Maestro!

Passing the Baton

coda |ˈkōdə| noun music: the concluding passage of a piece or movement, typically forming an addition to the basic structure of a composition.

I quit shooting years ago. It’s time to throw my lens cap back in the ring.

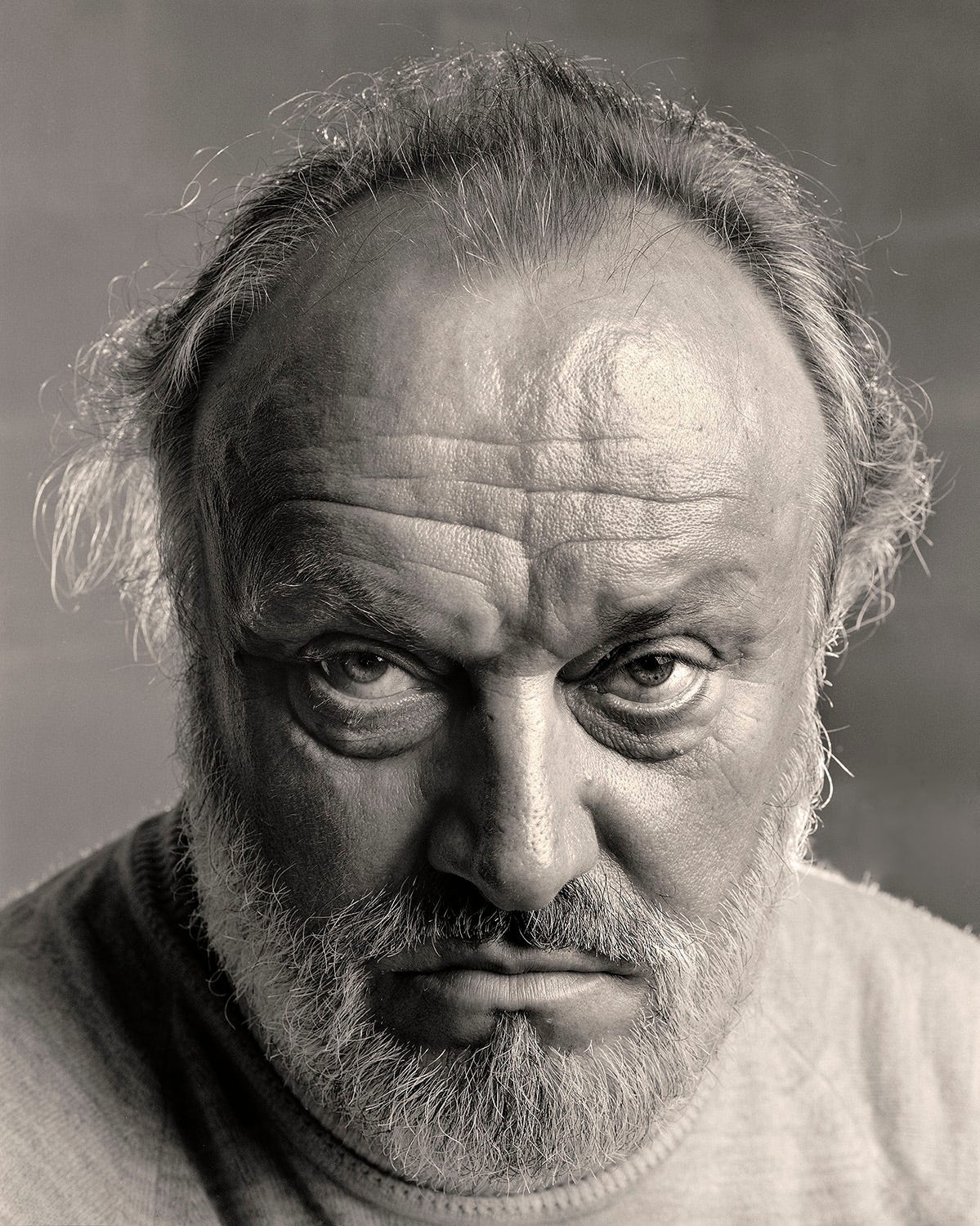

