Private Address Ablk Rfc1918 Iana Reserved

⚡ 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 INFORMATION AVAILABLE CLICK HERE 👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

University Information

Technology Services

Services Toggle Services navigation

Initiatives Toggle Initiatives navigation

Get Help Toggle Get Help navigation

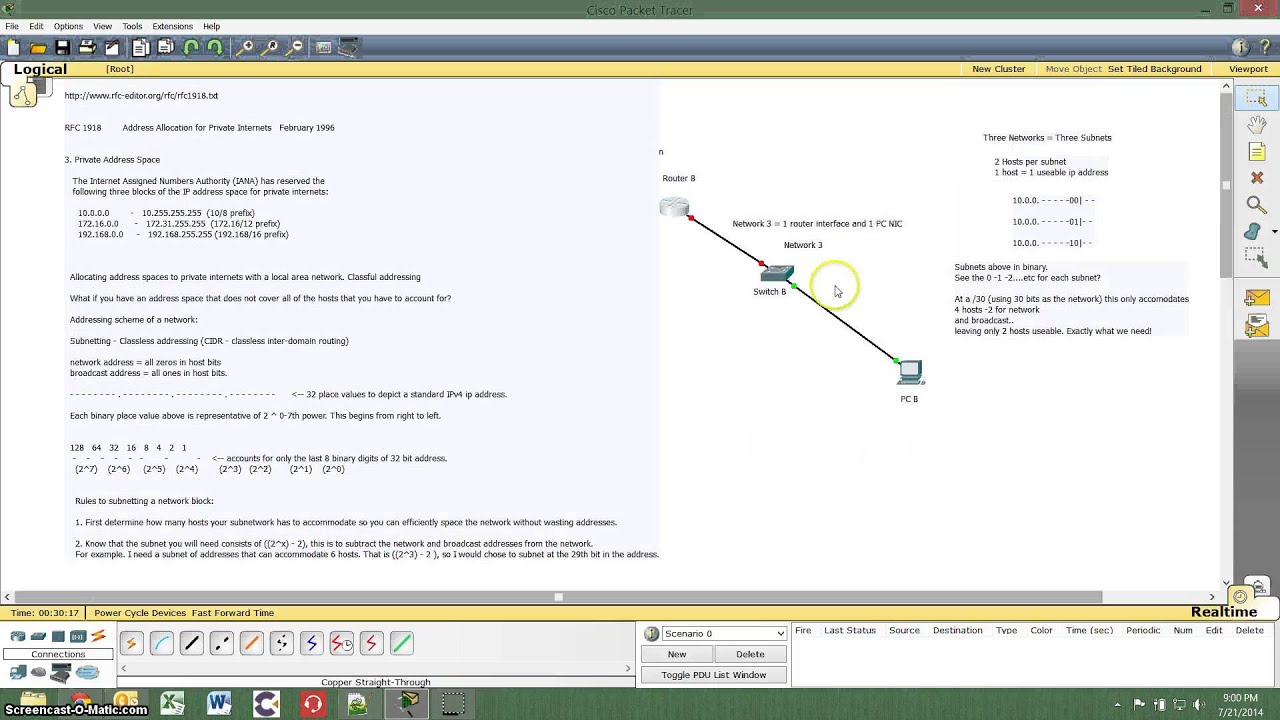

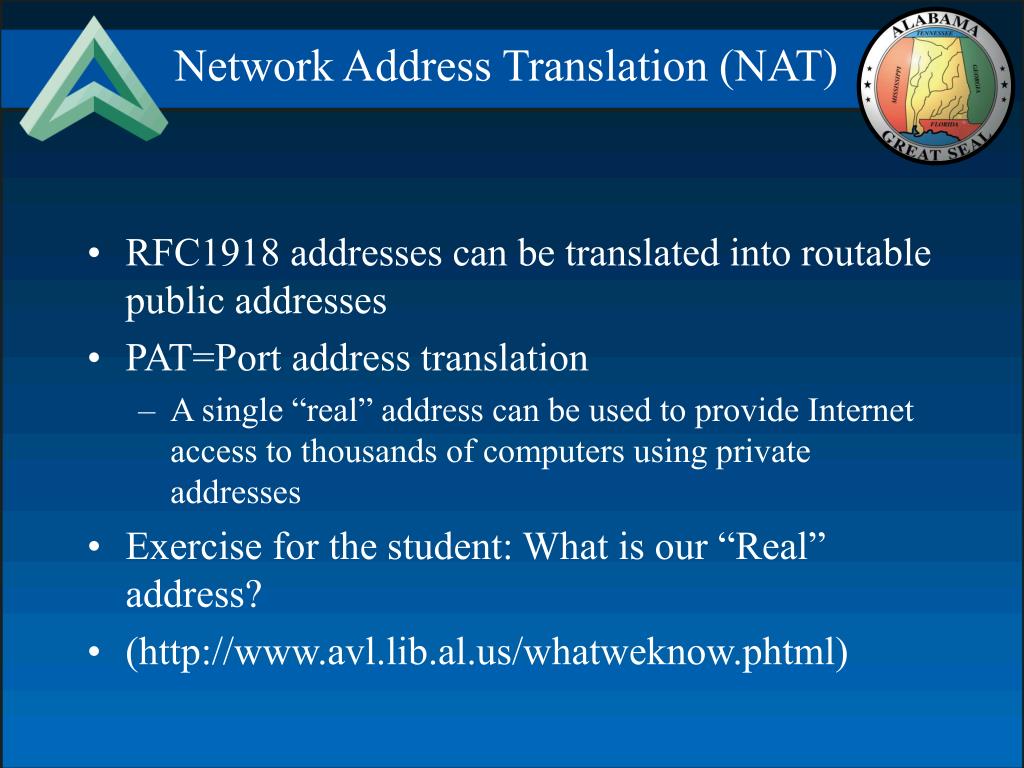

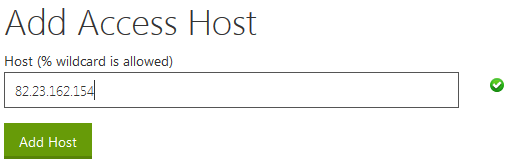

Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) has reserved certain IP addresses as private addresses for use with internal websites or intranets. These are also referred to as RFC 1918 addresses. These addresses are not routable on the public internet, but are meant for devices that reside behind a router or other Network Address Translation (NAT) device or proxy server. Private IP addresses are used either to hide systems from the public internet or to provide an additional range of addresses to organizations that do not have sufficient public IP addresses to distribute on their network. Organizations can use these numbers to assign internal IP addresses without having to worry about an IP address conflict or having to obtain a new block of IP addresses.

If you connect to the internet as a home user with a residential router, you will typically benefit from this arrangement. Although you may be paying for only one IP address through your internet service provider (ISP), you can have unlimited devices connected to the internet. Using a private IP address will make your computer invisible to certain types of network attacks; however, you will not be able to easily establish your computer as a server.

At Indiana University, private IP addresses are used for several purposes:

It is very important that private addresses used within an organization do not conflict with each other. Since back-nets are available only to the locally connected servers, not to any other computers on campus, the private IP addresses used for two different back-nets can be the same, but they cannot conflict with other private IP addresses on campus.

