Eradication of spontaneous malignancy by local immunotherapy

Great Space

Deliver locally, act globally

Mobilizing endogenous T cells to fight tumors is the goal of many immunotherapies. Sagiv-Barfi et al. investigated a combination therapy in multiple types of mouse cancer models that could provide sustainable antitumor immunity. Specifically, they combined intratumoral delivery of a TLR9 ligand with OX40 activation to ramp up T cell responses. This dual immunotherapy led to shrinkage of distant tumors and long-term survival of the animals, even in a stringent spontaneous tumor model. Both of these stimuli are in clinical trials as single agents and could likely be combined at great benefit for cancer patients.

Abstract

It has recently become apparent that the immune system can cure cancer. In some of these strategies, the antigen targets are preidentified and therapies are custom-made against these targets. In others, antibodies are used to remove the brakes of the immune system, allowing preexisting T cells to attack cancer cells. We have used another noncustomized approach called in situ vaccination. Immunoenhancing agents are injected locally into one site of tumor, thereby triggering a T cell immune response locally that then attacks cancer throughout the body. We have used a screening strategy in which the same syngeneic tumor is implanted at two separate sites in the body. One tumor is then injected with the test agents, and the resulting immune response is detected by the regression of the distant, untreated tumor. Using this assay, the combination of unmethylated CG–enriched oligodeoxynucleotide (CpG)—a Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9) ligand—and anti-OX40 antibody provided the most impressive results. TLRs are components of the innate immune system that recognize molecular patterns on pathogens. Low doses of CpG injected into a tumor induce the expression of OX40 on CD4+ T cells in the microenvironment in mouse or human tumors. An agonistic anti-OX40 antibody can then trigger a T cell immune response, which is specific to the antigens of the injected tumor. Remarkably, this combination of a TLR ligand and an anti-OX40 antibody can cure multiple types of cancer and prevent spontaneous genetically driven cancers.

INTRODUCTION

T cells that recognize tumor antigens are present in the tumor microenvironment, and their activity is modulated through stimulatory and inhibitory receptors. Once cancer is well established, the balance between these inputs is tipped toward immunosuppression (1, 2). The inhibitory signals on T cells are delivered through molecules such as cytotoxic T lymphocyte–associated protein 4 (CTLA4) and programmed cell death protein 1 (PD1) by interaction with their respective ligands expressed on cancer cells and/or antigen-presenting cells (APCs). However, these same tumor-reactive T cells express stimulatory receptors including members of the tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) superfamily. Therefore, many attempts are being made to relieve the negative checkpoints on the antitumor immune response and/or to stimulate the activation pathways of the tumor-infiltrating effector T cells (Teffs).

Here, we conducted a preclinical screen to identify candidate immunostimulatory agents that could trigger a systemic antitumor T cell immune response when injected locally into one site of tumor. We found that Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9) ligands induce the expression of OX40 on CD4 T cells in the tumor microenvironment. OX40 is a costimulatory molecule belonging to the TNFR superfamily, and it is expressed on both activated Teffs and regulatory T cells (Tregs). OX40 signaling can promote Teff activation and inhibit Treg function.

The addition of an agonistic anti-OX40 antibody can then provide a synergistic stimulus to elicit an antitumor immune response that cures distant sites of established tumors. This combination of TLR9 ligand and anti-OX40 antibody can even treat spontaneous breast cancers, overcoming the effect of a powerful oncogene. This in situ vaccine maneuver is safe because it uses low doses of the immunoenhancing agents and practical because the therapy can be applied to many forms of cancer without prior knowledge of their unique tumor antigens.