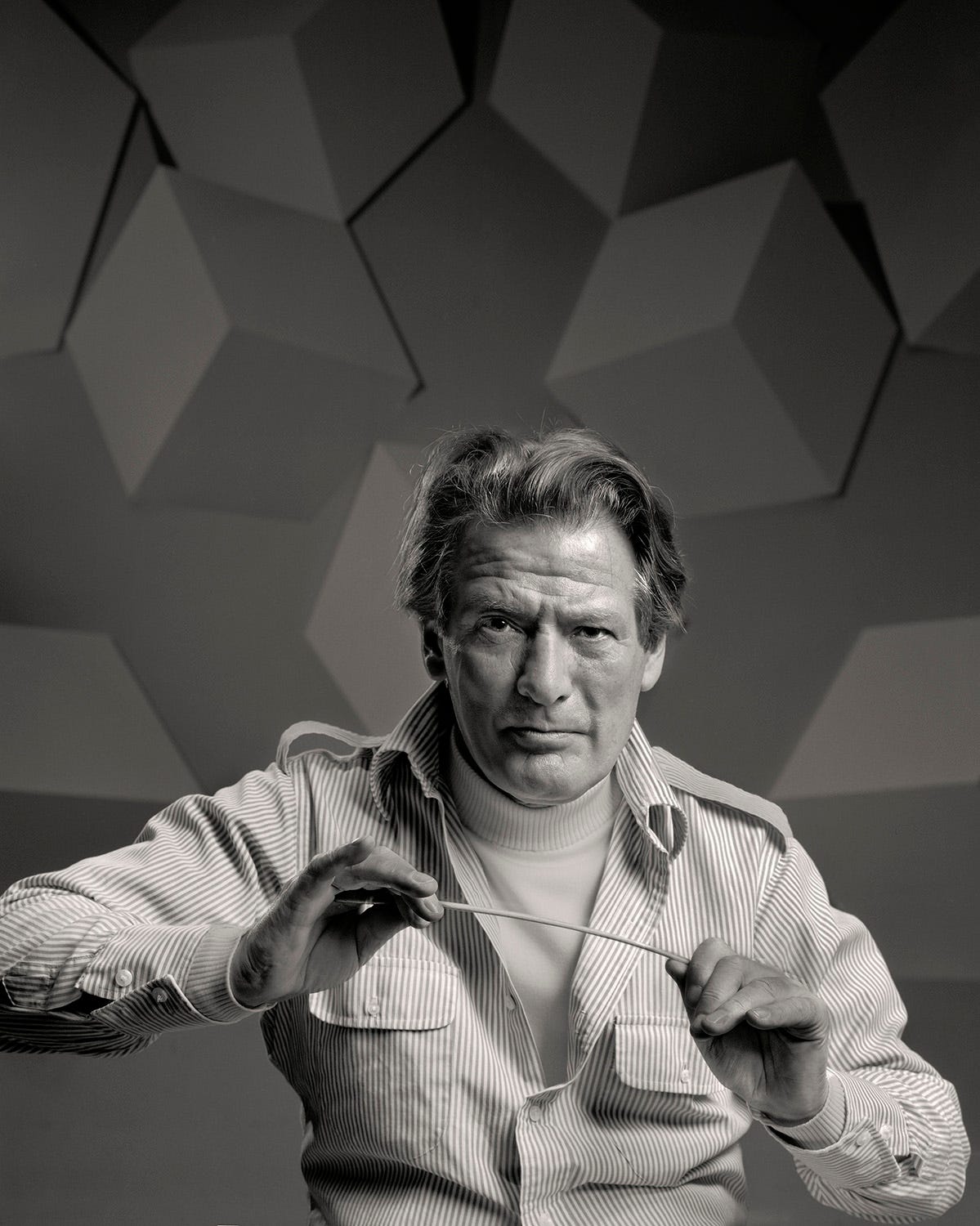

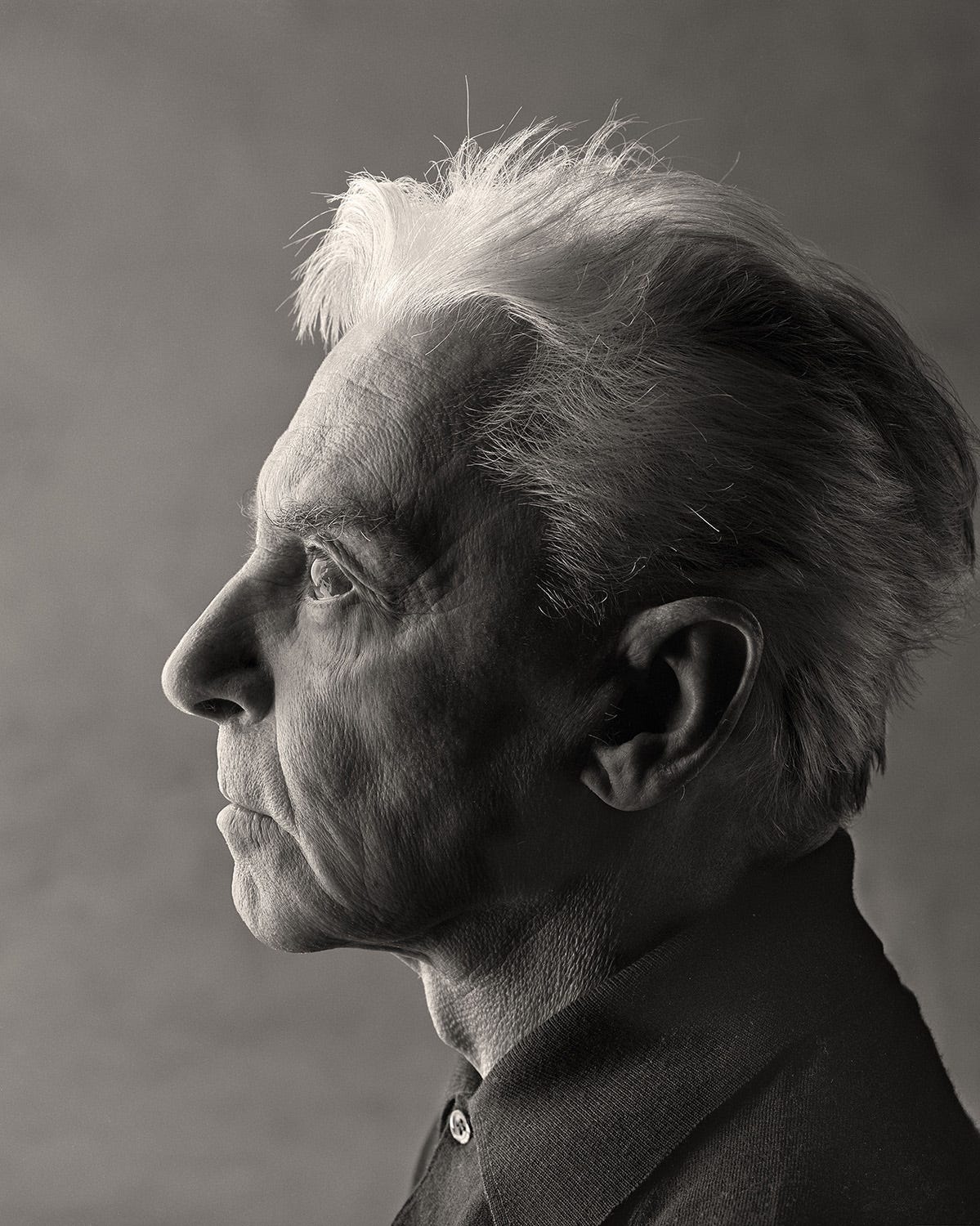

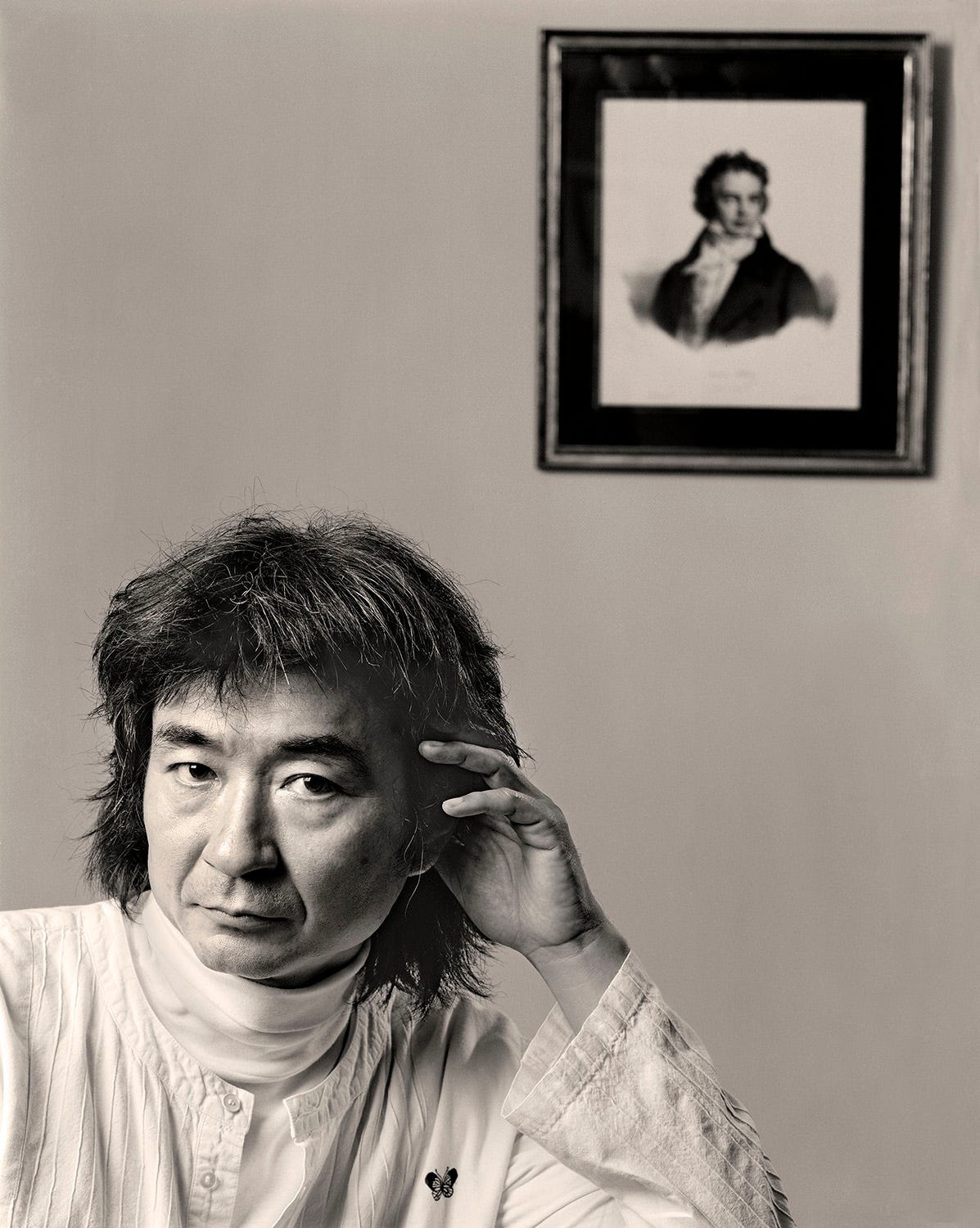

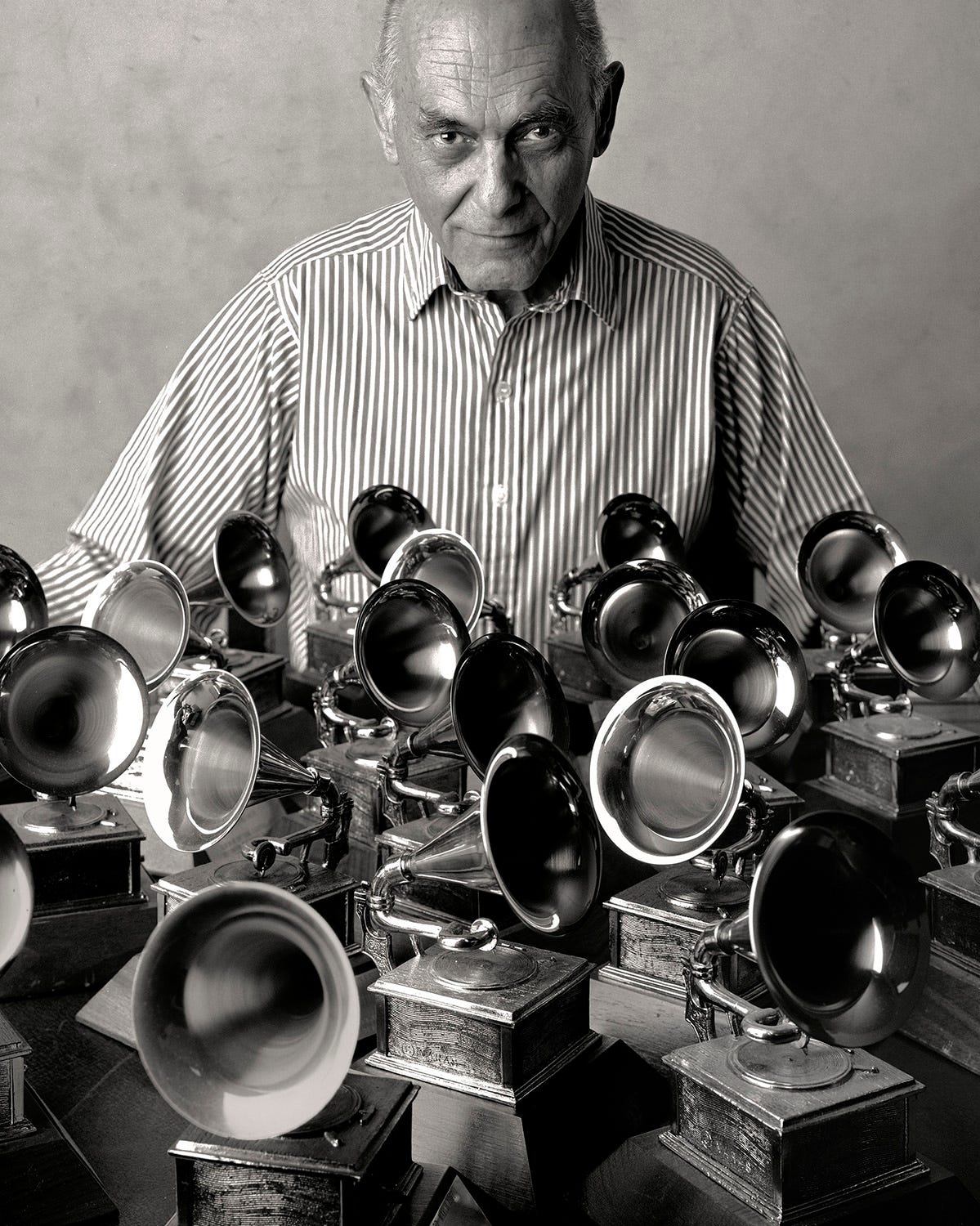

Traveling throughout the United States and Europe from 1979 through 1984, in between paid photo assignments and with partial support from Eastman Kodak Company and Continental Airlines, I made fifty-five portraits of symphony orchestra conductors; exemplars of the twentieth century — almost every living maestro from Abbado to Zinman. I shot sheets of 4x5-inch black-and-white film. I made dramatically large prints. I called my collection Maestro!. The entire opus hung in San Francisco’s Davies Symphony Hall for several months, followed by a nearly decade-long exhibit at the San Francisco Museum of Performance & Design.

No one had attempted anything like Maestro! before. No one has carried on since. It demands a coda: Passing the Baton.