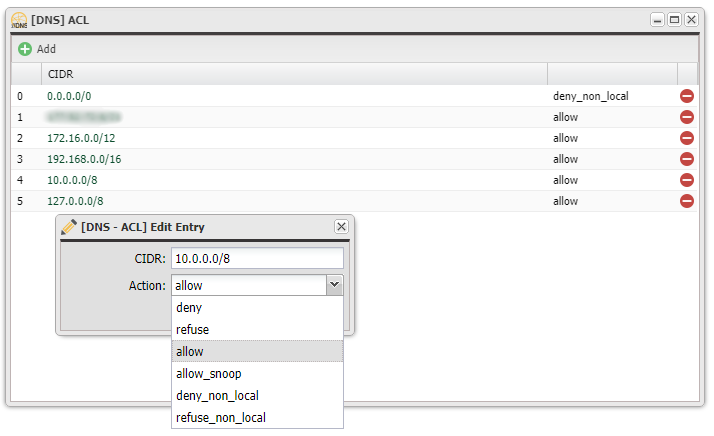

Therefore, UITS has designated the 10.0.0.0/8 private address block to assign to devices that need to be reachable across campus, but not on the internet. 192.168.0.0/16 is designated for private back-nets available only to locally connected computers and not to the rest of the IU network.

Addresses in the range 169.254.0.0/16 are auto-assigned by a host (to itself) if it is not configured with a static IP and is unable to obtain a DHCP lease. As these addresses are auto-assigned, they should not be used for private networks and should not be statically configured on hosts.

This is document aijr in the Knowledge Base.

Last modified on 2020-01-27 13:13:21.

We receive many reports of spam, apparent hacker activity, and other forms of abuse. Most frequently, people make these reports because they have found an Internet address associated with the abusive activity, and through a bit of research, they find the IANA name associated in some way with that address.

In virtually all such cases, the association of the IANA name with a particular address is not actually useful in dealing with the abuse incident. IANA is a set of record-keeping functions we provide, it is not an ISP, and we have no control over the use of any Internet Protocol (IP) addresses except the very few that are directly tied to the iana.org domain name.

This document was written to explain our role and to provide some pointers that may be useful in actually resolving abuse cases.

The word "authority" in the IANA name is perhaps a bit misleading: it means that the IANA service keeps authoritative records concerning various numbers for other organizations; the choice of what goes into these records is determined by a variety of engineering and other considerations. We serve as a book-keeper in recording the assignments that are made. In Internet terminology, the record-keeping service we perform is called a registration service, and we serve as a registry.

In addition to IP addresses, we also serve as a registry for a variety of Protocol Numbers (see http://www.iana.org/numbers/ and several other kinds of names and identifiers.

It is important to realize that we are not an ISP in any way, and we do not provide any network services to any end users or organizations. We do not control the use of any of the numbers it records, nor, in general, do we have the authority to change the values we record.

IP addresses are numbers. Currently there are two types of IP addresses in active use: IP version 4 (IPv4) and IP version 6 (IPv6). IPv4 was initially deployed on 1 January 1983 and is still the most commonly used version.

IPv4 addresses are 32-bit numbers that range from 0 to 4,294,967,295 but they are almost never used or seen in that form. Instead, they are usually represented by the familiar "dotted decimal" notation, with four decimal numbers separated by periods, for example, 192.0.2.80 or 203.0.13.25. Each individual number in a dotted decimal ranges in value from 0 to 255, and thus, in dotted decimal notation, IP addresses range from 0.0.0.0 to 255.255.255.255.

Given that there are over 4 billion individual IPv4 addresses, in many circumstances it is impractical to deal with them individually, and instead one deals with ranges (or "blocks") of IPv4 addresses. For example, one may be interested in the range of 256 IPv4 addresses from 192.168.51.0 to 192.168.51.255.

Deployment of the IPv6 protocol began in 1999. IPv6 addresses are 128-bit numbers and are conventionally expressed using hexadecimal strings (for example, 2001:db8::abc:587).

We maintain a high-level registry of IP addresses. It works with the Regional Internet Registries (RIRs) to distribute the large blocks of IP addresses among the RIRs. There are currently five RIRs, distributed around the world:

The RIRs are the organizations that actually allocate IP addresses to ISPs. These allocations are in smaller blocks of addresses. The web page "Internet Protocol v4 Address Space" documents how the IPv4 address space is distributed among the RIRs.