RESULTS

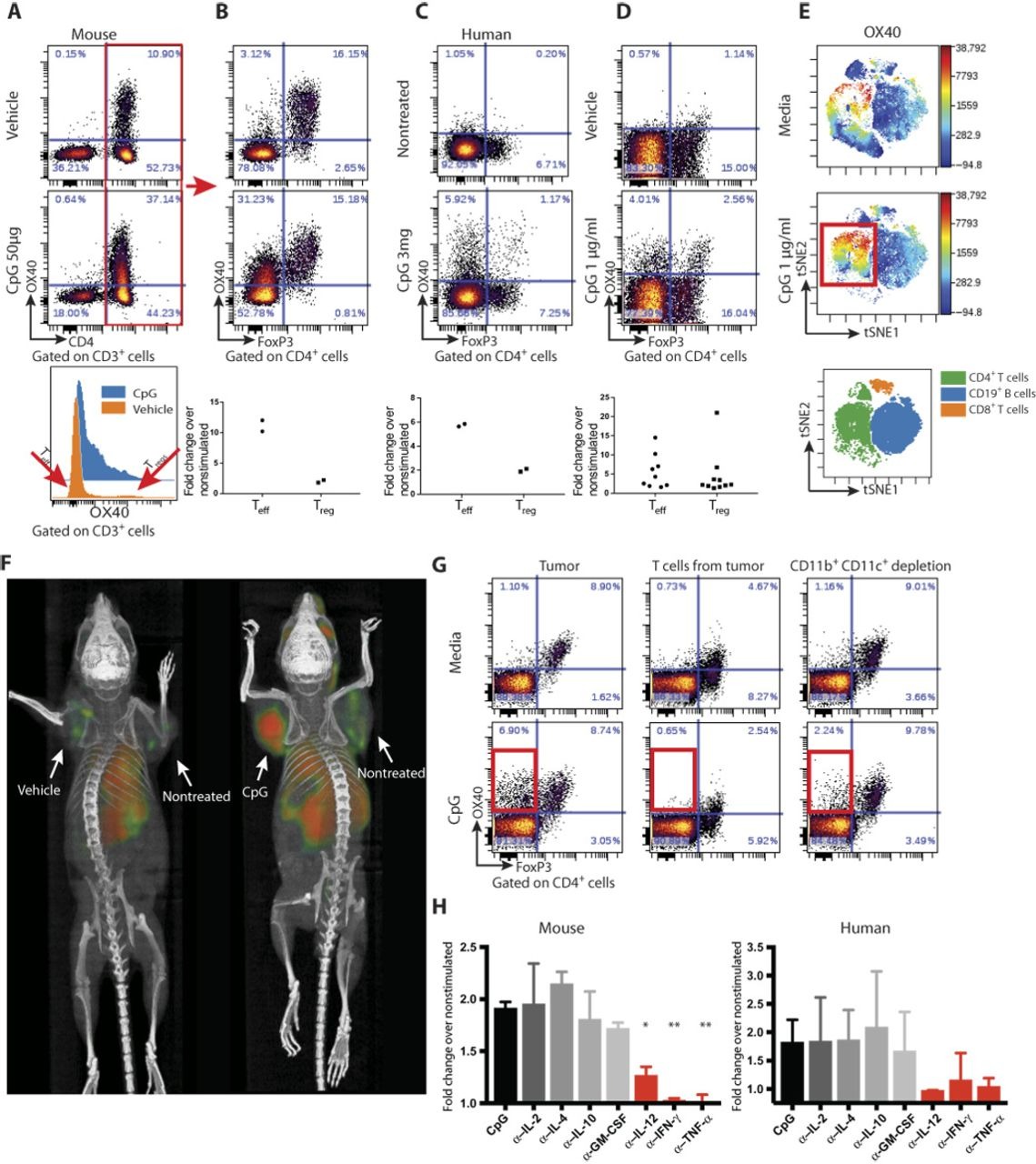

In situ vaccination with a TLR9 ligand induces the expression of OX40 on intratumoral CD4 T cells

TLRs are known to signal the activation of a variety of cells of the innate and adaptive immune system. To exploit this for cancer therapy, we subcutaneously implanted a tumor into syngeneic mice, and after the tumor had become established, we injected a CpG oligodeoxynucleotide—a ligand for TLR9—into the tumor nodule. We then analyzed the intratumoral T cells for their expression of inhibitory and activation markers. Before treatment, we observed that OX40 was expressed on CD4 cells in the tumor microenvironment (Fig. 1A, top) and that this was restricted mainly to the Tregs, as has been previously reported (3–5) (Fig. 1B, top). After intratumoral injection of CpG, there was up-regulation of OX40 on CD4 T cells (Fig. 1A, middle), mostly among the effector CD4 cells that greatly outnumber the Tregs (Fig. 1, A and B, bottom). This inductive effect was specific to the activating receptor OX40 and did not occur for inhibitory T cell checkpoint targets such as CTLA4 and PD1 (fig. S1A). Moreover, this OX40 up-regulation on CD4 cells also occurred in a patient with follicular lymphoma that had been treated with low-dose radiation and intratumoral injection of CpG (Fig. 1C) and in tumor-infiltrating cell populations from lymphoma patients’ samples that were exposed to CpG in vitro (Fig. 1, D and E, and fig. S2). In these human cases, the enhancement of OX40 expression was observed on both Teffs and Tregs (Fig. 1D). All of these changes occurred only in the tumor that was injected with CpG and not in the tumor at the untreated site (fig. S1B).