Inspiration

Ansel Adams, arguably the most recognized name in photography, was also an accomplished pianist. He was far better known for his work with a camera than a keyboard, but his equal affinity with both led him famously to compare the negative of a photograph to the score of a symphony. That struck a chord with me.

In the context of his renown for making exquisitely composed black-and-white prints with a sublime tonal range, Adams implied two connected thoughts:

I am a classically trained clarinetist who, like Adams, planned a career in music then pivoted to photography. When I first read his comment decades ago, comparing the negative to the score, it was immediately clear to me that conductors (not composers) account for the musical side of this metamorphosis. I knew conductors. I played under them. Their personalities are as diverse as the music they perform and their approaches to it. Yet almost all of the photographs of conductors I had seen looked pretty much the same, a cliché: standing at a podium, baton flailing.

Adams’s simile inspired me to photograph conductors — differently.

Rationale

Music is hailed as a universal language. Photography, too, speaks to all comers with no translation required. Music and photography both speak to audiences with — just maybe — more immediacy than other art forms; an emotional and trenchant impact that upstages any after-the-fact critical analysis. They smack you in the gut before you can think about what you just heard or saw. As novelist and essayist Stanley Elkin wrote, “In prose, music is very hard to do, unconvincing as lyrics, a cappella on a page.” It’s easy for me to say that music and photography are equally more evocative than words. Nevertheless, I’ve got it on good authority that one picture is worth a thousand of them. I’m sure the same goes for a symphony.

What good is a photograph if no one can see it? What good is a symphony if no one can hear it? A symphony lies dormant, a cipher of dots and lines and squiggles scrawled on paper — “chicken scratches” — until someone transmogrifies this silent score into a philharmonic experience. A photograph lies dormant, too, photons fixed on film or a computer chip, virtually invisible until — hocus focus — someone makes a print.

Like the camera and lens, the orchestra is a complex tool comprised of many parts for creating art. It is the instrument conductors play. They revisit concert halls and recording studios with one or another version of this instrument throughout their careers, often repeating familiar compositions, sometimes for the same audience. Photographers, too, albeit solitarily, return to their darkrooms or Photoshop® to reinterpret earlier prints. Rarely will two prints made at different times from the same negative — or from the same digitally-captured image — look exactly alike; nor will subsequent renditions of a composer’s score by any given conductor sound exactly alike, given so many different orchestras to lead, the vagaries of concert hall acoustics, the vibe of any given audience, a myriad of recording techniques, and the caprice of artistic license.

My point is, Adams’s clever insight about the similarity of a score and a (film) negative helped me collect my own inchoate thoughts vis-à-vis music and photography, and understand why both disciplines appealed to me early in my life as outlets for self-expression.

Photography means to write with light, from Greek. Symphony and orchestra, also Greek words, refer to the structure and mechanics of performing music on a grand scale. The word music itself derives from Greek. Apparently, it’s all Greek to me. So what more harmonious encomium to conductors can a photographer concoct, fluent in the lexicon of light, than to illustrate artists whose virtuosity speaks to the human spirit in the language of sound?

