Jazz

FromThere was a resurgence of interest in jazz and other forms of African-American cultural expression during the Black Arts Movement and Black nationalist period of the 1960s and 1970s. African themes became popular, and many new jazz compositions were given African-related titles: "Black Nile" (Wayne Shorter), "Blue Nile" (Alice Coltrane), "Obirin African" (Art Blakey), "Zambia" (Lee Morgan), "Appointment in Ghana" (Jackie McLean), "Marabi" (Cannonball Adderley), "Yoruba" (Hubert Laws), and many more. Pianist Randy Weston's music incorporated African elements, such as in the large-scale suite "Uhuru Africa" (with the participation of poet Langston Hughes) and "Highlife: Music From the New African Nations." Both Weston and saxophonist Stanley Turrentine covered the Nigerian Bobby Benson's piece "Niger Mambo", which features Afro-Caribbean and jazz elements within a West African Highlife style. Some musicians, including Pharoah Sanders, Hubert Laws, and Wayne Shorter, began using African instruments such as kalimbas, bells, beaded gourds and other instruments which were not traditional to jazz.

Rhythm

During this period, there was an increased use of the typical African 12/8 cross-rhythmic structure in jazz. Herbie Hancock's "Succotash" on Inventions and Dimensions (1963) is an open-ended modal 12

8 improvised jam, in which Hancock's pattern of attack-points, rather than the pattern of pitches, is the primary focus of his improvisations, accompanied by Paul Chambers on bass, percussionist Osvaldo Martinez playing a traditional Afro-Cuban chekeré part and Willie Bobo playing an Abakuá bell pattern on a snare drum with brushes.

The first jazz standard composed by a non-Latino to use an overt African 12

8 cross-rhythm was Wayne Shorter's "Footprints" (1967).[155] On the version recorded on Miles Smiles by Miles Davis, the bass switches to a 4

4 tresillo figure at 2:20. "Footprints" is not, however, a Latin jazz tune: African rhythmic structures are accessed directly by Ron Carter (bass) and Tony Williams (drums) via the rhythmic sensibilities of swing. Throughout the piece, the four beats, whether sounded or not, are maintained as the temporal referent. The following example shows the 12

8 and 4

4 forms of the bass line. The slashed noteheads indicate the main beats (not bass notes), where one ordinarily taps their foot to "keep time."

> \new Staff << \new voice { \clef bass \time 12/8 \key c \minor \set Staff.timeSignatureFraction = 4/4 \scaleDurations 3/2 { \set Score.tempoHideNote = ##t \tempo 8 = 100 \stemDown \override NoteHead.style = #'cross \repeat volta 2 { es,4 es es es } } } \new voice \relative c' { \time 12/8 \set Staff.timeSignatureFraction = 4/4 \scaleDurations 3/2 { \set Score.tempoHideNote = ##t \tempo 4 = 100 \stemUp \repeat volta 2 { c,8. g'16~ g8 c es4~ es8. g,16 } \bar ":|." } } >> >> }

> \new Staff << \new voice { \clef bass \time 12/8 \key c \minor \set Staff.timeSignatureFraction = 4/4 \scaleDurations 3/2 { \set Score.tempoHideNote = ##t \tempo 8 = 100 \stemDown \override NoteHead.style = #'cross \repeat volta 2 { es,4 es es es } } } \new voice \relative c' { \time 12/8 \set Staff.timeSignatureFraction = 4/4 \scaleDurations 3/2 { \set Score.tempoHideNote = ##t \tempo 4 = 100 \stemUp \repeat volta 2 { c,8. g'16~ g8 c es4~ es8. g,16 } \bar ":|." } } >> >> }">

Pentatonic scales

The use of pentatonic scales was another trend associated with Africa. The use of pentatonic scales in Africa probably goes back thousands of years.[156]

McCoy Tyner perfected the use of the pentatonic scale in his solos,[157] and also used parallel fifths and fourths, which are common harmonies in West Africa.[158]

The minor pentatonic scale is often used in blues improvisation, and like a blues scale, a minor pentatonic scale can be played over all of the chords in a blues. The following pentatonic lick was played over blues changes by Joe Henderson on Horace Silver's "African Queen" (1965).[159]

Jazz pianist, theorist, and educator Mark Levine refers to the scale generated by beginning on the fifth step of a pentatonic scale as the V pentatonic scale.[160]