CpG induces the expression of OX40 on CD4 T cells.

(A) A20 tumor–bearing mice were treated either with vehicle (top) or CpG (middle). Forty-eight hours later, tumors were excised and a single-cell suspension was stained and analyzed by flow cytometry. (B) OX40 expression within the CD3+CD4+ subset was separately analyzed for FoxP3-negative [effector T cell (Teff)] and FoxP3-positive [regulatory T cell (Treg)] subsets. Fold changes of OX40+ cells were calculated according to their frequencies in the vehicle versus CpG treatment (n = 2). (C) Fine needle aspirates from CpG-injected and noninjected tumors of a follicular lymphoma patient were obtained 22 hours after treatment. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) plots of OX40 expression within the CD4+ subset after a 24-hour rest in media. Top: Nontreated lesion. Bottom: CpG-treated site (n = 2). (D) Single-cell suspensions from biopsy specimens of human lymphoma (five mantle cell lymphomas and five follicular lymphomas) were exposed in vitro to CpG for 48 hours and analyzed for OX40 expression as in (B). (E) CpG-stimulated human lymphoma–infiltrating CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, and CD19+ B cells were gated and visualized in tSNE (t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding) space using Cytobank software. The viSNE map shows the location of each CD4+, CD19+, and CD8+ cell population (green, blue, and orange, respectively; bottom). Cells in the viSNE maps were colored according to the intensity of OX40 expression. CpG up-regulation of OX40 expression on a subset of CD4+ T cells is highlighted by a red box. (F) BALB/c mice were implanted subcutaneously with A20 lymphoma cells (5 × 106) on both the right and left shoulders. When tumors reached between 0.7 and 1 cm in the largest diameter (typically on days 8 to 9 after inoculation), phosphate-buffered saline and CpG (50 μg) were injected into one tumor site (left tumor). Sixteen hours later, 64Cu-DOTA-OX40 was administered intravenously via the tail vein. Positron emission tomography imaging of mice was performed 40 hours after in situ treatment. Left: Vehicle-treated. Right: CpG-treated. These images are representative of six mice per group. (G) Fresh A20 tumors were excised from animals (typically 5 to 6 days after inoculation), and either whole tumors (left), T cells purified from the tumor (middle), or whole tumor depleted of CD11b- and CD11c-expressing cells (right) were treated for 48 hours with media (top) or CpG (bottom) and were analyzed for their expression of OX40 by flow cytometry. (H) Left: A20 tumors were excised as in (F). Right: Single-cell suspensions from biopsy specimens of human follicular lymphoma. Tumors were treated for 48 hours with media and CpG with or without antibodies (1 μg/ml) to interleukin-2 (IL-2), IL-4, IL-10, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), IL-12, interferon-γ (IFN-γ), or tumor necrosis factor–α (TNF-α) and were analyzed for their expression of OX40 by flow cytometry. α–IL-12, *P = 0.0144; α–IFN-γ, **P = 0.0032; α–TNF-α, **P = 0.008, unpaired t test, either depleting antibody versus CpG alone.

CpG induces OX40 as revealed by in vivo imaging. The enhancement of OX40 expression by intratumoral injection of CpG could be visualized in mice by whole-body small-animal positron emission tomography (PET) imaging after tail-vein administration of an anti-OX40 antibody labeled with 64Cu (Fig. 1F). Remarkably, the systemically injected antibody revealed that OX40 was induced in the microenvironment of the injected tumor, as opposed to a second noninjected tumor site in the same animal. This result indicates that the effect of CpG at this low dose to up-regulate OX40 expression is predominately local.

CpG induces cytokine secretion by myeloid cells which in turn induces OX40 expression on T cells. Purified tumor-infiltrating T cells do not up-regulate OX40 when exposed to CpG in vitro (Fig. 1G). The T cells within whole tumor cell populations similarly fail to up-regulate OX40 after depletion of macrophages and dendritic cells (Fig. 1G). From these results, we conclude that myeloid-derived cells communicate the CpG signal to T cells. Therefore, we tested for the role of several cytokines in this cellular cross-talk. In human and mice tumors, antibody neutralization of interleukin-12 (IL-12), interferon-γ (IFN-γ), and TNF-α each prevented the CpG-induced up-regulation of OX40 on T cells in these tumor cell populations (Fig. 1H). In contrast, neutralization of IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) had no effect (fig. S3).