Many of the IP address blocks in our registry are allocated to the RIRs. For example, consider the following line from the page referenced above:

This means that the IP address block of 123.0.0.0-123.255.255.255 was allocated to APNIC in January 2006. If you are having problems with an IP address that is part of this block, you should go to APNIC's WHOIS service at "whois.apnic.net" (see below for details) to find out who has been assigned that address.

We keep this top-level list for all of the IPv4 addresses. This includes:

Special-use IP addresses are marked as registered to IANA so that they are reserved for the special use on behalf of the Internet community. This does not mean that the special-use addresses are "used" by us (see further explanation below). Only a very small block of IPv4 addresses (192.0.32.0 to 192.0.47.255) has been "assigned" to us for our operations. Only Internet traffic from this range actually originates from our network.

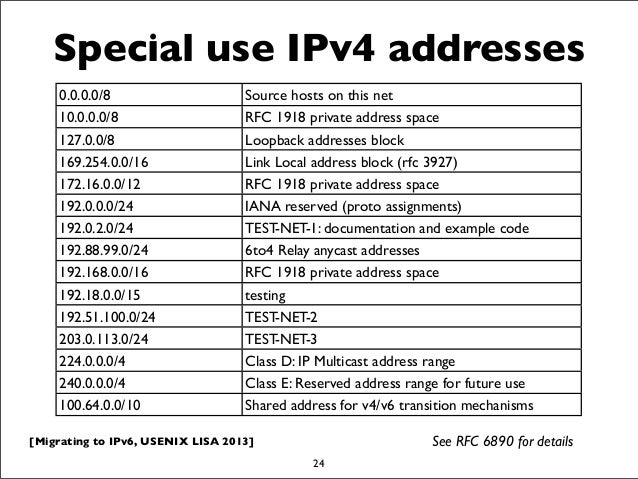

Several address ranges are reserved for "Special Use". These addresses all have restrictions of some sort placed on their use, and in general should not appear in normal use on the public Internet. The overview below briefly explains the purpose of these addresses – in general they are used in specialized technical contexts. They are described in more detail in RFC 6890.

These address blocks are reserved for use on private networks, and should never appear in the public Internet. There are millions of private networks (for example home firewalls often use them). People can use these address blocks without informing us, so we have no record of who uses which of these addresses.

The point of private address space is to allow many organizations in different places to use the same addresses, and as long as these disconnected or self-contained islands of IP-speaking computers (private networks) are not connected, there is no problem. If you see an apparent attack, or spam, coming from one of these address ranges, then either it is coming from your local environment, your ISP, or the address has been "spoofed".

The Private addresses are documented in RFC 1918. If you have further questions about RFC 1918 usage, please contact your ISP.

Addresses in the range 169.254.0.0 to 169.254.255.255 are used automatically by most network devices when they are configured to use IP, do not have a static IP Address assigned and are unable to obtain an IP address using DHCP.

This traffic is intended to be confined to the local network, so the administrator of the local network should look for misconfigured hosts. Some ISPs inadvertently also permit this traffic, so you may also want to contact your ISP. This is documented in RFC 6890.

Each computer on the Internet uses 127.0.0.0/8 to identify itself, to itself. 127.0.0.0 to 127.255.255.255 is earmarked for what is called "loopback". This construct allows a computer to confirm that it can use IP and for different programs running on the same machine to communicate with each other using IP. Most software only uses 127.0.0.1 for loopback purposes (the other addresses in this range are seldom used). All of the addresses within the loopback address are treated with the same levels of restriction in Internet routing, so it is difficult to use any other addresses within this block for anything other than node specific applications, generally bootstraping. This is documented in RFC 6890.

The IPv4 Address Registry and the Whois use the word unallocated (sometimes "reserved") to mean that the addresses are reserved for future allocation. No one should be using these addresses now. These addresses will be assigned for use in the public Internet in the future. If addresses are needed for private networks then the private-use addresses mentioned above should be used.