C pentatonic scale beginning on the I (C pentatonic), IV (F pentatonic), and V (G pentatonic) steps of the scale.[clarification needed]

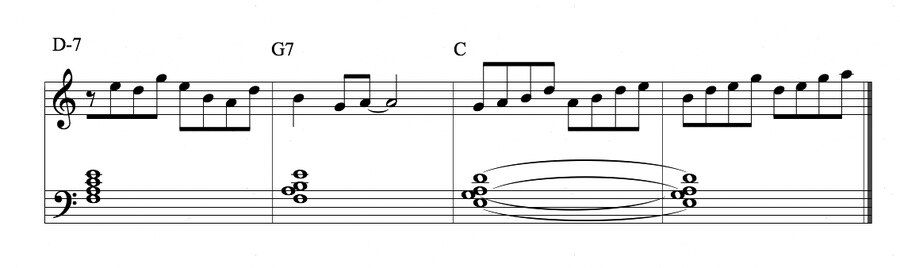

C pentatonic scale beginning on the I (C pentatonic), IV (F pentatonic), and V (G pentatonic) steps of the scale.[clarification needed]Levine points out that the V pentatonic scale works for all three chords of the standard II-V-I jazz progression.[161] This is a very common progression, used in pieces such as Miles Davis' "Tune Up." The following example shows the V pentatonic scale over a II-V-I progression.[162]

V pentatonic scale over II-V-I chord progression.

V pentatonic scale over II-V-I chord progression.Accordingly, John Coltrane's "Giant Steps" (1960), with its 26 chords per 16 bars, can be played using only three pentatonic scales. Coltrane studied Nicolas Slonimsky's Thesaurus of Scales and Melodic Patterns, which contains material that is virtually identical to portions of "Giant Steps".[163] The harmonic complexity of "Giant Steps" is on the level of the most advanced 20th-century art music. Superimposing the pentatonic scale over "Giant Steps" is not merely a matter of harmonic simplification, but also a sort of "Africanizing" of the piece, which provides an alternate approach for soloing. Mark Levine observes that when mixed in with more conventional "playing the changes", pentatonic scales provide "structure and a feeling of increased space."[164]

Jazz fusion

Fusion trumpeter Miles Davis in 1989

Fusion trumpeter Miles Davis in 1989In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the hybrid form of jazz-rock fusion was developed by combining jazz improvisation with rock rhythms, electric instruments and the highly amplified stage sound of rock musicians such as Jimi Hendrix and Frank Zappa. Jazz fusion often uses mixed meters, odd time signatures, syncopation, complex chords, and harmonies.

According to AllMusic:

... until around 1967, the worlds of jazz and rock were nearly completely separate. [However, ...] as rock became more creative and its musicianship improved, and as some in the jazz world became bored with hard bop and did not want to play strictly avant-garde music, the two different idioms began to trade ideas and occasionally combine forces.[165]

Miles Davis' new directions

In 1969, Davis fully embraced the electric instrument approach to jazz with In a Silent Way, which can be considered his first fusion album. Composed of two side-long suites edited heavily by producer Teo Macero, this quiet, static album would be equally influential to the development of ambient music.

As Davis recalls:

The music I was really listening to in 1968 was James Brown, the great guitar player Jimi Hendrix, and a new group who had just come out with a hit record, "Dance to the Music", Sly and the Family Stone ... I wanted to make it more like rock. When we recorded In a Silent Way I just threw out all the chord sheets and told everyone to play off of that.[166]

Two contributors to In a Silent Way also joined organist Larry Young to create one of the early acclaimed fusion albums: Emergency! by The Tony Williams Lifetime.

Psychedelic-jazz

Weather Report

Weather Report's self-titled electronic and psychedelic Weather Report debut album caused a sensation in the jazz world on its arrival in 1971, thanks to the pedigree of the group's members (including percussionist Airto Moreira), and their unorthodox approach to music. The album featured a softer sound than would be the case in later years (predominantly using acoustic bass with Shorter exclusively playing soprano saxophone, and with no synthesizers involved), but is still considered a classic of early fusion. It built on the avant-garde experiments which Joe Zawinul and Shorter had pioneered with Miles Davis on Bitches Brew, including an avoidance of head-and-chorus composition in favour of continuous rhythm and movement – but took the music further. To emphasise the group's rejection of standard methodology, the album opened with the inscrutable avant-garde atmospheric piece "Milky Way", which featured by Shorter's extremely muted saxophone inducing vibrations in Zawinul's piano strings while the latter pedalled the instrument. Down Beat described the album as "music beyond category", and awarded it Album of the Year in the magazine's polls that year.