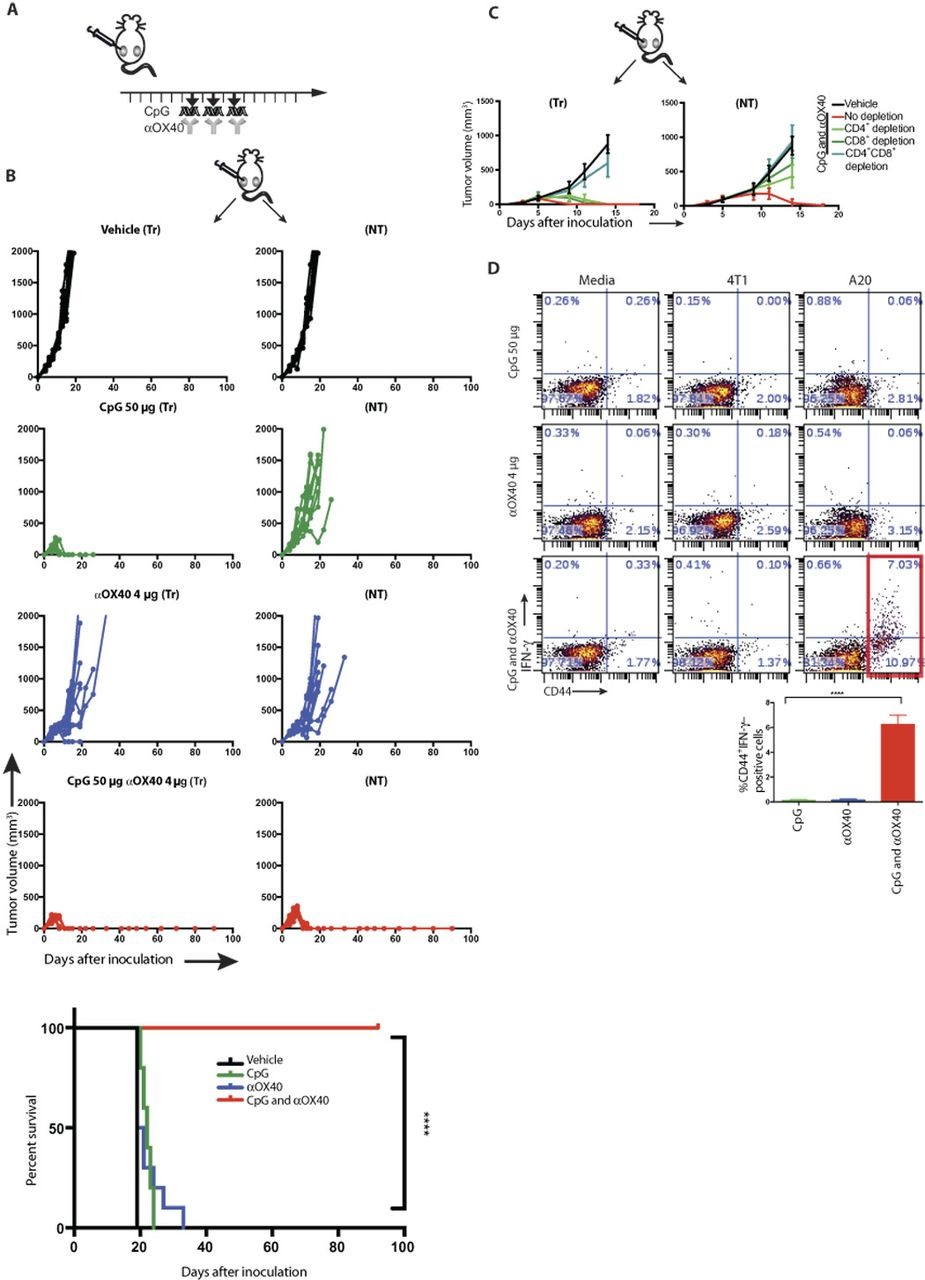

In situ vaccination with a TLR ligand and anti-OX40 antibody induces T cell immune responses that cure established cancers