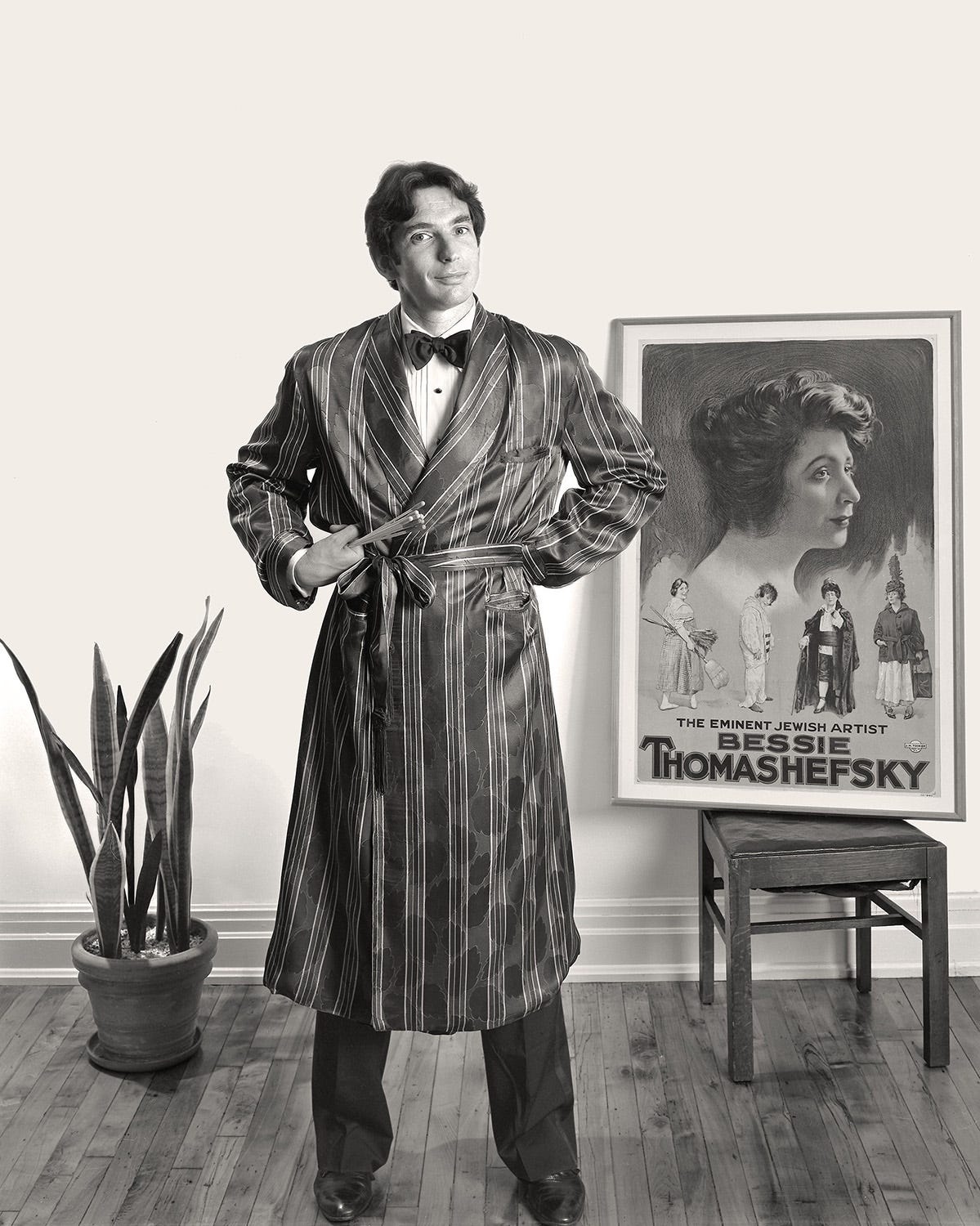

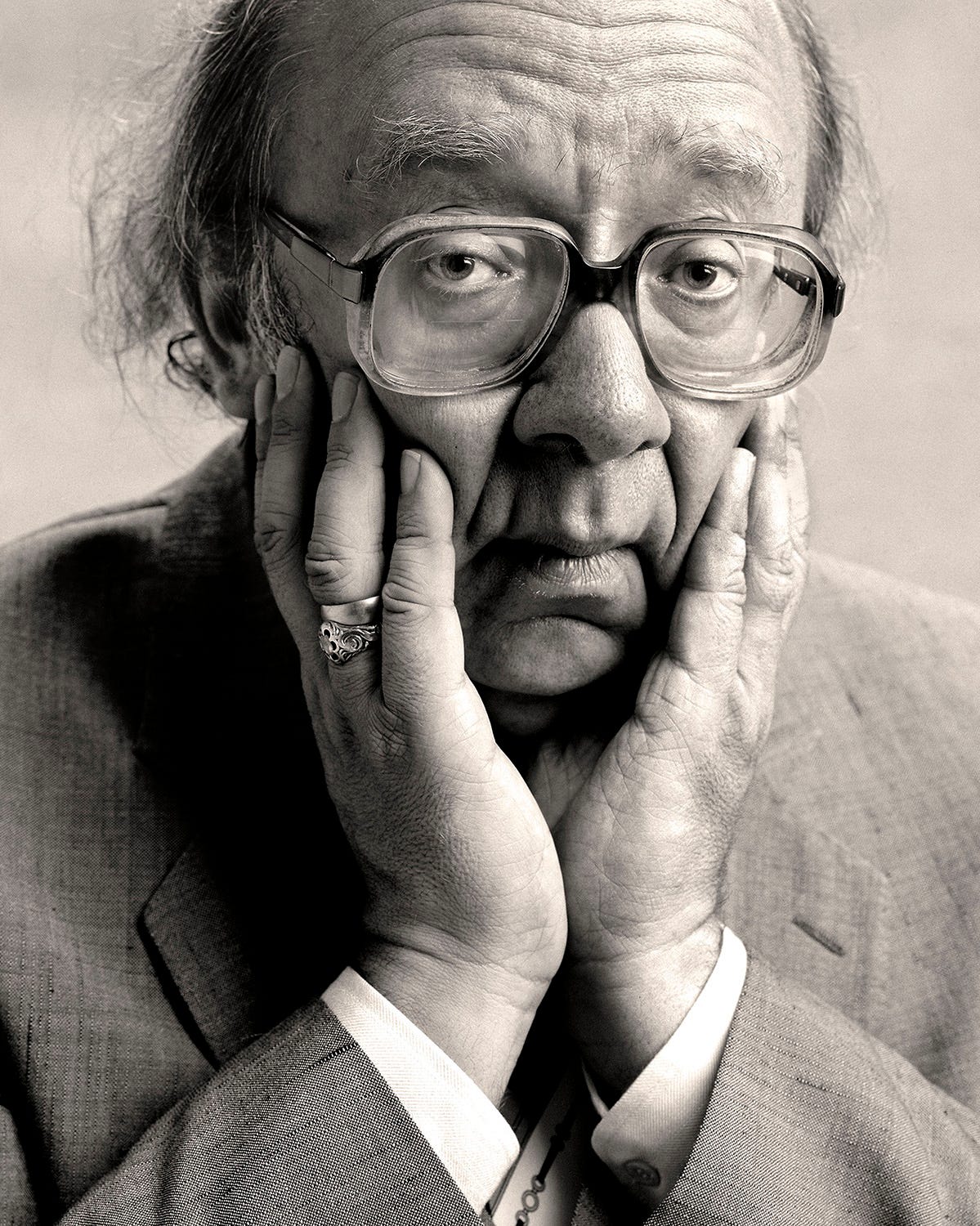

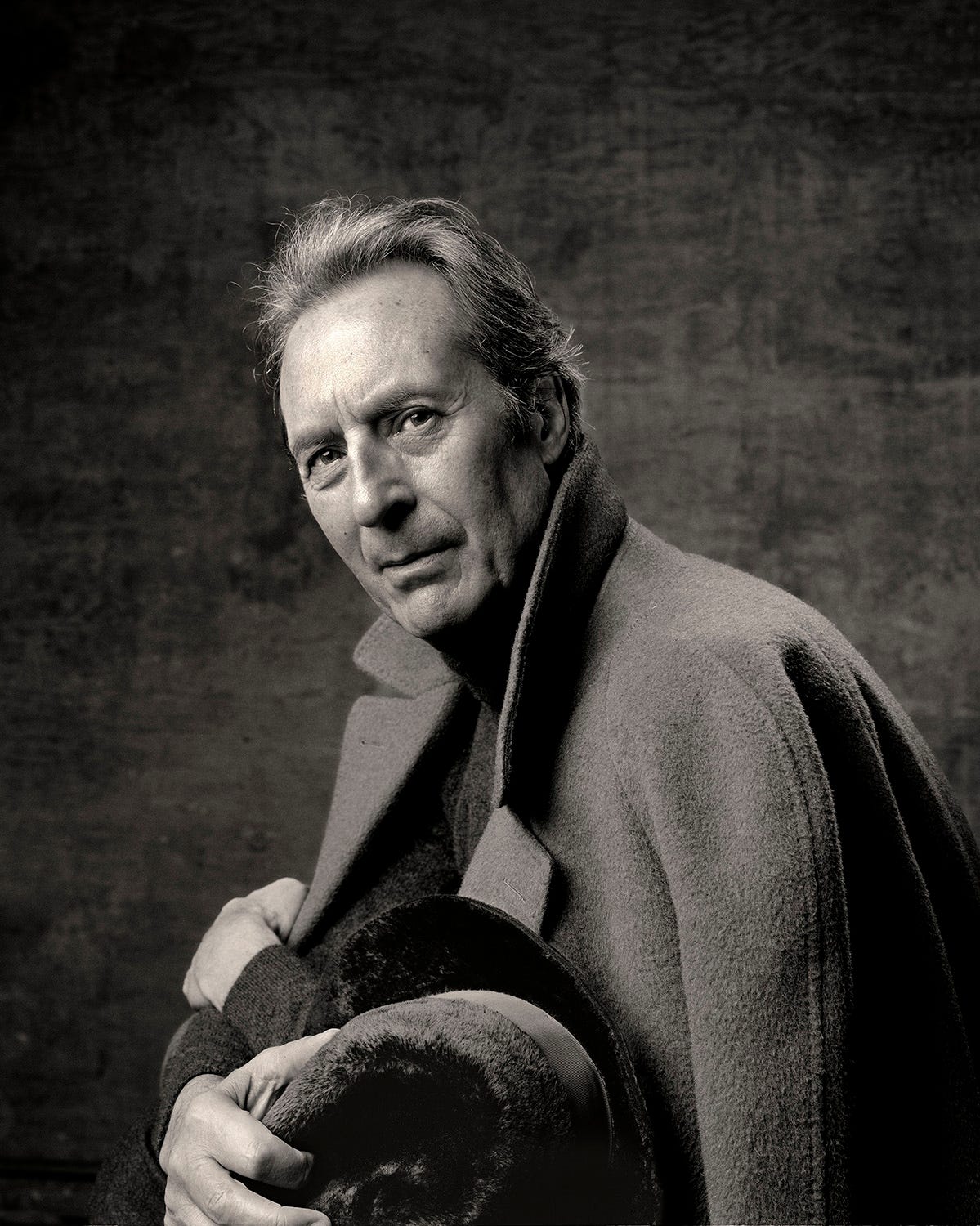

Description

Conductors are a mixed bag of characters, not much alike if you take away their batons, their orchestras. Yet photographers seem to have been determined to make them all look alike by almost always illustrating what they do, but rarely who they are; professional not personal. For instance, in my opinion, the sartorial conformity of white tie and tails has adorned too many record album covers and tediously posed pictures published in concert playbills, let alone every TV and movie characterization or news media depiction of a conductor online or in print. So, first of all, I decided to torpedo the tuxedo. And further, by portraying so many conductors with a deliberate theme of portraiture in mind, I could continue to eschew adding to a glut of hackneyed caricatures of the Maestro: a baton swung through space in a dark concert hall; action frozen in time, replete with imploring gesture, rapturous paroxysm and histrionic contortion. You’ve seen that picture a million times, a visual trope that goes hand in hand with what New Yorker critic David Denby tagged, the “middlebrow music-appreciation racket.” It is an unmistakable meme for classical music, much like the portentous and percussive opening bars of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony sound familiar to anyone who wouldn’t know a portamento from a portmanteau, a cadenza from a credenza, or a pizzicato from a pizza. Stereophonic phonographs, yes; stereotyped photographs, no!

