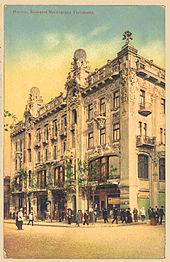

During the 19th century, Odessa was the fourth largest city of Imperial Russia, after [Moscow], [Saint Petersburg] and [Warsaw].[5] Its historical architecture has a style more [Mediterranean] than Russian, having been heavily influenced by French and Italian styles. Some buildings are built in a mixture of different styles, including [Art Nouveau], [Renaissance] and [Classicist].[6]

Odessa is a [warm-water port]. The city of Odessa hosts both the [Port of Odessa] and [Port Yuzhne], a significant oil [terminal] situated in the city's suburbs. Another notable port, [Chornomorsk], is located in the same [oblast], to the south-west of Odessa. Together they represent a major [transport hub] integrating with railways. Odessa's oil and chemical processing facilities are connected to Russian and European networks by strategic [pipelines].

Name

The city was named in compliance with the [Greek Plan] of Catherine the Great. It was named after the ancient Greek city of [Odessos], which was mistakenly believed to have been located here. Although Odessa is located in between the ancient Greek cities of [Tyras] and [Olbia], Odessos is believed to be the predecessor of the present day city of [Varna], Bulgaria.[7]

Catherine's [secretary of state] [Adrian Gribovsky] (ru) claimed in his memoirs that the name was his suggestion. Some expressed doubts about this claim, while others noted the reputation of Gribovsky as an honest and modest man.[8]

History

Early history

Odessa was the site of a large [Greek settlement] no later than the middle of the 6th century BC (a [necropolis] from the 5th–3rd centuries BC has long been known in this area). Some scholars believe it to have been a trade settlement established by Greek city of [Histria]. Whether the Bay of Odessa is the ancient "Port of the Histrians" cannot yet be considered a settled question based on the available evidence.[10] [Archaeological artifacts] confirm extensive links between the Odessa area and the eastern [Mediterranean].

In the Middle Ages successive rulers of the Odessa region included various [nomadic] tribes ([Petchenegs], [Cumans]), the [Golden Horde], the [Crimean Khanate], the [Grand Duchy of Lithuania], and the [Ottoman Empire]. [Yedisan] [Crimean Tatars] traded there in the 14th century.

During the reign of [Khan] [Hacı I Giray] of [Crimea] (1441–1466), the Khanate was endangered by the Golden Horde and the Ottoman Turks and, in search of allies, the khan agreed to cede the area to Lithuania. The site of present-day Odessa was then a fortress known as [Khadjibey] (named for Hacı I Giray, and also spelled Kocibey in [English], Hacıbey or Hocabey in [Turkish], and Hacıbey in [Crimean Tatar]). It was part of the [Dykra] region. However, most of the rest of the area remained largely uninhabited in this period.

Ottoman Yedisan

Khadjibey came under direct control of the Ottoman Empire after 1529 as part of a region known as Yedisan, and was administered in the Ottoman [Silistra (Özi) Province].[citation needed] In the mid-18th century, the Ottomans rebuilt the [fortress] at Khadjibey (also was known Hocabey), which was named Yeni Dünya (literally "New World"). Hocabey was a [sanjak] centre of [Silistre] Province.[citation needed]

In the Russian Empire

The sleepy fishing village that Odessa had been saw a step-change in its fortunes when the wealthy [magnate] and future [Voivode] of [Kiev] (1791), [Antoni Protazy Potocki], set up trade routes through the port for the Polish Black Sea Trading Company and set up the infrastructure in the 1780s.[11]

During the [Russian-Turkish War of 1787–1792], on 25 September 1789, a detachment of the [Russian forces] including Zaporozhian [Cossacks] under [Alexander Suvorov] and [Ivan Gudovich] took Khadjibey and Yeni Dünya for the [Russian Empire]. One part of the troops came under command of a [Spaniard] in Russian service, [Major General] [José de Ribas] (known in Russia as Osip Mikhailovich Deribas), and the main street in Odessa today, [Deribasivska Street], is named after him. Russia formally gained possession of the area as a result of the [Treaty of Jassy] (Iaşi) in 1792 and it became a part of [Novorossiya] ("New Russia").