On the basis of the results above, we hypothesized that an agonistic anti-OX40 antibody could augment CpG treatment and help to induce antitumor immune responses. To test this hypothesis, we implanted mice with A20 B cell lymphoma tumors at two different sites in the body, allowed the tumors to become established, and then injected a TLR agonist together with a checkpoint antibody into only one tumor site (Fig. 2A). The animals were then monitored for tumor growth at both the injected and the distant sites (Fig. 2B). The tumors of vehicle-treated mice grew progressively at both sites. CpG caused complete regression of tumors at the local injected site but had only a slight delay in growth of the distant nontreated tumor. The anti-OX40 antibody alone induced a slight delay in growth of both the treated and nontreated tumors. However, the combination of CpG and anti-OX40 resulted in complete regression of both injected and noninjected tumors. Consistent with the time needed to induce an adaptive T cell response, the kinetics of regression at the two sites was different, with the distant site following the local site by several days (fig. S1C). Tumor regressions in response to the combined treatment were long-lasting and led to cure of most of the mice (Fig. 2B, bottom).

In situ vaccination of CpG in combination with anti-OX40 antibody cures established local and distant tumors.

(A) Treatment schema. BALB/c mice were implanted subcutaneously with A20 lymphoma cells (5 × 106) on both the right and left sides of the abdomen. When tumors reached between 0.5 and 0.7 cm in the largest diameter (typically on days 4 to 5 after inoculation), αOX40 (4 μg) and CpG (50 μg) were injected into one tumor site every other day for a total of three doses. Tumors sizes were serially measured with a caliper. (B) Tumor growth curves. Left column: Treated tumors (Tr). Right column: Nontreated tumors (NT). Top to bottom: Vehicle, CpG, αOX40, and CpG and αOX40 and survival plots of the treated mice (n = 10 mice per group). ****P < 0.0001, unpaired t test. Shown is one representative experiment out of nine. (C) Effect of CD4/CD8 depletion. Mice were implanted with bilateral tumors, and one tumor was injected with CpG and αOX40 antibody according to the schema in (A). CD4 (0.5 mg)–and CD8 (0.1 mg)–depleting antibodies were injected intraperitoneally on days 6, 8, 12, and 15 (n = 10 mice per group). (D) CD8 T cell immune response. Splenocytes from the indicated groups obtained on day 7 after treatment were cocultured with media, 1 × 106 irradiated 4T1 cells (unrelated control tumor), or A20 cells (homologous tumor) for 24 hours. Intracellular IFN-γ was measured in CD8+ T cells by flow cytometry as a percentage of CD44hi (memory CD8) T cells shown in dot plots and bar graph, summarizing data from three experiments (n = 9 mice per group). ****P < 0.0001, unpaired t test.

The systemic antitumor response required the presence of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells because mice treated with the corresponding depleting antibodies were unable to control tumor growth (Fig. 2C). CD8+ T cells derived from mice treated with both CpG and anti-OX40 antibody responded to tumor cells in vitro as measured by IFN-γ production (Fig. 2D). CD4+ T cells from mice treated by the combination also responded to tumors in vitro but with a lesser magnitude (fig. S4). Immediately after CpG and anti-OX40 injection, the proportion of the CD4 effector/memory T cell subset increased at the treated site. Twenty-four hours later, this subset increased in the spleen, and 5 days later, the same occurred at the distant, nontreated site (fig. S5).

Distant tumors occasionally did recur in mice treated with the effective combination (3 of 90 mice), and interestingly, these late recurring tumors were sensitive to retreatment by anti-OX40 and CpG (fig. S6). An alternative TLR agonist, resiquimod (R848), a ligand for TLR7/8, in combination with anti-OX40 induced a similar systemic antitumor immune response (fig. S7A). Anti-OX40 antibody was especially effective compared to other immune checkpoint antibodies, such as anti-PD1 and anti–PDL1 (programmed death-ligand 1) (fig. S7B), which delayed tumor growth in the nontreated site but were not curative.

In situ vaccination with CpG and anti-OX40 was effective not only against lymphoma but also against tumors of a variety of histologic types, such as breast carcinoma (4T1), colon cancer (CT26), and melanoma (B16-F10) (fig. S8, A to C). In all these tumor models, the systemic therapeutic effects were induced by extremely low doses of both the CpG (typically 50 μg) and the anti-OX40 antibody (typically 8 μg) or even lower (fig. S9). However, the TLR agonist worked best when it was injected directly into the tumor, consistent with its action to up-regulate the OX40 target in the T cells of the tumor microenvironment. Similar systemic effects were obtained when the OX40 antibody was given systemically, rather than into the tumor, but at higher doses (fig. S10).