Addresses in the range 224.0.0.0 to 239.255.255.255 are set aside for the special purpose of providing multicast services in the Internet. Multicast services allow a computer to send a single message to many destinations. Examples include the software that keeps computers’ clocks synchronised and television services delivered over IP, typically by cable ISPs. Various addresses in this range are used by routers and others are used by hosts that are listening to multicast sessions.

These addresses are available for any host that wants to participate in multicast, and typically are assigned dynamically. The source address should not be multicast (without prior agreement). The destination address may be multicast. For technical background information please see RFC 1112 and RFC 2236.

If you encounter an IPv4 address that does not fit any of the above categories, researching the various information sources to find a person responsible for an IP address may be a challenge. Moreover, even if such a person is found, they may well be halfway around the world, and not share your language or your legal system. Nonetheless, you must decide if it is worth the effort to try. This section outlines the procedure one should follow in finding the contact information for a responsible person.

Step 1 - Look up the IP address in the Regional Internet Registries (RIRs) "whois" servers.

By using the "Whois" service, look up the IP address in all five Regional Internet Registries or RIRs.

If one of the RIRs’ Whois servers does not have information about the IP address you are inquiring about, try the others.

If the RIR WHOIS says the IP address is registered to IANA, make sure you try the other RIRs to verify that they also say the IP addresses are registered to the IANA as some of the RIRs databases may not have caught the latest delegations to other RIRs.

Step 2 - If all RIRs list an address as assigned to IANA, you should check to see if this address is for "Special Use" or if it is "Unallocated" ("Reserved").

If the address that you are inquiring about does not have contact information in one of the RIRs, is not mentioned in the explanations above, or you have further questions, please send an e-mail to abuse-filter@iana.org so that we may look into the problem further.

See below for additional information about fabricated IP addresses and the blackhole servers.

It is quite possible that an IP address in an e-mail header could be fabricated.

E-mail protocols are not secure and anyone with the minor technical skills necessary can forge any part of an e-mail. Forgeries are generally trivial to identify. We cannot locate the individuals who forge e-mail headers. In fact, return addresses can be spoofed right down to the packet level. (Just like in postal mail, one can put pretty much anything as a return address, but if there is a problem with the "to" address, the letter can't be delivered.) IP addresses can be spoofed in protocols other than e-mail, as well.

Please see the following 8 questions/answers for information regarding the "blackhole" servers:

Q1: What are the blackhole servers?

A1: The "blackhole" Servers, "blackhole-1.iana.org" and "blackhole-2.iana.org", are an obscure part of the Internet infrastructure. People are sometimes puzzled or alarmed to find unexplained references to them in log files or other places. This FAQ tries to explain what these servers do, and why you may be seeing them. Specifically, these servers are part of the Domain Name System (DNS), and respond to inverse queries to addresses in the the reserved RFC 1918 address ranges:

These addresses are reserved for use on private intranets, and should never appear on the public internet. The 192.168.0.0 addresses are especially common, being frequently used in small office or home networking products like routers, gateways, or firewalls.

A2. "prisoner" is a blackhole server. A help document, “I'm Being Attacked by PRISONER.IANA.ORG!” has been published as RFC 6305.

A3: With normal ("forward") queries the domain-name system responds with an address (e.g., "192.0.34.162") when given a name are (e.g., "www.iana.org"). Inverse ("reverse") queries do the reverse – the domain name system returns the name ("www.iana.org") when given the address ("192.0.34.162"). While inverse queries are rare from a human perspective, some network services automatically do an inverse lookup whenever they process a request from a particular IP address, and consequently they form a significant part of DNS network traffic.

Q4: Why do we need the blackhole servers?

