Different Age Sex

👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 ALL INFORMATION CLICK HERE 👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

Intended for healthcare professionals

This site uses cookies. By continuing to browse the site you are agreeing to our use of cookies. Find out more.

You can be signed in via any or all of the methods shown below at the same time.

Sign in here to access free tools such as favourites and alerts, or to access personal subscriptions

If you have access to journal content via a university, library or employer, sign in here

Loading institutional login options...

If you have access to journal content via a university, library or employer, sign in here

Research off-campus without worrying about access issues. Find out about Lean Library here

If you have access to journal via a society or associations, read the instructions below

Access to society journal content varies across our titles.

If you have access to a journal via a society or association membership, please browse to your society journal, select an article to view, and follow the instructions in this box.

Contact us if you experience any difficulty logging in.

Some society journals require you to create a personal profile, then activate your society account

Research off-campus without worrying about access issues. Find out more and recommend Lean Library.

Search all journals

Search this journal

You are adding the following journals to your email alerts

Did you struggle to get access to this article? This product could help you

Accessing resources off campus can be a challenge. Lean Library can solve it

Select style

AMA

APA

Chicago

MLA

Harvard

Share this article via social media.

The e-mail addresses that you supply to use this service will not be used for any other purpose without your consent.

Email a link to the following content:

Sharing links are not available for this article.

For more information view the SAGE Journals Article Sharing page.

Create a link to share a read only version of this article with your colleagues and friends. For more information view the SAGE Journals Sharing page.

Please read and accept the terms and conditions and check the box to generate a sharing link.

I have read and accept the terms and conditions

Age Limits: Men’s and Women’s Youngest and Oldest Considered and Actual Sex Partners

Article first published online: January 25, 2017; Issue published: January 1, 2017

Received: May 05, 2016; Accepted: December 28, 2016

1Department of Psychology, Åbo Akademi University, Turku, Finland

Corresponding Author:

Jan Antfolk, Department of Psychology, Åbo Akademi University, Tehtaankatu 2, 20500 Turku, Finland. Email: jantfolk@abo.fi

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/) which permits non-commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed as specified on the SAGE and Open Access pages (https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/open-access-at-sage).

Whereas women of all ages prefer slightly older sexual partners, men—regardless of their age—have a preference for women in their 20s. Earlier research has suggested that this difference between the sexes’ age preferences is resolved according to women’s preferences. This research has not, however, sufficiently considered that the age range of considered partners might change over the life span. Here we investigated the age limits (youngest and oldest) of considered and actual sex partners in a population-based sample of 2,655 adults (aged 18-50 years). Over the investigated age span, women reported a narrower age range than men and women tended to prefer slightly older men. We also show that men’s age range widens as they get older: While they continue to consider sex with young women, men also consider sex with women their own age or older. Contrary to earlier suggestions, men’s sexual activity thus reflects also their own age range, although their potential interest in younger women is not likely converted into sexual activity. Compared to homosexual men, bisexual and heterosexual men were more unlikely to convert young preferences into actual behavior, supporting female-choice theory.

In several studies men’s and women’s sexual age preferences (i.e., the preferred age of a potential partner) and/or the age of actual sex partners have been investigated. In their seminal paper, Kenrick and Keefe (1992) showed that men’s and women’s sexual age preferences have different developmental trajectories. As a person grows older, the person’s sexual age preferences tend to change, and, as a general rule, the age of desirable partners also increases. The magnitude of this increase differs between the sexes. For women, a year’s increase in her own age is relatively closely matched to a similar increase in the desired partners’ age. Women tend to prefer partners who are similar to or somewhat older than they themselves are (e.g., Kenrick & Keefe, 1992). Men, on the other hand, clearly age faster than their desired partners, and a year’s increase in his own age is accompanied by a smaller increase in the desired partner’s age (e.g., Antfolk et al., 2015). Young men (aged < 20 years) are interested in somewhat older partners than themselves, but as time passes and men age, the interest in partners in their mid-20s is maintained. The result is that older men tend to be interested in women younger than themselves (Antfolk et al., 2015; Kenrick, Gabrielidis, Keefe, & Cornelius, 1996). Generally speaking, earlier studies suggest that heterosexual men—irrespective of their own age—are attracted to women in their 20s and that very few men are exclusively interested in very young or very old women (e.g., Santtila et al., 2015; Tripodi et al., 2015). This pattern has been demonstrated in modern Western and non-Western cultures (Buss, 1989; Buunk, Dijkstra, Kenrick, & Wrantjes, 2001; Sohn, 2016; Souza, Conroy-Beam, & Buss, 2016) and is accompanied by some indirect evidence from hunter-gatherer societies (e.g., Early & Peters, 2000; Marlowe, 2004) and preindustrial societies (e.g., Dribe & Lundh, 2009). Studies have used various measures, including surveys (Antfolk et al., 2015; Buss, 1989; Kenrick et al., 1996), dating advertisements (Dunn, Brinton, & Clark, 2010; Hayes, 1995; Pawlowski & Dunbar, 1999), marriage announcements (Otta, da Silva Queiroz, de Sousa Campos, Dowbor Da Silva, & Telles Silveira, 1999), online chat rooms (Bergen, Antfolk, Jern, Alanko, & Santtila, 2013), and by investigating earnings by prostitutes (Sohn, 2016). In this context, it is also important to separate between studies investigating sexual interest, actual sexual behavior, or age disparity in long-term relationships. Age disparity in long-term relationships is likely a compromise between both women’s and men’s interests (although the relative weight of these two interests likely differ across cultural contexts). This is also true for sexual behavior. Sex, in most cases, necessitates that the sexual interest of two individuals overlap. For example, studies looking at marriage announcements will be informative regarding age disparity in relationships and provide only limited information regarding differences in sexual interest. For example, Buunk, Dijkstra, Kenrick, and Wrantjes (2001) showed that men prefer older partners for short-term versus long-term mating, suggesting that age preferences depend on the amount of involvement. A similar finding was later presented in a study by Young, Critelli, and Keith (2005).