The city of Odessa, founded by [Catherine the Great], Russian Empress, centers on the site of the Turkish fortress Khadzhibei, which was occupied by Russian Army in 1789. De Ribas and Franz de Volan recommended the area of Khadzhibei fortress as the site for the region's basic port: it had an ice-free harbor, breakwaters could be cheaply constructed and would render the harbor safe and it would have the capacity to accommodate large fleets. The Governor General of Novorossiya, [Platon Zubov] (one of Catherine's favorites) supported this proposal, and in 1794 Catherine approved the founding of the new port-city and invested the first money in constructing the city.

However, adjacent to the new official locality, a [Moldavian] colony already existed, which by the end of the 18th century was an independent settlement known under the name of [Moldavanka]. Some local historians consider that the settlement predates Odessa by about thirty years and assert that the locality was founded by Moldavians who came to build the fortress of Yeni Dunia for the Ottomans and eventually settled in the area in the late 1760s, right next to the settlement of Khadjibey (since 1795 Odessa proper), on what later became the Primorsky Boulevard. Another version posits that the settlement appeared after Odessa itself was founded, as a settlement of Moldavians, Greeks and Albanians fleeing the Ottoman yoke.[12]

In their settlement, also known as Novaya Slobodka, the Moldavians owned relatively small plots on which they built village-style houses and cultivated vineyards and gardens. What became Mykhailovsky Square was the center of this settlement and the site of its first [Orthodox church], the [Church of the Dormition], built in 1821 close to the seashore, as well as of a cemetery. Nearby stood the [military barracks] and the country houses (dacha) of the city's wealthy residents, including that of the [Duc de Richelieu], appointed by Tzar [Alexander I] as Governor of Odessa in 1803.

In the period from 1795 to 1814 the population of Odessa increased 15 times over and reached almost 20 thousand people. The first city plan was designed by the engineer F. Devollan in the late 18th century.[6] Colonists of various ethnicities settled mainly in the area of the former colony, outside of the official boundaries, and as a consequence, in the first third of the 19th century, Moldavanka emerged as the dominant settlement. After planning by the official architects who designed buildings in Odessa's central district, such as the Italians [Francesco Carlo Boffo] and [Giovanni Torricelli], Moldovanka was included in the general city plan, though the original grid-like plan of Moldovankan streets, lanes and squares remained unchanged.[12]

The new city quickly became a major success although initially it received little state funding and privileges.[13] Its early growth owed much to the work of the [Duc de Richelieu], who served as the city's governor between 1803 and 1814. Having fled the [French Revolution], he had served in [Catherine's] army against the Turks. He is credited with designing the city and organizing its amenities and infrastructure, and is considered[by whom?] one of the founding fathers of Odessa, together with another Frenchman, Count [Andrault de Langeron], who succeeded him in office. Richelieu is commemorated by a [bronze statue], unveiled in 1828 to a design by [Ivan Martos]. His contributions to the city are mentioned by [Mark Twain] in his travelogue Innocents Abroad: "I mention this statue and this stairway because they have their story. Richelieu founded Odessa – watched over it with paternal care – labored with a fertile brain and a wise understanding for its best interests – spent his fortune freely to the same end – endowed it with a sound prosperity, and one which will yet make it one of the great cities of the Old World".