A4: Strictly speaking, we don't need the blackhole servers. However, DNS clients will sometimes remember the results from previous queries (that is, "good" answers to queries are cached), and the blackhole servers are configured to return answers that DNS clients can cache. This allows the clients to rely on their cached answers, instead of sending another query, which in turn reduces the overall amount of traffic on the Internet. Since the RFC 1918 addresses should never be used on the public Internet, there should be no names in the public DNS that refer to them. Hence, an inverse lookup on one of these addresses should never work. The blackhole servers respond to these inverse queries, and always return an answer that says, authoritatively, that "this address does not exist". Because of the caching noted above, this is far better than simply not responding at all, so the blackhole servers are provided as a public service.

Q5: How busy are the blackhole servers?

A5: While rates vary, the blackhole servers generally answer thousands of queries per second. In the past couple of years the number of queries to the blackhole servers has increased dramatically. It is believed that the large majority of those queries occur because of "leakage" from intranets that are using the RFC 1918 private addresses. This can happen if the private intranet is internally using services that automatically do reverse queries, and the local DNS resolver needs to go outside the intranet to resolve these names. For well-configured intranets, this shouldn't happen. Users of private address space should have their local DNS configured to provide responses to inverse lookups in the private address space.

Q6: But it looks like the blackhole servers are attacking my network/host. Could it be that a hacker has taken over the servers, and is attacking other systems?

A6: No system is totally safe from hackers, and the blackhole servers are no exception. However, the effect you are seeing very likely has another cause. Because of their special function, there are a number of reasons why the blackhole servers may appear in your logs or elsewhere that have nothing to do with hacking. DNS configuration, especially in an environment where the RFC 1918 addresses are being used, can be tricky. Firewall configurations can make things even more complicated. If, for example, your system is configured to allow all outgoing packets, but to block most incoming packets, then it may be that your DNS client is in fact sending inverse queries to the blackhole servers, but blocking (and logging) the returning answers.

It is also true that other activities of hackers can make the blackhole servers show up in your logs. It is possible to construct network packets with forged source addresses that are in the RFC 1918 ranges. A hacker, for example, could construct a packet that appears to come from 192.168.35.35 and send it to your network. Sometimes there are large-scale denial-of-service attacks that use a flood of such “spoofed” packets. The result might be a large number of queries coming to the blackhole servers, which may themselves be overloaded with query traffic. Under conditions of heavy load, the servers may drop packets, and not respond correctly to some queries. This may cause odd messages to appear in the error logs of either the attacking or the attacked host. (In large scale "distributed denial of service" attacks, many systems are taken over by hackers, and these systems are used to attack some victim. The owners of the attacking systems may not even be aware that they have been taken over by a hacker.)

Q7: OK, maybe you aren't attacking me. What can I do about the messages in my logs?

A7: The best way solve this problem is to set up DNS on your local network. Unfortunately, this can be complicated, and may not in practice be possible. If you are using operating systems from Microsoft, you might want to look at https://support.microsoft.com/en-us/kb/259922. (Please note that the blackhole servers used to be located at isi.edu).

Q8: Is there anything more than just logs at issue?

A8: Possibly. But you should make every effort to fix the problem from your end, because episodes of overload to the blackhole servers are becoming more common, and that can have more serious consequences.

Page content last updated 8 September 2016.

The IANA functions coordinate the Internet’s globally unique identifiers, and are provided by Public Technical Identifiers, an affiliate of ICANN.

Petite Xxx Videos

Porno Young S

Ebnoy Hairy Xxx Foto Gallery

Cekc Rus Xxx

Sex Porno Incest 24

rfc1918 - IETF Tools

Reserved ranges for private IP addresses - IU

IANA — Common questions regarding abuse issues

MAR-10285677-3.v1 | CISA

IPv4Info - IANA netblocks and AS.

What are private IP addresses - RFC 1918 private addresses

10.0.0.119 - Private Network | IP Address Information Lookup

192.168.1.230 - IP Address Information | Whois

IANA IPv4 Special-Purpose Address Registry

Reserved IP addresses - Wikipedia

Private Address Ablk Rfc1918 Iana Reserved