Heterosexual women’s sexual interest in slightly older men has been explained as reflecting the human bi-maturation process, by which females mature earlier than males (van den Berghe, 1992), and/or as a trade-off between the increased social dominance and the decrease in remaining life span in older men (Antfolk et al., 2015). That heterosexual men’s sexual age preferences is focused at women in their 20s has been explained as the evolutionary consequence of this age being associated with high female fecundity and peak copulation to conception ratios (Sozou & Hartshorne, 2012; Tietze, 1957; Wood, 1989). The risk for miscarriages and chromosomal abnormalities in the offspring also becomes approximately 10 times higher in 40-year-old mothers compared to 25-year-old mothers (Hecht & Hook, 1996; Heffner, 2004), and this increase is paired with an increased risk of neuropsychiatric disorders such as autism in offspring (Shelton, Tancredi, & Hertz-Picciotto, 2010).

A female partner’s age is thus associated with men’s probability of producing offspring (and this offspring being healthy), and men who prefer sex with relatively old women would thus have left relatively few allele copies to future generations. To the extent these alleles are associated with sexual age preferences, such preferences would become decreasingly rare in the population (e.g., Kenrick & Keefe, 1992).

What about sexual age preferences in homosexual (vs. heterosexual) men and women? Studies on this topic suggest that age preferences in homosexual individuals are largely similar to those of heterosexual individuals: Like their heterosexual counterparts, homosexual men show a tendency to be sexually interested in young men and homosexual women show a tendency to be interested in women in their own age range (Hayes, 1995; Kenrick, Keefe, Bryan, Barr, & Brown, 1995; Silverthorne & Quinsey, 2000). These findings have been taken to support the modularity hypothesis of sexual orientation. The modularity hypothesis (e.g., Symons, 1979) explains homosexuality as different from heterosexuality only with respect to the sex of the desired partner and suggests that homosexual and heterosexual individuals show similar patterns regarding other aspects of sexual psychology. Thus, no differences in age preferences would be expected based on sexual orientation alone. Very little is known about age preferences in bisexuals. A study by Adam (2000) suggests, however, that both homosexual men and bisexual men display the same interest in young partners as heterosexual men do.

Another, related observation is that both heterosexual men’s and heterosexual women’s actual sexual behavior is predicted by women’s sexual age preferences, and much less by men’s sexual age preferences (Kenrick & Keefe, 1992). This finding has been explained as a function of female choice. Parental investment theory (Trivers, 1972) predicts that women are choosier than men with respect to the characteristics of a potential sexual partner. The reason for this is that women invest more than men in pregnancy, child birth, and nurturing a child and therefore invest more energy in the case of a pregnancy—a very possible consequence of sex (Trivers, 1972). If female choosiness explains the discrepancy between heterosexual men’s preferences and actual behavior, a different pattern ought to emerge in homosexual and heterosexual men. Homosexual men seek to mate mainly with other men, and, if these men are less choosy than women, homosexual men’s sexual interest would more likely be converted into actual behavior. Hence, in the context of sexual interest, no large differences in age preferences is expected, but in the context of sexual behavior, homosexual men are expected to have younger sexual partners compared to heterosexual men.