Weather Report's subsequent releases were creative funk-jazz works.[167]

Jazz-rock

Although some jazz purists protested against the blend of jazz and rock, many jazz innovators crossed over from the contemporary hard bop scene into fusion. As well as the electric instruments of rock (such as electric guitar, electric bass, electric piano and synthesizer keyboards), fusion also used the powerful amplification, "fuzz" pedals, wah-wah pedals and other effects that were used by 1970s-era rock bands. Notable performers of jazz fusion included Miles Davis, Eddie Harris, keyboardists Joe Zawinul, Chick Corea, and Herbie Hancock, vibraphonist Gary Burton, drummer Tony Williams (drummer), violinist Jean-Luc Ponty, guitarists Larry Coryell, Al Di Meola, John McLaughlin, Ryo Kawasaki, and Frank Zappa, saxophonist Wayne Shorter and bassists Jaco Pastorius and Stanley Clarke. Jazz fusion was also popular in Japan, where the band Casiopea released over thirty fusion albums.

According to jazz writer Stuart Nicholson, "just as free jazz appeared on the verge of creating a whole new musical language in the 1960s ... jazz-rock briefly suggested the promise of doing the same" with albums such as Williams' Emergency! (1970) and Davis' Agharta (1975), which Nicholson said "suggested the potential of evolving into something that might eventually define itself as a wholly independent genre quite apart from the sound and conventions of anything that had gone before." This development was stifled by commercialism, Nicholson said, as the genre "mutated into a peculiar species of jazz-inflected pop music that eventually took up residence on FM radio" at the end of the 1970s.[168]

Jazz-funk

By the mid-1970s, the sound known as jazz-funk had developed, characterized by a strong back beat (groove), electrified sounds[169] and, often, the presence of electronic analog synthesizers. Jazz-funk also draws influences from traditional African music, Afro-Cuban rhythms and Jamaican reggae, notably Kingston bandleader Sonny Bradshaw. Another feature is the shift of emphasis from improvisation to composition: arrangements, melody and overall writing became important. The integration of funk, soul, and R&B music into jazz resulted in the creation of a genre whose spectrum is wide and ranges from strong jazz improvisation to soul, funk or disco with jazz arrangements, jazz riffs and jazz solos, and sometimes soul vocals.[170]

Early examples are Herbie Hancock's Headhunters band and Miles Davis' On the Corner album, which, in 1972, began Davis' foray into jazz-funk and was, he claimed, an attempt at reconnecting with the young black audience which had largely forsaken jazz for rock and funk. While there is a discernible rock and funk influence in the timbres of the instruments employed, other tonal and rhythmic textures, such as the Indian tambora and tablas and Cuban congas and bongos, create a multi-layered soundscape. The album was a culmination of sorts of the musique concrète approach that Davis and producer Teo Macero had begun to explore in the late 1960s.

Traditionalism in the 1980s

The 1980s saw something of a reaction against the fusion and free jazz that had dominated the 1970s. Trumpeter Wynton Marsalis emerged early in the decade, and strove to create music within what he believed was the tradition, rejecting both fusion and free jazz and creating extensions of the small and large forms initially pioneered by artists such as Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington, as well as the hard bop of the 1950s. It is debatable whether Marsalis' critical and commercial success was a cause or a symptom of the reaction against Fusion and Free Jazz and the resurgence of interest in the kind of jazz pioneered in the 1960s (particularly modal jazz and post-bop); nonetheless there were many other manifestations of a resurgence of traditionalism, even if fusion and free jazz were by no means abandoned and continued to develop and evolve.

For example, several musicians who had been prominent in the fusion genre during the 1970s began to record acoustic jazz once more, including Chick Corea and Herbie Hancock. Other musicians who had experimented with electronic instruments in the previous decade had abandoned them by the 1980s; for example, Bill Evans, Joe Henderson, and Stan Getz. Even the 1980s music of Miles Davis, although certainly still fusion, adopted a far more accessible and recognisably jazz-oriented approach than his abstract work of the mid-1970s, such as a return to a theme-and-solos approach.

Read Next page