In 1819, the city became a free port, a status it retained until 1859. It became home to an extremely diverse population of Albanians, Armenians, Azeris, Bulgarians, Crimean Tatars, Frenchmen, Germans (including Mennonites), Greeks, Italians, Jews, Poles, Romanians, Russians, Turks, Ukrainians, and traders representing many other nationalities (hence numerous "ethnic" names on the city's map, for example Frantsuzky (French) and Italiansky (Italian) Boulevards, Grecheskaya (Greek), Yevreyskaya (Jewish), Arnautskaya (Albanian) Streets). Its [cosmopolitan] nature was documented by the great [Russian poet] [Alexander Pushkin], who lived in [internal exile] in Odessa between 1823 and 1824. In his letters he wrote that Odessa was a city where "the air is filled with all Europe, French is spoken and there are European papers and magazines to read".

Odessa's growth was interrupted by the [Crimean War] of 1853–1856, during which it was bombarded by [British] and [Imperial French] naval forces.[14] It soon recovered and the growth in trade made Odessa Russia's largest grain-exporting port. In 1866, the city was linked by rail with [Kiev] and [Kharkiv] as well as with [Iaşi] in Romania.

The city became the home of a large Jewish community during the 19th century, and by 1897 Jews were estimated to comprise some 37% of the population. The community, however, was repeatedly subjected to [anti-Semitism] and anti-Jewish agitation from almost all Christian segments of the population.[15] [Pogroms] were carried out in [1821, 1859, 1871, 1881 and 1905]. Many Odessan Jews fled abroad after 1882, particularly to the [Ottoman] region that became [Palestine], and the city became an important base of support for [Zionism].

Beginnings of revolution

In 1905, Odessa was the site of a workers' uprising supported by the crew of the [Russian battleship Potemkin] and [Lenin]'s [Iskra]. [Sergei Eisenstein]'s famous motion picture The Battleship Potemkin commemorated the uprising and included a scene where hundreds of Odessan citizens were murdered on the great stone staircase (now popularly known as the "Potemkin Steps"), in one of the most famous scenes in motion picture history. At the top of the steps, which lead down to the port, stands a statue of the [Duc de Richelieu]. The actual massacre took place in streets nearby, not on the steps themselves, but the film caused many to visit Odessa to see the site of the "slaughter". The "Odessa Steps" continue to be a [tourist attraction] in Odessa. The film was made at [Odessa's Cinema Factory], one of the oldest cinema studios in the [former Soviet Union].

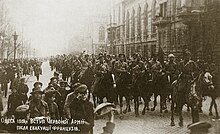

Following the [Bolshevik Revolution] in 1917 during [Ukrainian-Soviet War], Odessa saw two Bolsheviks armed insurgencies, the [second of which] succeeded in establishing their control over the city; for the following months the city became a center of the [Odessa Soviet Republic]. After signing of the [Brest-Litovsk Treaty] all Bolshevik forces were driven out by the combined armed forces of [Central Powers], providing support to the [Ukrainian People's Republic]. With the end of the [World War I] and withdrawal of armies of Central Powers, the Soviet forces fought for control over the country with the army of Ukrainian People's Republic. Few months later the city was occupied by the [French Army] and the [Greek Army] that supported the Russian [White Army] in struggle with the Bolsheviks. The Ukrainian general [Nikifor Grigoriev] who sided with Bolsheviks managed to drive the unwelcome [Triple Entente] forces out of the city, but Odessa was soon retaken by the Russian White Army. Finally by 1920 the Soviet Red Army managed to overpower both Ukrainian and Russian White Army and secure the city.

The people of Odessa badly suffered from a [famine] that occurred as a result of the [Russian Civil War] in 1921–1922 due to the Soviet policies of [prodrazverstka].

- Revolutionary soldiers, Odessa - 1916

World War II

Odessa was attacked by Romanian and German troops in August 1941. The [defense of Odessa] lasted 73 days from 5 August to 16 October 1941. The defense was organized on three lines with emplacements consisting of trenches, AT ditches and pillboxes. The first line was 80 kilometres (50 miles) long and situated some 25 to 30 kilometres (16 to 19 miles) from the city. The second and main line of defense was situated 6 to 8 kilometres (3.7 to 5.0 miles) from the city and was about 30 kilometres (19 miles) long. The third and last line of defense was organised inside the city itself.