In situ vaccination protects animals genetically prone to spontaneous breast cancers

Female FVB/N-Tg(MMTV-PyVT)634Mul/J mice (also known as PyVT/PyMT) develop highly invasive mammary ductal carcinomas that give rise to a high frequency of lung metastases (6). By 6 to 7 weeks of age, all female carriers develop the first palpable mammary tumor (7), and eventually, tumors develop in all of their 10 mammary fat pads. This provided an opportunity for therapeutic intervention in a spontaneous tumor model where the site of tumor development is known and accessible for in situ vaccination.

Young mice were observed, and as their first tumor reached 50 to 75 mm3, we injected it with CpG and anti-OX40 antibody (Fig. 3A). In some cases, a second tumor was present at the beginning of therapy, and in these mice with coincident tumors, treatment at a single tumor site with CpG and anti-OX40 led to significant retardation of growth of the contralateral tumor (Fig. 3B), establishing the combination as a therapy for established and disseminating tumors. The injected and the noninjected tumors regressed, and remarkably, the treated mice were protected against the occurrence of independently arising tumors in their other mammary glands (Fig. 3C). The treated mice had significantly lower eventual total tumor burdens (Fig. 3, C and D) and developed far fewer lung metastases (Fig. 3E). This in situ vaccination with CpG and anti-OX40 not only caused tumor regression and reduced tumor incidence but also had a major effect on the survival of these cancer-prone mice (Fig. 3F). After CpG and anti-OX40 treatment, these mice developed antitumor CD8 T cells in their spleens as indicated by their ability to produce IFN-γ when exposed in vitro to autologous tumor cells from the noninjected tumor site (Fig. 3G). These results establish that the antitumor immune response was elicited against tumor antigens shared by all the independently arising tumors in these mice, rather than antigens unique to the injected tumor, and accounted for the impressive therapeutic effects seen.

In situ vaccination with CpG and anti-OX40 is therapeutic in a spontaneous tumor model.

(A) MMTV-PyMT transgenic female mice were injected into the first arising tumor (black arrow) with either vehicle (top) or with CpG and αOX40 (bottom); pictures were taken on day 80. (B) CpG and αOX40 decrease the tumor size of a nontreated contralateral tumor. Growth curves represent the volume of a contralateral (untreated) tumor in mice that had two palpable tumors at the beginning of treatment. Mice treated by in situ vaccination (red; n = 6) or vehicle (black; n = 6). ***P = 0.0008, unpaired t test. (C) CpG and αOX40 decrease the total tumor load. Growth curves represent the sum of the volume of 10 tumors from the different fat pads of each mouse, measured with calipers (n = 10 mice per group), and the window of treatment is indicated by the gray bar. ****P < 0.0001, unpaired t test. (D) Time-matched quantification of the number of tumor-positive mammary fat pads. **P = 0.011, unpaired t test (n = 9 mice per group). (E) Mice were sacrificed at the age of 80 days, and lungs were excised and analyzed ex vivo for the number of metastases (mets). ****P < 0.0001, unpaired t test (n = 10 mice from vehicle-treated group; n = 9 mice with CpG and αOX40). (F) Survival plots of the treated mice. ****P < 0.0001. Data are means ± SEM (n = 10 mice per group). (G) CD8 T cell immune response. Splenocytes from the indicated groups obtained on days 7 to 15 after treatment were cocultured for 24 hours with either media or 1 × 106 irradiated tumor cells taken from an independent contralateral site on the body. Intracellular IFN-γ was measured in CD8+ T cells by flow cytometry as shown in dot plots and bar graph, summarizing data as a percentage of CD44hi (memory CD8) T cells (n = 3 mice per group).

Therapeutic effect of in situ vaccination is antigen-specific and triggered at the site of local injection

The results of cross-protection against independently arising tumors in the spontaneous breast cancer model raise the question of antigen specificity. We approached this question using two different tumors that are antigenically distinct. Mice cured by in situ vaccination of the A20 lymphoma were immune to rechallenge with the same tumor (A20) but not to a different tumor (CT26) (fig. S11). Conversely, mice cured of the CT26 tumor were immune to rechallenge with CT26 but not with A20. Therefore, these two tumors are antigenically distinct.