One limitation in previous research is that scholars have focused on either the most desirable age of partners or a more abstract “mean age preference.” This approach has at least two limitations: it does not appropriately consider the range of an individual’s age preferences, as it assumes that the upper age limit and the lower age limit change similarly over the life span. Neglecting to look at the upper and lower limits separately may therefore bias the results and lead to wrongful conclusions. More specifically, this approach may lead to overlooking the possibility that men’s age preferences widen over the years and that heterosexual men therefore also are sexually interested in the (older) women they tend to have sex with.

In the current study, the aim was to expand on earlier findings on sexual age preferences by investigating the age limits representing the youngest and oldest individuals that men and women could consider having sex with. We expected (i) both women’s youngest and oldest considered sex partners to be strongly and positively associated with their own age. For men, we expected the oldest considered sex partners would be strongly positively associated with their own age, but that the youngest considered partners would show a weaker association with their own age. In other words, we expected men to throughout their life maintain an interest in young women while also becoming interested in older and older women. We also aimed to (ii) replicate the finding that actual sexual behavior in heterosexual men and heterosexual women is more closely predicted by women’s interests compared to men’s interests. Moreover, we aimed to investigate the effects of sexual orientation on age-related sexual interest and sexual activity. In line with previous literature, we expected that (iii) sexual orientation (within one sex) would not be strongly associated with the age of considered partners. As a further test of the female choice theory, we, however, also aimed to test the expectation that (iv) actual sexual behavior would not be as strongly associated with the age of considered partners in heterosexual men as it is in homosexual men. We also explored age preferences in bisexual men and women.

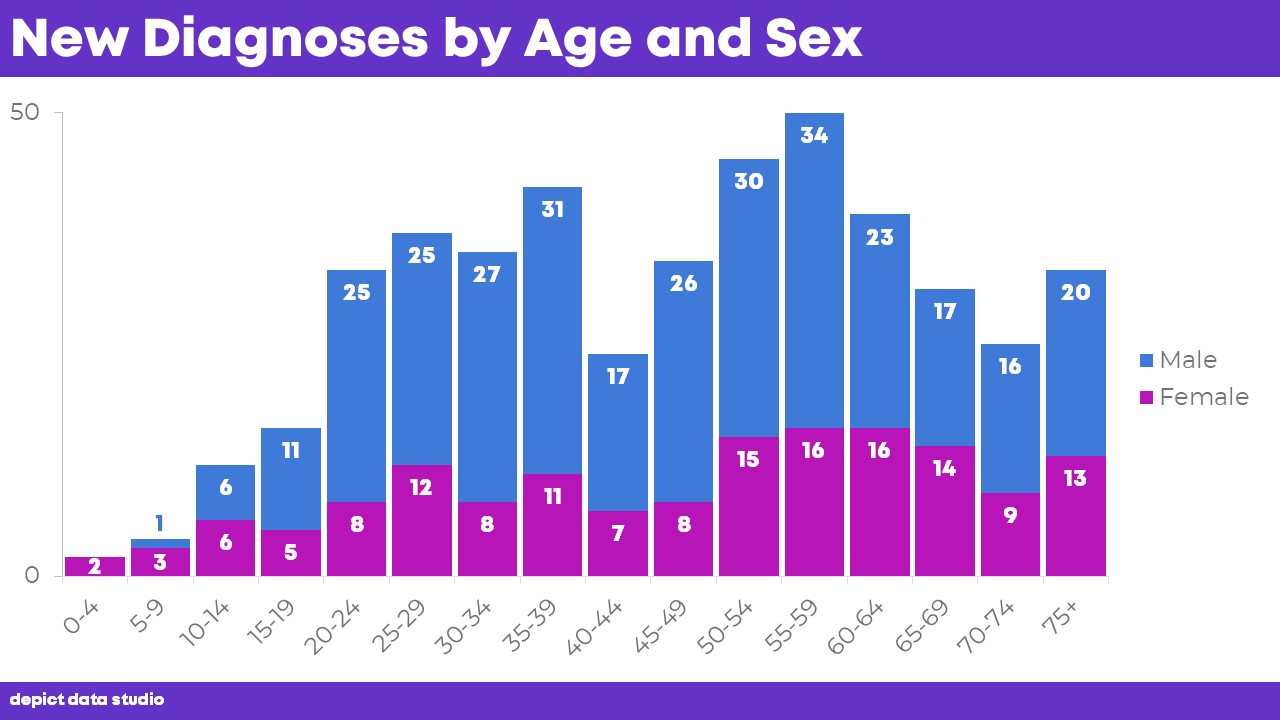

Our final sample included observations from 2,676 individuals. Of these individuals, 878 were male and 1,798 were female. Female participants (M = 33.35, SD = 8.85) were slightly younger than male participants (M = 36.01, SD = 8.46), t(2,674) = 7.40, p < .001. All participants included in the analyses were between 18 and 50 years old (see Figure 3 in Appendix for frequencies of participants across age and sex). Data were obtained from the Finn-Kin data collection (Albrecht et al., 2014), which contains a population-based sample of people living in Finland. This data collection was the result of inviting a randomized sample of individuals aged 18–49 to participate in an online survey of sex and family-related topics. Invitations were sent out, obtaining addresses from the central Population Registry of Finland that keeps information about all individuals residing in Finland. Due to differences in response rates, more women than men participated in the survey. (For more details on this data collection, see Albrecht et al., 2014.)