[Medal] ["For the Defence of Odessa"] was established on 22 December 1942. Approximately 38,000 people have been awarded (servicemen of the Soviet Army, Navy, Ministry of Internal Affairs, and civil citizens who took part in the defense of Odessa). It was one of the first four Soviet cities to be awarded the title of "[Hero City]" in 1945 ( [Leningrad], [Stalingrad], [Sevastopol], and [Odessa]).

In the battle for Odessa took part the world's best female sniper [Lyudmila Pavlichenko]. Her first 2 kills were made near Belyayevka using a Mosin-Nagant bolt-action rifle with a P.E. 4-power scope. She recorded 187 confirmed kills during defense of Odessa. Pavlichenko's total confirmed kills during World War II was 309 (including 36 snipers).

Before being occupied by Romanian troops in 1941, a part of the city's population, industry, infrastructure and all cultural valuables possible were evacuated to inner regions of the USSR and the retreating Red Army units destroyed as much as they could of Odessa harbour facilities left behind. The city was [land mined] in the same way as Kiev.[citation needed]

During [World War II], from 1941–1944, Odessa was subject to [Romanian] administration, as the city had been made part of [Transnistria].[16] Partisan fighting continued, however, in the [city's catacombs].

Following the [Siege of Odessa], and the [Axis] occupation, approximately 25,000 Odessans were murdered in the outskirts of the city and over 35,000 deported; this came to be known as the [Odessa massacre]. Most of the atrocities were committed during the first six months of the occupation which officially began on 17 October 1941, when 80% of the 210,000 Jews in the region were killed,[17] compared to Jews in Romania proper where the majority survived.[18] After the Nazi forces began to lose ground on the Eastern Front, the Romanian administration changed its policy, refusing to deport the remaining [Jewish population] to extermination camps in German [occupied Poland], and allowing Jews to work as hired labourers. As a result, despite the tragic events of 1941, the survival of the Jewish population in this area was higher than in other areas of occupied eastern Europe.[17]

The city suffered severe damage and sustained many casualties over the course of the war. Many parts of Odessa were damaged during both its siege and recapture on 10 April 1944, when the city was finally liberated by the Red Army. Some of the Odessans had a more favourable view of the Romanian occupation, in contrast with the Soviet official view that the period was exclusively a time of hardship, deprivation, oppression and suffering – claims embodied in public monuments and disseminated through the media to this day.[19] Subsequent Soviet policies imprisoned and executed numerous Odessans (and deported most of the German and Tatar population) on account of collaboration with the occupiers.[20]

Since World War II

During the 1960s and 1970s, the city grew. Nevertheless, the majority of Odessa's Jews emigrated to [Israel], the United States and other Western countries between the 1970s and 1990s. Many ended up in the [Brooklyn] neighborhood of [Brighton Beach], sometimes known as "Little Odessa". Domestic migration of the Odessan middle and [upper classes] to Moscow and [Leningrad], cities that offered even greater opportunities for career advancement, also occurred on a large scale. Despite this, the city grew rapidly by filling the void of those left with new migrants from rural Ukraine and industrial professionals invited from all over the Soviet Union.

As a part of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, the city preserved and somewhat reinforced its unique cosmopolitan mix of Russian/Ukrainian/Jewish culture and a predominantly [Russophone] environment with the [uniquely accented dialect of Russian spoken in the city]. The city's unique identity has been formed largely thanks of its varied demography; all the city's communities have influenced aspects of Odessan life in some way or form.

Odessa is a city of more than 1 million people. The city's industries include shipbuilding, [oil refining], chemicals, metalworking and food processing. Odessa is also a Ukrainian [naval] base and home to a [fishing fleet]. It is known for its large outdoor market – the [Seventh-Kilometer Market], the largest of its kind in Europe.