To further demonstrate the specificity of the antitumor response, we implanted tumors into mice at three different body sites: two with the A20 and one with CT26 (Fig. 4A). One A20 tumor site was then injected with CpG and anti-OX40 antibody. Both A20 tumors, the injected one and the noninjected one, regressed but the unrelated CT26 tumor continued to grow (Fig. 4A). In a reciprocal experiment, we injected mice with two CT26 tumors and one A20 tumor and treated one CT26 tumor. Once again, only the homologous distant tumors (in this case, CT26) regressed but not the unrelated A20 tumor (Fig. 4B). This result confirmed that the immune response induced by the therapy was tumor-specific. Furthermore, it demonstrated that in situ vaccination with these low doses of agents works by triggering an immune response in the microenvironment of the injected site rather than by diffusion of the injected agents to systemic sites.

Immunizing effects of intratumoral CpG and anti-OX40 are local and tumor-specific.

(A) Three-tumor model. Each mouse was challenged with three tumors, two of them A20 lymphoma (blue) and one CT26 colon cancer (red). Mice were treated at the indicated times (black arrows). Tumor growth curves of the treated tumor (bottom left), the homologous nontreated A20 tumor (top right), and the heterologous CT26 tumor (bottom right). Photos of a representative mouse at day 11 after tumor challenge from the vehicle-treated group and from the group with A20 tumors treated with intratumoral CpG and αOX40 (n = 10 mice per group) are shown. (B) Reciprocal three-tumor model with two CT26 tumors and one A20 tumor. Treatment was given to one CT26 tumor, and growth curves are shown for the treated CT26 tumor site (bottom right), the nontreated homologous CT26 tumor site (top right), and the heterologous A20 tumor (bottom right). Photos of a representative mouse from this experiment (n = 10 mice per group) are shown. (C) Mixed three-tumor model. Each mouse was challenged with three tumors: one A20 (blue, top right abdomen), one CT26 (red, bottom right abdomen), and one mixture of A20 and CT26 tumor cells (blue and red gradient, left abdomen). Mice were treated only in the mixed tumor at the indicated times (black arrows). Tumor growth curves of the treated tumor (bottom left), the nontreated A20 tumor (top right), and the nontreated CT26 tumor (bottom right). Photos of a representative mouse at day 11 after tumor challenge from the vehicle-treated group (top) and at day 17 from the intratumoral CpG and αOX40 (n = 8 mice per group) are shown.

Naturally arising tumors can show intratumoral antigenic heterogeneity. To test whether CpG and anti-OX40 treatment can trigger an immune response against multiple different tumor antigens at the same time, we injected mice with a mixture of A20 and CT26 tumor cells at one site, treated that site with local CpG and anti-OX40 antibody, and monitored two additional sites of tumor containing each of the single tumor cells (A20 and CT26, respectively). In situ vaccination of the mixed tumor site simultaneously induced immune responses protective of each of the respective other two pure tumor sites (Fig. 4C). These results demonstrate the power of in situ vaccination to simultaneously immunize against a panoply of different tumor antigens.

Fc competency is required for efficacy of the anti-OX40 antibody

OX40 is expressed on both intratumoral FoxP3+ Tregs and activated Teffs (Fig. 1B). The immunoenhancing activity of the anti-OX40 antibody could therefore be mediated by inhibition/depletion of Tregs, by stimulation of Teffs, or by a combination of both. We tested the anti-OX40 Treg depletion hypothesis by replacing it with an antibody against folate receptor 4 (FR4), a Treg-depleting agent (fig. S12A) (8). Tregs were partially depleted (43% reduction) by the anti-FR4 in combination with CpG, but no distant therapeutic effect occurred (Fig. 5A). We further investigated this question using mice genetically engineered to express diphtheria toxin under the FoxP3 promoter (9, 10). Injection of diphtheria toxin led to complete Treg depletion in these mice (fig. S12B). However, when combined with intratumoral CpG, no distant therapeutic effect was observed (Fig. 5B). As others have shown, stimulation of Tregs through OX40 can impair their function (4, 11, 12), which we confirm here (fig. S13, A and B). Therefore, we conclude that Tregstimulatory impairment but not depletion is involved in the mechanism of therapeutic synergy with CpG. To dissect the mechanism of these potent therapeutic effects, we compared two different forms of the anti-OX40 antibody that differ in their ability to bind to CD16: the activating Fc receptor on natural killer (NK) cells and macrophages. When used in combination with CpG, the native, Fc-competent version of anti-OX40 antibody induced systemic antitumor immunity, whereas the Fc-mutant version did not (Fig. 5A). We repeated the in situ vaccination experiment in mice deficient in the Fc common γ chain, a component of the activating Fc γ receptors I, III, and IV (13). Once again, in the absence of Fc receptor interaction, this time at the level of the host, the effect of in situ vaccination with CpG and anti-OX40 antibody was lost (fig. S14). These results could implicate ADCC (antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity) function of the antibody or alternatively an Fc-dependent agonistic action of the anti-OX40 antibody (14, 15).