Participants reported their age using a drop-down menu with answer options between 18 and 99 years of age.

To categorize individuals as homosexual, bisexual, or heterosexual, we summed the responses to two variables measuring sexual behavior with or sexual interest in individuals of the same and opposite sexes. The reason to sum responses across both actual behavior and interest was that behavior is not always the result of interest. By summing variables, both interest and behavior could be considered and given equal weight. Thus, the responses to the two questions “if there was a scale from heterosexual to homosexual, regarding sexual behavior/erotic attraction” where would you place yourself on this scale” were summed. Individuals with the sum value 2 (lowest possible value) were coded as “heterosexual” (n = 1,604). Individuals with values 3 and 4 were coded as “bisexual” (n = 900), and individuals with values above 4 were coded as “homosexual” (n = 171).

The age of the youngest and oldest considered sex partner

Participants reported the age of the youngest and oldest considered sexual partner using a drop-down menu (answer options ranged between 0 and 99) to answer the following questions: “With how young a person could you consider having sex?” and “With how old a person could you consider having sex?”

The age of the youngest and oldest actual sex partner

Participants reported the age of the youngest and oldest sex partner they had during the last 5 years. They used a drop-down menu (answer options ranged between 0 and 99) to answer the following questions: “With how young a person have you had sex during the last 5 years?” and “With how old a person have you had sex during the last 5 years?” (see Appendix for Swedish versions of the questions).

We first expected the variables of interest for possible outliers. Because our data included some extreme values (e.g., observations above 99 or younger than 10 years of age), we removed these observations (3.1%, n = 86) from the data file. We decided to also include young teenagers to capture possible hebephilic interest. Although some observations remained outside the 95% confidence intervals of the mean, we considered it possible that these observations were true observations of the natural variation in age preferences (e.g., young respondents displaying interest in young teenagers or old respondents displaying an interest in older individuals) and chose to keep them in the data file. The very low number of such extreme observations would also not affect our main findings in any major way. We also removed participants who reported being older (0.4%, n = 11) than the actual age limits for the sampling frame (i.e., above 50 years old [50-year-olds were included, because some individuals who was 49 years old at the time of sampling could have turned 50 before responding]). Thus, the original sample size (n = 2,773) was reduced into its current size.

A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) showed that female participants differed in age across the groups of sexual orientation, F(2) = 48.42, p < .001. Also male participants differed in age across groups of sexual orientation, F(2) = 28.81, p < .001. One-way ANOVAs also showed significant differences between groups of sexual orientation in female participants for youngest, F(2) = 88.84, p < .001, and oldest, F(2) = 4.48, p < .05, considered sex partners as well as for youngest, F(2) = 60.27, p < .001, and oldest, F(2) = 21.25, p < .001, sex partners. For male participants, there was a significant difference between the groups of sexual orientation for youngest, F(2) = 15.59, p < .001, but not oldest, F(2) = 2.35, p = .096, considered sex partners. For youngest, F(2) = 32.82, p < .001, and oldest, F(2) = 10.50, p < .001, actual partners, the differences were again significant (Table 1).

Table 1. Mean Age and Standard Deviation of Participant Age and Youngest and Oldest Considered and Actual Partners by Participant Sex and Sexual Orientation.

Table 1. Mean Age and Standard Deviation of Participant Age and Youngest and Oldest Considered and Actual Partners by Participant Sex and Sexual Orientation.

The Association Between Participant Age and the Age of Considered Sex Partners

We then inspected the distribution of data across participant age. This was first done by calcul

Teen Forced Sex Video

Sex Poezde Rus

Kelly Payne Sex Pov

Sinok Jena Ates Sex Porno

Sex Nude Minisuka

Sex-Guide According To Different Age Groups

Age disparity in sexual relationships - Wikipedia

Age Limits: Men’s and Women’s Youngest and Oldest ...

List of countries by age of consent - Wikipedia

Age and Sex Differences in Genetic and Environmental ...

Evaluation and Analysis of Age and Sex Structure

Age-Sex and Population Pyramids - ThoughtCo.com

The amount of sex you should be having according to age ...

Learn the Definition of Age-sex structure | THE-DEFINITION.COM

25 Things Only Couples With Major Age Differences Know ...

Different Age Sex

/afg2-58b9cd145f9b58af5ca7a51f.jpg)