The city has seen violence in the [2014 pro-Russian conflict in Ukraine] during [2014 Odessa clashes]. The [2 May 2014 Odessa clashes] between pro-Ukrainian and pro-Russian protestors killed 42 people. Four were killed during the protests, and at least 32 trade unionists were killed after a trade union building was set on fire and its exits blocked by Ukrainian nationalists.[21] Polls conducted from September to December 2014 found no support for joining Russia[22]

Odessa was struck by three bomb blasts in December 2014, one of which killed one person (the injuries sustained by the victim indicated that he had dealt with explosives).[23][24] Internal Affairs Ministry advisor [Zorian Shkiryak] said on 25 December that Odessa and Kharkiv had become "cities which are being used to escalate tensions" in Ukraine. Shkiryak said that he suspected that these cities were singled out because of their "geographic position".[23] On 5 January 2015 the city's [Euromaidan] Coordination Center and a cargo train car were (non-lethally) bombed.[25]

Geography

Location

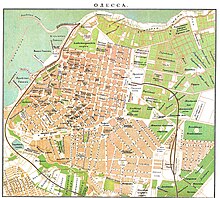

Odessa is situated (46°28′N 30°44′E / 46.467°N 30.733°E / 46.467; 30.733) on terraced hills overlooking a small harbor on the [Black Sea] in the [Gulf of Odessa], approximately 31 km (19 mi) north of the estuary of the [Dniester] river and some 443 km (275 mi) south of the Ukrainian capital [Kiev]. The average elevation at which the city is located is around 50 metres (160 feet), whilst the maximum is 65 metres (213 feet) and minimum (on the coast) amounts to 4.2 metres (13.8 feet) [above sea level]. The city currently covers a territory of 163 km2 (63 sq mi), the population density for which is around 6,139 persons/km². Sources of running water in the city include the Dniester River, from which water is taken and then purified at a processing plant just outside the city. Being located in the south of Ukraine, the topography of the area surrounding the city is typically flat and there are no large mountains or hills for many kilometres around. Flora is of the deciduous variety and Odessa is famous for its beautiful tree-lined avenues which, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, made the city a favourite year-round retreat for the Russian aristocracy.[citation needed]

The city's location on the coast of the [Black Sea] has also helped to create a booming tourist industry in Odessa.[citation needed] The city's famous Arkadia beach has long been a favourite place for relaxation, both for the city's inhabitants and its many visitors. This is a large sandy beach which is located to the south of the city centre. Odessa's many sandy beaches are considered to be quite unique in Ukraine, as the country's southern coast (particularly in the Crimea) tends to be a location in which the formation of stoney and pebble beaches has proliferated.

The coastal cliffs adjacent to the city are home to frequent [landslides], resulting in a typical change of landscape along the Black Sea. Due to the fluctuating slopes of land, city planners are responsible for monitoring the stability of such areas, and for preserving potentially threatened building and other structures of the city [above sea level] near water.[26] Also a potential danger to the infrastructure and architecture of the city is the presence of multiple openings underground. These cavities can cause buildings to collapse, resulting in a loss of money and business. Due to the effects of climate and weather on sedimentary rocks beneath the city, the result is instability under some buildings' foundations.

Climate

Odessa has a hot-summer [humid continental climate] (Dfa, using the 0 °C [32 °F] isotherm) that borderlines the [semi-arid climate] (BSk) as well as a [humid subtropical climate] (Cfa) This has, over the past few centuries, aided the city greatly in creating conditions necessary for the development of summer tourism. During the tsarist era, Odessa's climate was considered to be beneficial for the body, and thus many wealthy but sickly persons were sent to the city in order to relax and recuperate. This resulted in the development of a spa culture and the establishment of a number of high-end hotels in the city. The average annual temperature of sea is 13–14 °C (55–57 °F), whilst seasonal temperatures range from an average of 6 °C (43 °F) in the period from January to March, to 23 °C (73 °F) in August. Typically, for a total of 4 months – from June to September – the average sea temperature in the Gulf of Odessa and city's bay area exceeds 20 °C (68 °F).[27]