Typically, when requests to shoot the maestro go through official orchestra- or artist-management channels, photographers are obliged to use a telephoto lens from either backstage or offstage during a concert or rehearsal. We are supposed to make ourselves invisible and inaudible. Instead, I ask my subjects to engage with me, to collaborate for several hours and sometimes several days. I demand an opportunity to scout locations ahead of time, to choose backgrounds and props. I insist that each photo session be private, uninterrupted, and preceded by enough time alone with each conductor for us to get acquainted; not only to establish rapport but so I can observe any personal quirks worth capturing before planting a camera on a tripod between us.

That kind of cooperation is hard to get. For one thing, conductors fly around the globe like subatomic particles jumping from the nucleus of one orchestra to another at such a frenetic pace that I might have called this project Musical Chairs; it’s hard to stop the music and sit each conductor down for a photo shoot. I know I’ll have to travel to where any one of them is expected to be, as often as I’ll have to wait for one of them or another to arrive where I already am. And I’ll have to penetrate a bulwark of handlers, personal agents, who see little distinction between routine publicity headshots and conscientious portraiture. They rarely hide their disdain for the impudence of a photographer who would impose on their client’s time. I’ve learned that success may follow the path of least resistance, but failure follows the path of least persistence.

Passing the Baton will extend a photographic bridge from the twentieth century to a continuum of twenty-first-century conductors, commemorating those to whom the baton has indeed been passed. It will be the only all-inclusive portrayal of this pantheon of artists, bringing the public literally face to face with the most rarified musicians in the world — who otherwise have their backs to the audience while performing.

I hope each portrait will be appreciated as a photographic grace note to the phonographic recordings that are each conductor’s legacy.

LINK: Additional “Maestro!” Portraits

Conductors Already Photographed for “Maestro!”

Leonard Bernstein, Claudio Abbado, Vladimir Ashkenazy, Herbert Blömstedt, Pierre Boulez, Myung-whun Chung, George Cleve, Sergiu Comissiona, James Conlon, Sir Colin Davis, Christoph von Dohnanyi, Antal Dorati, Charles Dutoit, Sixten Ehrling, Christoph Eschenbach, Lukas Foss, JoAnn Falletta, Carlo Maria Giulini, Bernard Haitink, Christopher Hogwood, Herbert von Karajan, Christopher Keene, Erich Leinsdorf, James Levine, Jesus Lopez-Cobos, Loren Maazel, Sir Charles Mackerras, Sir Neville Marriner, Kurt Masur, Zubin Mehta, Jorge Mester, Michael Morgan, Eugene Ormandy, Seiji Ozawa, André Previn, Eve Queller, Simon Rattle, Mstislav Rostropovich, Gennadi Rozhdestvensky, Julius Rudel, Esse-Pekka Salonen, Kurt Sanderling, Gerard Schwarz, Calvin Simmons, Leonard Slatkin, Nicolas Slonimsky, Sir Georg Solti, Michael Tilson Thomas, Edo de Waart, David Zinman, Pinchus Zukerman

Conductors to Photograph for “Passing the Baton”:

Alan Gilbert, Alice Farnham, Alondra de la Parra, Andrey Boreyko, Andris Nelsons, Anne Manson, Barbara Hannigan, Christian Thielemann, Daniel

Barenboim, Daniele Gatti, Daniel Harding, David Robertson, Donald Runnicles, Elim Chan, Emmanuelle Haïm, Fabio Luisi, Franz Welser-Möst, Gianandrea Noseda, Grant Llewellyn, Gustavo Dudamel, Hugh Wolff, Ingo Netzmacher, Iván Fischer, Jane Glover, Jaap van Zweden, Jaime Laredo, Jeffrey Kahane, Joana Carneiro, John Mauceri, Jonathan Nott, Karina Canellakis, Keri-Lynn Wilson, Keith Lockhart, Kent Nagano, Krzysztof Urbański, Lothar Zagrosek, Ludovic Morlot, Laura Jackson, Manfred Honeck, Marc Albrecht, Marek Janowski, Marin Alsop, Mariss Jansons, Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla, Neeme Järvi , Nello Santi, Osmo Vänskä, Paavo Järvi, Pablo Heras-Casado, Riccardo Chailly, Riccardo Muti, Roger Nierenberg, Semyon Bychkov, Sian Edwards, Sir Andrew Davis, Susanna Mälkki, Thierry Fischer, Valery Gergiev, Ward Stare , Yannick Nézet-Séguin, Yu Long, Yuri Temirkanov, Xian Zhang,