A competent Fc is required for the antitumor immune response.

(A and B) Effect of Treg depletion. (A) Tumors were implanted according to the schema in Fig. 2A. Mice were treated with either CpG and anti–folate receptor 4 (FR4) antibody (15 μg) or CpG and αOX40 as described in Fig. 2A, and the NT was measured over time. ****P < 0.0001, unpaired t test (n = 10 mice per group). (B) DEREG mice were implanted with B16-F10 melanoma cells (0.05 × 106) on both the right and left sides of the abdomen. Diphtheria toxin (DT; 1 μg) was injected intraperitoneally on days 1, 2, 7, and 14. CpG or combination of CpG and anti-OX40 was given on days 7, 9, and 11. The NT was measured over time. *P = 0.0495, unpaired t test (n = 4 mice per group). (C) A20 cells were inoculated and treated as described in Fig. 2A, tumor volumes were measured after treatment of CpG with either αOX40 rat immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) (red) or αOX40 rat IgG1 Fc mutant (black). ****P < 0.0001, unpaired t test (n = 10 mice per group). WT, wild type. (D) Tumors from control and treated mice were excised at the indicated times after a single treatment, and the cell populations from the different groups were differentially labeled (barcoded) with two different levels of violet tracking dye (VTD) and mixed together, stained, and analyzed as a single sample [n = 3 mice per group (C to F)]. (E to H) Dot plots for single time point and bar graphs for replicates of multiple time points. (E) Number of F4/80 CD11b+ myeloid cells. **P = 0.009 (8 h), Fc WT versus vehicle. (F) CD137 expression on natural killer (NK) cells. **P = 0.0035 (2 h), *P = 0.0343 (8 h), unpaired t test, Fc WT versus Fc mutant. (G) CD69 expression on CD8+ T cells. *P = 0.025 (8 h), **P = 0.0064 (24 h), unpaired t test, Fc WT versus Fc mutant. (H) Treg cell proliferation. ***P = 0.0003 (24 h), unpaired t test, Fc WT versus Fc mutant.

Therefore, we examined immune cells in the tumor microenvironment during the early phases of treatment with intratumoral CpG and compared the changes induced with the Fc-competent to those induced by the Fc-mutant version of the anti-OX40 antibody. Early after in situ vaccination, within 24 hours, the tumor-infiltrating cell populations from animals treated with Fc-competent or Fc-mutant antibodies were barcoded (16), pooled, and then costained by a panel of antibodies to identify subsets of immune cells and their activation states (Fig. 5B). The cell populations derived from the different treatment groups were then separately identified by their barcodes. In response to the anti-OX40 antibody with the native Fc, there was an increase in myeloid cell infiltration (Fig. 5C), a cell population important in the cross-talk between CpG and the T cells (see above; Fig. 1, F and G). NK cells showed an Fc-dependent up-regulation of their CD137 activation marker (Fig. 5D). In addition, the Fc-competent but not the Fc-mutant antibody induced activation of a population of CD8 T cells, as indicated by increased CD69 expression (Fig. 5E). Tregs were inhibited in their proliferation by comparison to those exposed to the antibody with the mutated Fc region (Fig. 5F). Neither Tregs nor Teffs were killed by the Fc-competent antibody (fig. S15). These early cellular changes occurred only in the tumor microenvironment of the treated site and were not evident at other sites throughout the mouse (fig. S1B). These results imply that anti-OX40 antibodies, in conjunction with TLR ligands, can induce therapeutic systemic antitumor immune responses by a combination of NK cell activation, Treg inhibition, and Teff activation, all at the treated tumor site.

View full information - http://stm.sciencemag.org/content/10/426/eaan4488.full

Perhaps this is the most important discovery in medicine of the 21st century. We are waiting for further tests.