The city typically experiences dry, cold winters, which are relatively mild when compared to most of Ukraine as they're marked by temperatures which rarely fall below −10 °C (14 °F). Summers on the other hand do see an increased level of precipitation, and the city often experiences warm weather with temperatures often reaching into the high 20s and low 30s. Snow cover is often light or moderate, and municipal services rarely experience the same problems that can often be found in other, more northern, Ukrainian cities. This is largely because the higher winter temperatures and coastal location of Odessa prevent significant snowfall. Additionally the city does not suffer from the phenomenon of river-freezing.[citation needed]

Demographics

According to the 2001 census, [Ukrainians] make up a majority (62 percent) of Odessa's inhabitants, along with an ethnic [Russian] minority (29 percent).[30]

A 2015 study by the [International Republican Institute] found that 68% of Odessa was ethnic Ukrainian, and 25% ethnic Russian.[31]

Despite the Ukrainian majority, [Russian language] is dominant in the city. In 2015, the languages spoken at home were [Russian] – 78%, [Ukrainian] – 6%, and an equal combination of Ukrainian and Russian – 15%.[31]

Odessa oblast is also home to a number of other nationalities and minority [ethnic groups], including [Albanians], [Armenians], [Azeris], [Crimean Tatars], [Bulgarians], [Georgians], [Greeks], [Jews], [Poles], [Romanians], [Turks], among others.[30] Up until the early 1940s the city also had a large Jewish population. As the result of [mass deportation to extermination camps] during the [Second World War], the city's Jewish population declined considerably. Since the 1970s, the majority of the remaining Jewish population [emigrated to Israel] and other countries, shrinking the Jewish community.

Through most of the 19th century and until the mid 20th century the largest ethnic group in Odessa was [Russians], with the second largest ethnic group being the [Jews].[32]

Historical ethnic and national composition

- 1897[33]

- 1926[34]

- 1939[35]

- 2001[36]

Government and administrative divisions

Whilst Odessa is the [administrative centre] of the [Odessa Oblast] ([province]), the city is also the main constituent of the Odessa Municipality. However, since Odessa is a [city of regional significance], this makes the city subject directly to the administration of the oblast's authorities, thus removing it from the responsibility of the municipality.

The city of Odessa is governed by a mayor and city council which work cooperatively to ensure the smooth-running of the city and procure its municipal bylaws. The city's budget is also controlled by the administration.

The mayoralty[37] plays the role of the executive in the city's municipal administration. Above all comes the mayor, who is elected, by the city's electorate, for five years in a direct election. [2015 Mayoral election of Odessa] [Gennadiy Trukhanov] was reelected in the first round of the election with 52,9% of the vote.[1]

There are five deputy mayors, each of which is responsible for a certain particular part of the city's public policy.

The City Council[38] of the city makes up the administration's [legislative] branch, thus effectively making it a city 'parliament' or [rada]. The municipal council is made up of 120 elected members,[39] who are each elected to represent a certain district of the city for a four-year term. The current council is the fifth in the city's modern history, and was elected in January 2011. In the regular meetings of the municipal council, problems facing the city are discussed, and annually the city's budget is drawn up. The council has seventeen standing commissions[40] which play an important role in controlling the finances and trading practices of the city and its merchants.

The territory of Odessa is divided into four administrative [raions] (districts):

- Kyivsky Raion (Russian: Киевский район, Ukrainian: Київський район)

- Malynovsky Raion (Russian: Малиновский район, Ukrainian: Малиновський район)

- Prymorsky Raion (Russian: Приморский район, Ukrainian: Приморський район)

- Suvorovsky Raion (Russian, Суворовский Район, Ukrainian: Суворовський район)

In addition, every [raion] has its own administration, subordinate to the Odessa [City council], and with limited responsibilities.